Half of the Red Hot Chili Peppers are sitting opposite me on a pair of sumptuously plump sofas in a corner suite at the top of a beachfront hotel in Santa Monica, California. Outside the window to my left is the Pacific, while outside the one to my right are the fleshpots and fairgrounds of Venice Beach. It’s 2pm and the sun thumps down in thick, exhausting waves. Even the guy lying flat on his back by the pool, the one with his legs artfully spread so his inner thighs don’t miss out, yanks his towel up in submission and retreats to the tented shade by the bar. On the beach, huge bulldozers roll back and forth endlessly shifting sand, their reverse gear beeps punctuating our every sentence.

Bass player Michael “Flea” Balzary — incredibly, this advert for perpetual adolescence is now 48 — is explaining something about how his love of surfing informs his love of songwriting, and I’m trying to keep up, but his outfit and demeanor aren’t helping me concentrate. Flea has been so enormously famous for so long now that he has successfully slipped all regular behavioral moorings and is gleefully sailing out across his own mental seascape, a blissed-out, UV-grizzled grin worn like a tattered pirate’s flag.

“The apparatus has to serve our improbability and improvisation,” he pronounces, in answer to a question asking how a band formed nearly 30 years ago keep things interesting for themselves on yet another global tour. “Being good and playing the songs is not enough. Being entertaining isn’t enough — I don’t give a shit about that. We must improvise and we must experiment and we must do things that might go wrong and everything we bring — the people and the equipment — must serve us in that goal.”

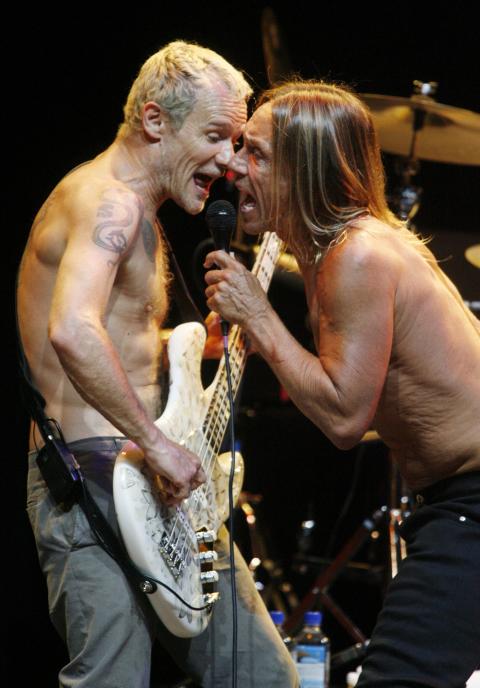

Photo: Reuters

Whatever you might think of Red Hot Chili Peppers, you can’t help but admire someone who has such lofty ideals for their pop group. Especially one dressed in a monogrammed romper-suit the same shade of screechingly psychedelic baby blue that he has dyed his hair.

“Ultimately, whether people like this new record, or us as a band, is irrelevant to me,” says Flea. “But talking about it all is fun.”

On the other sofa, none-more-relaxed drummer Chad Smith, 49, shifts quietly in his seat, a dinner plate-sized luxo-watch hanging off his wrist the only clue to his not-your-regular-Joe status. It is day three of the promotional activity for their new album, I’m With You, and everyone is trying to settle into their proper roles.

I ask Flea and Smith if the record’s title means they are understanding of others, or accompanying them.

“Either way! You can take it anyway you like, sir,” Flea says, thrumming with energy. “I’m going to take it to an air force base and play it in zero gravity.”

“You know, I appreciate Flea a lot in this process,” Smith offers, slowly pulling a bottle of sparkling water from an elaborately carved silver ice bucket. “He’s more articulate, he does a lot of the heavy lifting.”

I’m With You is the Red Hot Chili Peppers’ 10th studio album — quite a feat for a band formed as “a joke,” a one-off prank in Los Angeles in 1983. The record touches on surf music, disco, funk, the 1970s space jazz of George Duke and Herbie Hancock (“I take that as a huge compliment,” Flea says), even the glam-pop of T-Rex (“Oh, now that’s made my day,” singer Anthony Kiedis says later). If you have already decided you can’t stand them, it won’t change your mind, but it does reveal a band that is just as in awe of the possibilities of music as ever. Considering that their history is littered with drug abuse, death and very near death, the Chili Peppers have maintained a level of surprising fecundity: Kiedis and Flea talk of “shitloads” of material no one but them and long-term producer Rick Rubin has ever even heard.

