Jamaica, where Kerry Young was born in 1955, is an island of bewildering mixed bloods and ethnicities. Lebanese, British, Asian, Jewish and aboriginal Taino Indian have all intermarried to form an indecipherable blend of Caribbean peoples. In some ways, this multi-shaded community of nations was a more “modern” society than postwar Britain, where Jamaicans migrated in numbers during the 1950s and 1960s. British calls for racial purity often puzzled these newcomers from the anglophone West Indies, as racial mixing was not new to them. Jamaica remains a nation both parochial and international in its collision of African, Asian and European cultures.

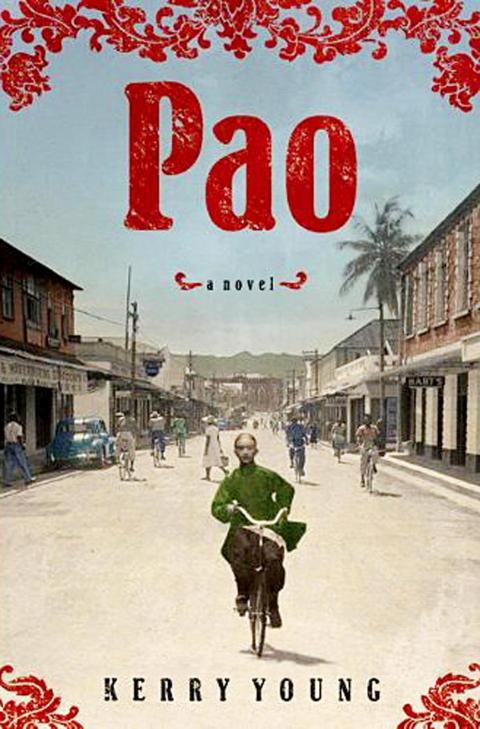

Young, the daughter of a Chinese father and a mother of mixed Chinese African heritage, came to Britain in 1965 at the age of 10. Pao, her zingy first novel, lovingly recreates the Jamaican-Chinese world of her childhood, with its betting parlors, laundries, fortune-telling shops, supermarkets and (business being a hard game in Jamaica) gang warfare. The Chinese first arrived in Jamaica in the 1840s, we learn, as indentured laborers. Having escaped this indignity, they set up business in the Jamaican capital of Kingston selling lychee ice cream, oysters and booby (sea bird) eggs. Racial tensions developed between them and their black neighbors; mixed marriages were generally frowned on. Ian Fleming, in his Jamaican extravaganza Dr No, wrote disapprovingly of the island’s yellow-black “Chigroes.”

Pao, the novel’s eponymous hero, arrives in Jamaica in 1938 a year after the Japanese invasion of China. Emperor Hirohito’s troops have bestially slaughtered some 150,000 Chinese in Nanjing. Terrified, Pao finds sanctuary with a Kingston elder and strongman named Zhang. Like many Jamaican Chinese, Zhang is a Buddhist convert to Catholicism. A razor-sharp tradesman, he owns all the “Chiney shops” and Catholic charities in the vicinity of Chinatown’s Barry Street. The teenage Pao aspires to be like Zhang, but incurs his displeasure one day by consorting in public with a black prostitute called Gloria Campbell. What Pao needs is a nice Chinese girl, Zhang insists, not a black whore.

In time, Pao marries the “socially acceptable” daughter of a Chinese merchant. However, Fay Wong disapproves of her husband as he continues to see Gloria on the sly. The couple fight endlessly. (“She even try to hit me with the bedside lamp but the electric cord stop her short.”) On Zhang’s death, Pao is appointed the most powerful man in Chinatown, with contacts in the Chinese freemason societies known as Tongs. Inevitably, the 21-year-old is involved in shady business, yet he retains a likeably high-spirited charm and humor. (Apparently he is based on the author’s father, Alfred Young, himself a former Chinatown bigwig.)

Along the way, Young provides a micro-history of Jamaica from its independence in 1962 to the present day. In 1965, dreadfully, Chinese properties were set ablaze in Kingston and the owners even “chopped” with machetes. “It was open warfare in the street,” writes Young, as it was believed the Chinese were in business solely to exploit black Jamaicans. Half a century on, the problem of the color line continues to haunt Jamaica. The lighter your complexion, the more privileged you’re likely to be. In pages of patois-inflected prose, Pao celebrates the island’s vibrant ethnic mix-up. Not all Jamaicans are black. Many gradations — Chinese, Indian, Lebanese — can exist within a single family. “They got every shade from blue-black to all sort of brown,” Pao comments, adding: “They even got some with ginger hair.” Eventually he abandons Fay and her wardrobe of silk cheongsams for the Africa-black Gloria.

Poignantly, Pao celebrates a vanished world. Jamaica’s Chinatown disappeared when Kingston railway station closed in the early 1990s. Few Chinese businesses operate there now; the old shops are boarded up or else serve as crack dens. Pao, meanwhile, confirms Young as a gifted new writer. Her novel is a blindingly good read in parts, both for its mesmeric storytelling and the quality of its prose.

June 23 to June 29 After capturing the walled city of Hsinchu on June 22, 1895, the Japanese hoped to quickly push south and seize control of Taiwan’s entire west coast — but their advance was stalled for more than a month. Not only did local Hakka fighters continue to cause them headaches, resistance forces even attempted to retake the city three times. “We had planned to occupy Anping (Tainan) and Takao (Kaohsiung) as soon as possible, but ever since we took Hsinchu, nearby bandits proclaiming to be ‘righteous people’ (義民) have been destroying train tracks and electrical cables, and gathering in villages

Dr. Y. Tony Yang, Associate Dean of Health Policy and Population Science at George Washington University, argued last week in a piece for the Taipei Times about former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) leading a student delegation to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) that, “The real question is not whether Ma’s visit helps or hurts Taiwan — it is why Taiwan lacks a sophisticated, multi-track approach to one of the most complex geopolitical relationships in the world” (“Ma’s Visit, DPP’s Blind Spot,” June 18, page 8). Yang contends that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has a blind spot: “By treating any

This year will go down in the history books. Taiwan faces enormous turmoil and uncertainty in the coming months. Which political parties are in a good position to handle big changes? All of the main parties are beset with challenges. Taking stock, this column examined the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) (“Huang Kuo-chang’s choking the life out of the TPP,” May 28, page 12), the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) (“Challenges amid choppy waters for the DPP,” June 14, page 12) and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) (“KMT struggles to seize opportunities as ‘interesting times’ loom,” June 20, page 11). Times like these can

Swooping low over the banks of a Nile River tributary, an aid flight run by retired American military officers released a stream of food-stuffed sacks over a town emptied by fighting in South Sudan, a country wracked by conflict. Last week’s air drop was the latest in a controversial development — private contracting firms led by former US intelligence officers and military veterans delivering aid to some of the world’s deadliest conflict zones, in operations organized with governments that are combatants in the conflicts. The moves are roiling the global aid community, which warns of a more militarized, politicized and profit-seeking trend