A fter sharing directorial credits with Lawrence Lau (劉國昌) for last year’s City Without Baseball (無野之城), a movie about Hong Kong’s only amateur baseball team that featured a fair amount of full frontal nudity, Scud (雲翔) returns with Permanent Residence (永久居留). The semi-autobiographical movie traces the life of its protagonist from his birth in the 1960s to his death some 80 years later and deals with homosexual awakening, unrequited love and musings on life and death.

It is an honest and affected gay drama, but the film’s unbridled self-indulgence may be its undoing.

Ivan (Sean Li, 李家濠) is an IT professional who works hard and has no time for dating. The young man is forced to come face-to-face with his sexuality when Josh (Jackie Chow, 周德邦) from Israel asks if he is gay during a television talk show in which the two are guest speakers and a life-long friendship begins.

After entering the gay world, Ivan meets Windson (Osman Hung, 洪智傑), who professes to be straight. A curious friendship blossoms between the two involving many episodes of nude wrestling, swimming, embracing and sharing a bed. Though apparently attracted to the free-spirited Ivan, Windson insists on limiting their relationship to nothing more than kisses and fondling.

When Windson announces he plans to wed his long-time girlfriend, Ivan is devastated and sets off on a journey of discovery that takes him from Israel to Thailand to Australia and finally back to Hong Kong.

Permanent Residence is flamboyantly out. With the bodies of avid gym-goers, both leads take delight in celebrating their naked, muscular flesh for the audience’s viewing pleasure. They drop their towels and fly kick for no apparent reason, frolic on the beach, skinny-dip in the ocean, hold hands and share their secrets and longings in what feels like a homoerotic utopia.

The gay never-never land is effectively contrasted with the confining world of social norms that force Windson to stay with a woman who expects wedded bliss. The familiar torments of coming out will strike a chord with many Asian audience members.

Its honest, well-intended portrait of gay/straight relationships is the film’s only saving grace. Alternating between homoerotica and existential contemplations on life and death, the film is stylistically inconsistent, which shows that director Scud still has a lot to learn.

Permanent Residence tries to blend together too many subjects — love, relationships, identity and family — but none of them is fully explored. The movie flits from China to Japan, Israel to Thailand, to Australia, but instead of conveying philosophical undertones, the backdrops merely serve the purpose of vain embellishment and are superfluous.

The unexpected coda exudes a sci-fi, futuristic charm and provides entertainment value with its artlessness and stylistic oddity.

What is a real turn-off, however, is the unbridled narcissism acutely felt throughout the movie. Filmmakers often mine their personal experiences, but in this case the results are overbearing.

Ivan lives his childhood years in China and becomes an IT success in Hong Kong. Same with Scud. Ivan moves to Australia and returns to Hong Kong to make a baseball movie. Ditto Scud. Egocentric in the extreme, Permanent Residence contains many moments of self-promotion, including a scene in which Ivan’s brother urges him to reproduce because he’s just too talented not to pass on his genes.

Final verdict: the former IT whiz kid-turned-director may live an interesting life and have lots of stories to tell. But before Scud can make his own 8 1/2, he needs to master self-restraint.

The Nuremberg trials have inspired filmmakers before, from Stanley Kramer’s 1961 drama to the 2000 television miniseries with Alec Baldwin and Brian Cox. But for the latest take, Nuremberg, writer-director James Vanderbilt focuses on a lesser-known figure: The US Army psychiatrist Douglas Kelley, who after the war was assigned to supervise and evaluate captured Nazi leaders to ensure they were fit for trial (and also keep them alive). But his is a name that had been largely forgotten: He wasn’t even a character in the miniseries. Kelley, portrayed in the film by Rami Malek, was an ambitious sort who saw in

Last week gave us the droll little comedy of People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) consul general in Osaka posting a threat on X in response to Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi saying to the Diet that a Chinese attack on Taiwan may be an “existential threat” to Japan. That would allow Japanese Self Defence Forces to respond militarily. The PRC representative then said that if a “filthy neck sticks itself in uninvited, we will cut it off without a moment’s hesitation. Are you prepared for that?” This was widely, and probably deliberately, construed as a threat to behead Takaichi, though it

Among the Nazis who were prosecuted during the Nuremberg trials in 1945 and 1946 was Hitler’s second-in-command, Hermann Goring. Less widely known, though, is the involvement of the US psychiatrist Douglas Kelley, who spent more than 80 hours interviewing and assessing Goring and 21 other Nazi officials prior to the trials. As described in Jack El-Hai’s 2013 book The Nazi and the Psychiatrist, Kelley was charmed by Goring but also haunted by his own conclusion that the Nazis’ atrocities were not specific to that time and place or to those people: they could in fact happen anywhere. He was ultimately

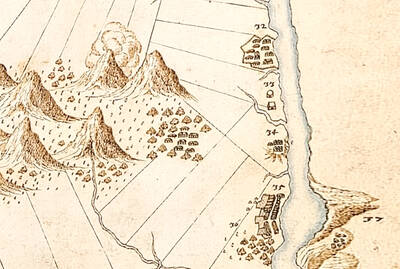

Nov. 17 to Nov. 23 When Kanori Ino surveyed Taipei’s Indigenous settlements in 1896, he found a culture that was fading. Although there was still a “clear line of distinction” between the Ketagalan people and the neighboring Han settlers that had been arriving over the previous 200 years, the former had largely adopted the customs and language of the latter. “Fortunately, some elders still remember their past customs and language. But if we do not hurry and record them now, future researchers will have nothing left but to weep amid the ruins of Indigenous settlements,” he wrote in the Journal of