Art Spiegelman’s Maus, the most unconventional great book yet written about the Holocaust, the one that turned Nazis into cats and Jews into mice and Poles into pigs, turns 25 this year. It was the first comic book to win a Pulitzer Prize, and it changed the way comics — the term seems wrong for Maus — are viewed in the US. It proved they could be serious art.

Maus is not a graphic novel but a work of memoir and history. It tells the story of Spiegelman’s father in Poland before World War II, in Auschwitz during the war and as an old coot in Queens, after the fighting stopped. Part of Spiegelman’s accomplishment in Maus is that he turned it into a second-generation Holocaust survivor’s account, too. That is, he made himself a character in the book and threaded in his own quizzical modern sensibility. Maus doesn’t have a tired or sanctimonious bone in its body.

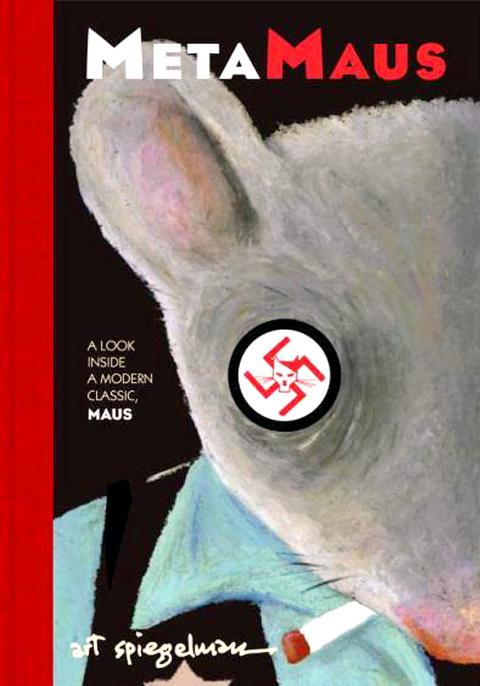

Spiegelman’s new book, MetaMaus, functions as a kind of artist’s scrapbook, chapbook, photo album and storage trunk. Packed with more extras than a new Transformers DVD, it’s a look back at Maus and its complicated composition and reception. His publisher calls this shaggily engaging volume, accurately enough, a “vast Maus midrash.”

An extended interview with Spiegelman fills most of the book’s pages, while arty and inky things pack the margins: draft sketches from Maus, personal photographs, family trees, official documents like his mother’s passport and his parents’ arrest records from Auschwitz.

There’s a DVD included, as well, with an interactive version of Maus and features like interviews and home movies. It’s OK, I suspect, that, as with all such DVDs, few will look at it more than once; then this already-fading technology will become defunct and you will find this swastika-stamped disk at someone’s lawn sale. Let’s talk about the book instead.

The interview with Spiegelman, conducted by Hillary Chute, an English professor at the University of Chicago, is overly long and reverent. But Spiegelman is a witty and testy raconteur, and Chute knows a good deal about comics and she pulls good things from him.

The success of Maus — the first of its two volumes appeared in 1986 — was far from preordained. The book was turned down by many publishers, and Spiegelman prints his rejection letters here, from nearly all of America’s major publishing houses, including Alfred A. Knopf and Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

The idea of a comic book about the Holocaust was inconceivable to most. The idea made people snort. One editor wrote: “You can imagine the response I’ve gotten from the sales department.”

Maus was finally published by Pantheon Books, which gave its author only a small advance.

Maus became a best-seller, surprising Spiegelman as much as anyone else. “I had actually thrived on the relative neglect; it made me get up and work,” he says. “Neurotically, the anhedonic way I experienced the success of Maus was to spend the next 20 years trying to wriggle out from under my own achievement.”

Spiegelman has been a stern critic of what he calls “Holokitsch,” and has been at pains to avoid it. His wife, Francoise Mouly, said to him, “Next to making Maus, your greatest achievement may have been not turning it into a movie.” He knows the sort of life he does not wish to live. “I didn’t want to become the Elie Wiesel of comic books and become the conscience and voice of a second generation.”

