After directing the blockbuster 2003 adventure film Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl and two hit sequels, there was only one movie that Gore Verbinski wanted to make next: an animated feature about a talking chameleon who thinks he’s a western hero. Why? We’re still not entirely sure we understand, but that’s the story behind Rango, which stars Johnny Depp as the voice of the titular lizard, who is liberated from his terrarium and finds himself in a ramshackle frontier town, populated by desert critters (whose voices are provided by Isla Fisher, Ned Beatty, Bill Nighy and many more).

If that premise isn’t sufficiently off the beaten path, Rango is also the first cartoon feature that Verbinski has directed, as well as the first full-length work of animation created by Industrial Light & Magic, the pioneering special-effects film company. Verbinski spoke recently to Dave Itzkoff about why he jumped ship from the Pirates franchise to make Rango, and why he fought back against making the film in 3D. Following are excerpts from that conversation.

Dave Itzkoff: Where did the idea for this film even come from?

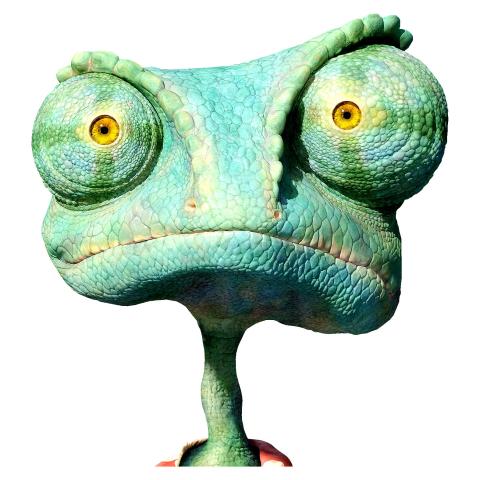

Photo Courtesy of UIP

Gore Verbinski: I was sitting with my good friend David Shannon, who is a children’s book author, and the producer John B. Carls. We were just batting around ideas, like: What do you want to do next? What about an animated western with creatures of the desert? That was basically the sentence. From there, there’s got to be the character who’s an outsider in the classic sense, and if it’s the desert, what if he’s aquatic? If he’s aquatic, what if he’s a chameleon? If he’s a chameleon, then should he be an actor? And I was like, whoa, hey, this is an identity-quest movie.

DI: I don’t think it’s said what kind of lizard Rango is, but he’s definitely a chameleon?

GV: We take great license but, yeah, he’s a chameleon in terms of his ability to change color, but also his ability to perform different roles.

DI: Having never made an animated feature before, how did you then turn this idea into a film?

GV: I wrote a 12-page outline in 2003, and then went off and made two other Pirates movies. So that sat dormant for about four years, and then I looked at my notes and said, “I just want to do this.” I got seven artists in a house, and we just worked for 16 months. It was extremely low-fi: pencil and paper and a Macintosh, a microphone and some guitars. You’d work for six hours, play a game of bocce ball, cook hot dogs on the Weber grill, take walks. It was just fantastic.

DI: You’d just made three lucrative movies for Walt Disney, a company that knows a thing or two about animation. Why didn’t you bring Rango there?

GV: I think their animation pipeline is really full. I think we’d be in queue. It just seemed like, at that time, Paramount was a better fit for us.

DI: What did you show to Paramount to pitch the film, and to Industrial Light & Magic, so the animation could be created?

GV: We could basically play the whole movie to them with temp voices. It was a bunch of pencil drawings, but you got a sense — if you could use your imagination — of the protagonist, his journey, his quest, his exile, epiphany and resurrection. You were looking at pencil and paper, and it was my voice and not Johnny Depp’s. The accurate sketch, just without all the flavor of the entire film.

DI: Was it always a given that Johnny Depp would play the lead character, or did he require some convincing?

GV: We’re pretty good friends, and I think he just had faith. I described it as a lizard project. We had some discussions about it later, and I came back to him with some artwork, and said: “We’re going to do the lizard. Are you going to be ready?” “Yeah, absolutely.” He really committed based on making an animated movie about a lizard.

DI: Instead of recording your voice actors individually in a studio, you produced their dialogue by having them act out their scenes together. Why did you go that route?

