It’s plentiful, portable, durable, and so simple that even a child can use one. It’s the Avtomat Kalashnikova, or AK-47, the assault rifle that Josef Stalin gave to the world and that long outlived the Cold War.

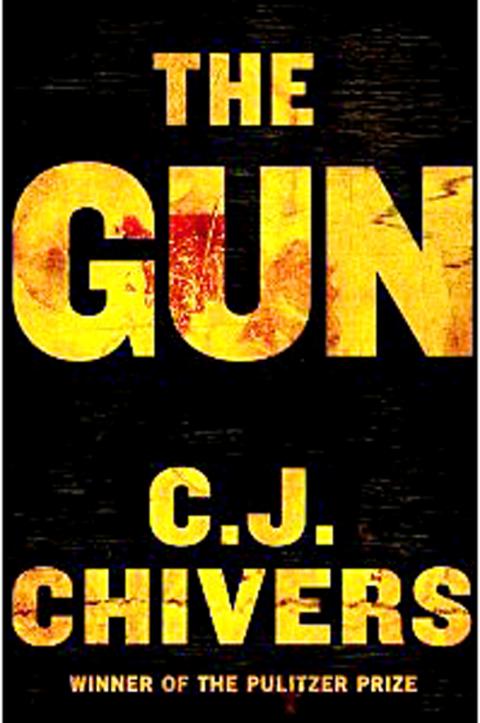

Named for the man credited with its invention, Mikhail Kalashnikov, and the year the Soviet Union adopted it, 1947, the AK-47 is an in-between weapon — lighter and shorter than previous infantry rifles yet more accurate and powerful than a submachine gun. C.J. Chivers, in his exhaustive and bleak history The Gun, concludes that the weapon will have a strong influence on armed conflict for decades to come.

The AK-47 had fewer moving parts than typical automatic rifles, and those parts were loose-fitting and massive, making a dirty gun less likely to jam. The Soviets gave these durable machines to just about anyone who might advance their goals, and even helped their neighbors — including China — build their own AK factories. The world is awash in AKs and their progeny.

“These weapons began as a means to equip standing armies,” Chivers writes. “But the nations that made them lost custody of them, and then control, and now in much of the world they are everyman’s gun.”

Small arms were the weapon of choice in 46 of 49 major conflicts in the 1990s, in which 4 million people died, Chivers says, citing a UN report. AKs and AK knockoffs were the primary rifles used.

Flags and vodka

Today they appear on flags and as props in terrorist videos. US Marines practice breaking down and reassembling them, “just in case.” There’s even a Kalashnikov vodka.

Chivers, a New York Times senior writer who served in the Marine Corps in the Gulf War, combines a soldier’s experience with an historian’s skepticism. You probably won’t be able to trade a chicken for an AK, as is sometimes asserted, he says; one can be had for a few head of cattle. More tellingly, he shows how the price of an AK is a barometer of how dangerous a place has become.

His tale starts in the 1860s with inventor and businessman Richard Gatling and proceeds to Hiram Maxim, the sadist and possible trigamist, Chivers says, who developed one of the first viable automatic weapons.

When you fire a rifle, it recoils and releases a burst of gas. Automatic weapons harness that wasted energy to eject the spent cartridge and push back a bolt. The bolt then bounces off a spring and smashes into the next cartridge, setting the process in motion again. After Maxim, automatics grew smaller and deadlier, culminating in the abattoir that was World War I.

Creature of propaganda

The life of Kalashnikov himself is obscured in Soviet secrecy and mendacity. He may have been the resourceful tinkerer of popular myth. Yet according to Chivers he was also the willing creature of a propaganda machine that gave him more credit than he deserved for the work of many hands.

Kalashnikov, who celebrated his 90th birthday in November last year, seeks credit when his gun is put to uses he likes — such as defending the motherland — and disavows responsibility for the destruction it causes elsewhere.

“I have always tried to knock down that annoying stereotype: if you are a weapons designer, you are a murderer,” Chivers quotes him as saying.

Chivers contrasts the AK with the American-made M16, which he says was issued to US troops in Vietnam before it was ready for jungle duty. It corroded and jammed, sometimes with fatal consequences. Some soldiers would abandon their M16s in favor of captured AKs. Though the American weapon has since been improved, the damage was done.

The greatest strength of The Gun lies in the stories told by rank-and-file gunfighters. Chivers devotes space to child soldiers in Uganda, Marines in Southeast Asia and Kurdish bodyguards in northern Iraq. One by one, they describe what it’s like to shoot, and be shot by, this killing machine, a device that can unload hundreds of bullets in a minute.

This year will go down in the history books. Taiwan faces enormous turmoil and uncertainty in the coming months. Which political parties are in a good position to handle big changes? All of the main parties are beset with challenges. Taking stock, this column examined the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) (“Huang Kuo-chang’s choking the life out of the TPP,” May 28, page 12), the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) (“Challenges amid choppy waters for the DPP,” June 14, page 12) and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) (“KMT struggles to seize opportunities as ‘interesting times’ loom,” June 20, page 11). Times like these can

June 23 to June 29 After capturing the walled city of Hsinchu on June 22, 1895, the Japanese hoped to quickly push south and seize control of Taiwan’s entire west coast — but their advance was stalled for more than a month. Not only did local Hakka fighters continue to cause them headaches, resistance forces even attempted to retake the city three times. “We had planned to occupy Anping (Tainan) and Takao (Kaohsiung) as soon as possible, but ever since we took Hsinchu, nearby bandits proclaiming to be ‘righteous people’ (義民) have been destroying train tracks and electrical cables, and gathering in villages

Dr. Y. Tony Yang, Associate Dean of Health Policy and Population Science at George Washington University, argued last week in a piece for the Taipei Times about former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) leading a student delegation to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) that, “The real question is not whether Ma’s visit helps or hurts Taiwan — it is why Taiwan lacks a sophisticated, multi-track approach to one of the most complex geopolitical relationships in the world” (“Ma’s Visit, DPP’s Blind Spot,” June 18, page 8). Yang contends that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has a blind spot: “By treating any

Swooping low over the banks of a Nile River tributary, an aid flight run by retired American military officers released a stream of food-stuffed sacks over a town emptied by fighting in South Sudan, a country wracked by conflict. Last week’s air drop was the latest in a controversial development — private contracting firms led by former US intelligence officers and military veterans delivering aid to some of the world’s deadliest conflict zones, in operations organized with governments that are combatants in the conflicts. The moves are roiling the global aid community, which warns of a more militarized, politicized and profit-seeking trend