“Creativity waxes and wanes,” Flea says. “We’re very lucky. We’ve made bunches of fucking money. We could be sat on the beach eating burritos, but even when we’re pissed off with each other we sit in a room and work. Igor Stravinsky sat at his piano every fucking day. Some days it was rubbish and his wife was chewing his ear off — but he stuck at it. The same thing goes for Nick Cave, the greatest living songwriter. He goes to work! Every day. And that’s what we do.”

Despite the prosaic way in which Flea describes their current working patterns, there is a lot of dark romance in the story of the Red Hot Chili Peppers. Flea and Kiedis have been friends since early childhood. They’re both the sons of unpredictable, alcoholic fathers (and stepfathers, in Flea’s case). Kiedis wrote at considerable length about his father, the actor Blackie Dammett, in his startling book, Scar Tissue, but Flea’s upbringing was just as chaotic. His violent stepfather was a jazz bassist who, legend has it, would have shoot-outs with the police so regularly that Flea took to sleeping outside for his own safety. By the time he was 12, he would get high and wander the streets at night on his own.

“I was a criminal then,” he nods. “I robbed people.”

The beginnings of the band lie in a hitchhiked journey in a Japanese car. One afternoon 33 years ago, Kiedis and Flea hitchhiked out to a water park in a far distant suburb of LA. After they swam, they smoked a joint, and then realized they couldn’t get home. A few minutes later they spotted a guy driving down the street who was in their geometry class. They waved him down and he gave them a lift in his Datsun B210. They discovered he played guitar in a band; he suggested Flea take up the bass.

“That was Hillel,” Flea says of Hillel Slovak, the band’s original guitarist, who died of a heroin overdose in June 1988. “That one chance occurrence changed our entire lives.”

The band didn’t actually form until 1983, the Kiedis-Flea-Slovak threesome joined by drummer Jack Irons. They played their first gig as Tony Flow and the Miraculously Majestic Masters of Mayhem, gradually winning an audience that made them a more attractive proposition to record labels than Irons and Slovak’s “proper” group, What Is This? Early shows would begin with the welcome, “Good evening, ladies and scumbags!” and might feature a tap dancer who balanced chairs, or a grandmother singing Tie a Yellow Ribbon while making paper dolls. One early review marveled at their “surprising tightness in the face of chaos.”

“That’s still true of us to an extent,” Flea insists. “We were at the dark end of the LA punk scene, and that scene was full-on and violent and aggressive and wild and intense.”

It took some years, in fact, for the Chili Peppers to find their place. They viewed their 1984 debut album as a misfire; its follow-up, Freakey Styley, made no impact on the charts; then, less than a year after 1987’s The Uplift Mofo Party Plan signaled the beginnings of a breakthrough, Slovak died. After a period when it seemed the group would dissolve, they regrouped with John Frusciante replacing Slovak and Smith taking over from Irons at the drums, recording the two albums — Mother’s Milk and Blood Sugar Sex Magick — that drove their ascent to rock aristocracy.

Frusciante, whose tenure in the band was interrupted by problems with heroin addiction through the 1990s (it led to an oral infection so bad he had to have all his teeth removed and replaced with dental implants), left for good in 2009. And so today Kiedis, also 48, is paired with new guitarist Josh Klinghoffer in the suite across the hall from Flea and Smith. I read them an old review that describes a band who would cover themselves with tribal war paint and perform under black light. “Imagine Dr John vocals, Jimi Hendrix fuzztone, George Clinton bass riffs — all delivered with Black Flag venom,” it trills.

“Oh wow, I’ll take that one!” Kiedis smiles, turning the phrase over and over, as if looking for another way in, or another way back. “Black Flag venom! I love that. That’s a glowing review for me.”