The author is instructively apoplectic about the idea that Maus, because it is a comic book, is somehow “Auschwitz for Beginners,” a sugarcoated pill. When the book won a young-adult award from librarians, he was peeved.

“I’d made something as mature as I was capable of making, and it seemed unfair that I was a victim of a prejudice against my medium,” he says. Ultimately, he says, “I reconciled to the fact that if Gulliver’s Travels and Huckleberry Finn can be considered children’s books, I can settle for Maus being on those shelves.”

Still, he reprints one of his own comic strips from The New Yorker, in which he declares, “When parents give Maus,” my book about Auschwitz, to their little kids, I think it’s child abuse.’’

He has complex thoughts about his use of animals to represent Jews, Germans, Poles and others in his book. He notes that Israelis have resisted Maus, uncomfortable that “the image of mice contains the stereotype of Jews as pathetic and defenseless creatures.” Spiegelman convincingly argues that he was using “Hitler’s pejorative attitudes against themselves,” and that using animals “allowed me to approach otherwise unsayable things.”

There is some fetishizing of the artist’s tools in MetaMaus, things like his specially modified Pelikan fountain pens. There are interviews with his wife, son and daughter. They seem like wonderful people, but this material is total filler. More usefully, he reprints transcripts of the often moving interviews he conducted with his father while researching Maus.

Bear in mind that MetaMaus does not contain the actual text of Maus, but it can be read on the DVD. This is not a gift for someone who has not read the original.

Decades after its original publication, Maus continues to provoke. Spiegelman recalls an incident in Germany in 1987, when a reporter barked at him, “Don’t you think that a comic book about the Holocaust is in bad taste?”

He responded: “No, I thought Auschwitz was in bad taste.”

It is a soulful folk song, filled with feeling and history: A love-stricken young man tells God about his hopes and dreams of happiness. Generations of Uighurs, the Turkic ethnic minority in China’s Xinjiang region, have played it at parties and weddings. But today, if they download it, play it or share it online, they risk ending up in prison. Besh pede, a popular Uighur folk ballad, is among dozens of Uighur-language songs that have been deemed “problematic” by Xinjiang authorities, according to a recording of a meeting held by police and other local officials in the historic city of Kashgar in

The Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics (DGBAS) told legislators last week that because the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) are continuing to block next year’s budget from passing, the nation could lose 1.5 percent of its GDP growth next year. According to the DGBAS report, officials presented to the legislature, the 2026 budget proposal includes NT$299.2 billion in funding for new projects and funding increases for various government functions. This funding only becomes available when the legislature approves it. The DGBAS estimates that every NT$10 billion in government money not spent shaves 0.05 percent off

Dec. 29 to Jan. 4 Like the Taoist Baode Temple (保德宮) featured in last week’s column, there’s little at first glance to suggest that Taipei’s Independence Presbyterian Church in Xinbeitou (自立長老會新北投教會) has Indigenous roots. One hint is a small sign on the facade reading “Ketagalan Presbyterian Mission Association” — Ketagalan being an collective term for the Pingpu (plains Indigenous) groups who once inhabited much of northern Taiwan. Inside, a display on the back wall introduces the congregation’s founder Pan Shui-tu (潘水土), a member of the Pingpu settlement of Kipatauw, and provides information about the Ketagalan and their early involvement with Christianity. Most

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) was out in force in the Taiwan Strait this week, threatening Taiwan with live-fire exercises, aircraft incursions and tedious claims to ownership. The reaction to the PRC’s blockade and decapitation strike exercises offer numerous lessons, if only we are willing to be taught. Reading the commentary on PRC behavior is like reading Bible interpretation across a range of Christian denominations: the text is recast to mean what the interpreter wants it to mean. Many PRC believers contended that the drills, obviously scheduled in advance, were aimed at the recent arms offer to Taiwan by the