GV: I guess fear, really. Fear of a microphone and a cold environment and nobody’s reacting to anybody. We didn’t want a performance that was too clean. If people are running, I want to hear them out of breath in the next line when they stop and talk.

DI: What was that like for the actors?

GV: You show up in dress clothes, there are some props. There’s no lighting, there’s no dolly. You’re doing 10 pages a day. I think that’s very frustrating for actors who are used to doing movies where you do one line, you go back to your trailer for two hours, you come back out and you do another line. At first it’s a shock, and then it’s incredibly liberating.

DI: Was Rango ever planned to be released in 3D?

GV:You could write a book on that one. We went through the whole process. I even presented some tests in 3D. But we had a limited budget, putting all our resources into finishing the film. Any discussion about 3D would have had to be done the right way. I wasn’t going to convert it. So there were battles there, as you can imagine. I was never going to convert this movie.

DI: Are you opposed to 3D films on principle?

GV: I’m not. That doesn’t mean every genre and every period picture, I want to see in 3D. Rango is a film where I could sit down by the fire and tell you the story. It didn’t feel organic.

DI: What do you think about the fact that the next Pirates of the Caribbean movie, which is directed by Rob Marshall, will be released in 3D?

GV: I haven’t seen it. I really look forward to seeing the film. I made three of them. When things stop scaring you, when you’re not sure if you can pull it off or not, it’s time to walk away and find something that truly, you go, “I don’t know how to do this.” Because the education is over. And this has always been a paid education.

DI: At times Rango struck me as a throwback to more adult animated films like Fritz the Cat or Heavy Metal. Do you think audiences are ready to see grown-up stories told through animation again?

GV: I’m dying for the PG-13 animated movies and the R-animated movies. Come on, let’s go. The Ralph Bakshi stuff. Pirates, in a way, was a PG-13 animated movie. It’s very Harryhausen [Ray Harryhausen, the legendary special-effects creator]. But I think that 1970s animation was really fantastic. Imagine what we could do now.

DI: If someone with your track record in Hollywood wants to see these kinds of movies, why can’t they get made?

GV: Data. In a word. There’s no data there. This is a toe in the water. We’re going to get there in small stages. I’m not a numbers guy, but there seem to be a lot of them in our industry.

Most heroes are remembered for the battles they fought. Taiwan’s Black Bat Squadron is remembered for flying into Chinese airspace 838 times between 1953 and 1967, and for the 148 men whose sacrifice bought the intelligence that kept Taiwan secure. Two-thirds of the squadron died carrying out missions most people wouldn’t learn about for another 40 years. The squadron lost 15 aircraft and 148 crew members over those 14 years, making it the deadliest unit in Taiwan’s military history by casualty rate. They flew at night, often at low altitudes, straight into some of the most heavily defended airspace in Asia.

Beijing’s ironic, abusive tantrums aimed at Japan since Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi publicly stated that a Taiwan contingency would be an existential crisis for Japan, have revealed for all the world to see that the People’s Republic of China (PRC) lusts after Okinawa. We all owe Takaichi a debt of thanks for getting the PRC to make that public. The PRC and its netizens, taking their cue from the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), are presenting Okinawa by mirroring the claims about Taiwan. Official PRC propaganda organs began to wax lyrical about Okinawa’s “unsettled status” beginning last month. A Global

Taiwan’s democracy is at risk. Be very alarmed. This is not a drill. The current constitutional crisis progressed slowly, then suddenly. Political tensions, partisan hostility and emotions are all running high right when cool heads and calm negotiation are most needed. Oxford defines brinkmanship as: “The art or practice of pursuing a dangerous policy to the limits of safety before stopping, especially in politics.” It says the term comes from a quote from a 1956 Cold War interview with then-American Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, when he said: ‘The ability to get to the verge without getting into the war is

Like much in the world today, theater has experienced major disruptions over the six years since COVID-19. The pandemic, the war in Ukraine and social media have created a new normal of geopolitical and information uncertainty, and the performing arts are not immune to these effects. “Ten years ago people wanted to come to the theater to engage with important issues, but now the Internet allows them to engage with those issues powerfully and immediately,” said Faith Tan, programming director of the Esplanade in Singapore, speaking last week in Japan. “One reaction to unpredictability has been a renewed emphasis on