Kiedis is a revelation. Softly spoken and discreetly mustached, he allows just enough waspish camp (an aside about David Furnish is hilarious, but entirely unprintable) into his demeanor to completely deflate the macho, tattooed figure he inhabits in the bands photos and videos. When he turns to his new bandmate and asks if, in fact, he’s ever listened to Dr John, he comes across as a kindly uncle, concerned for the cultural life of his young charge. Klinghoffer, who looks more like 21 than the 31 he actually is, nods and snuffles.

“I remember one show when my girlfriend walked on stage in the middle of the set while I was dancing with a naked girl,” Kiedis sighs. “She punched the girl out cold, then threw me down and tried to kick me in the balls. But I would not stop singing. We were playing Foxy Lady and I damn well finished the song!”

Kiedis has the serene poise of someone who has done this for years, unlike Klinghoffer, who never stops moving. A blur of half-smiles, he absentmindedly chews his fingers and tugs at his cuffs. I ask him if it’s intimidating joining such an enormous machine.

“I’ve known the guys for a decade and this is what I’ve wanted to do for my whole life,” he says softly. “Although, if I think about the hugeness of it all, it triggers my anxiety.”

“But you know, when Josh first played with us he walked into a tiny room full of instruments and amps,” Kiedis parries skillfully. “There was no record company or management company. It started off like a simple romance.”

“You know, we never thought about being in a rock ’n’ roll band for ever,” Kiedis says. “We only ever wanted to play one night. Then all the craziness happened. We really did control LA for some time — it was like our own private monarchy.”

The sand-movers are still rolling and beeping as each party gets up to leave. Flea, to no one’s great surprise, hasn’t quite finished talking yet. He’s remembering being seven and thinking about playing music for the first time.

“There was an alley outside my house and these older kids were there with trash can lids and brooms,” he says, zipping up the romper suit and pulling on his boots. “They were pretending they had a band while they mimed to a hidden radio. And I really thought that they were making this music and it seemed like the most amazing magic. And I still feel like that. This is all still completely magical to me.”

‘I’m With You’ is released by Warner on Aug. 29.

Before the recall election drowned out other news, CNN last month became the latest in a long line of media organs to report on abuses of migrant workers in Taiwan’s fishing fleet. After a brief flare of interest, the news media moved on. The migrant worker issues, however, did not. CNN’s stinging title, “Taiwan is held up as a bastion of liberal values. But migrant workers report abuse, injury and death in its fishing industry,” was widely quoted, including by the Fisheries Agency in its response. It obviously hurt. The Fisheries Agency was not slow to convey a classic government

Not long into Mistress Dispeller, a quietly jaw-dropping new documentary from director Elizabeth Lo, the film’s eponymous character lays out her thesis for ridding marriages of troublesome extra lovers. “When someone becomes a mistress,” she says, “it’s because they feel they don’t deserve complete love. She’s the one who needs our help the most.” Wang Zhenxi, a mistress dispeller based in north-central China’s Henan province, is one of a growing number of self-styled professionals who earn a living by intervening in people’s marriages — to “dispel” them of intruders. “I was looking for a love story set in China,” says Lo,

It was on his honeymoon in Kuala Lumpur, looking out of his hotel window at the silvery points of the world’s tallest twin skyscrapers, that Frank decided it was time to become taller. He had recently confessed to his new wife how much his height had bothered him since he was a teenager. As a man dedicated to self-improvement, Frank wanted to take action. He picked up the phone, called a clinic in Turkey that specializes in leg lengthening surgery — and made a booking. “I had a lot of second thoughts — at the end of the day, someone’s going

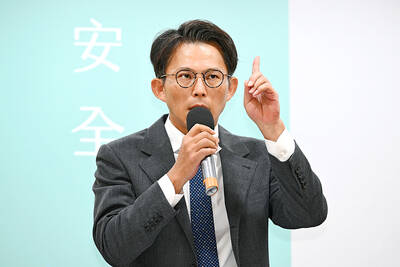

The next few months will be critical in determining the future of the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP). Following party founder Ko Wen-je’s (柯文哲) arrest in September last year, Huang Kuo-chang (黃國昌) effectively became the de facto face of the party and officially became chairman in January. While Ko frequently criticized the ruling Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and insinuated sinister intentions on the part of the DPP’s New Tide faction, his era was largely defined by the TPP slogan “rational, pragmatic, scientific,” albeit defined largely by his definition of what that meant. The tone and language used by the TPP changed dramatically