I’m perched on the end of a longtail boat, cocktail in hand, head to the wind. The silhouettes of thousands of people line the length of the beach in front of me, and a throbbing bass reverberates in my chest. Just two minutes ago, I was in the middle of that neon-clad throng, dancing full-moon-style with the best of them. And now here I am, making my James Bond-style getaway to quieter shores up the coast. If only I could leave every party in this way.

Unlike its neighbor Koh Samui, the mountainous island of Koh Phangan in southern Thailand has no airport and only a small number of roads. Its terrain has saved it from large-scale development, and much of the island is only accessible by boat. Aside from the mainstream commerciality of Hat Rin, near-deserted beaches and pockets of solitude abound.

In fact, the further up the coast you go, the quieter life becomes. Huge limestone rocks frame the bays, and dense forest rises up the hillside behind. At this time of year — June to September, before the monsoon comes knocking — it’s the islands on the eastern side of the peninsula that remain drier and sunnier.

As we round the headland and point our boat towards the next bay, my shoulders relax. The atmosphere has changed drastically, and in place of the craziness of Hat Rin, a more peaceful scene comes into view — the calm after the party storm.

By the light of the full moon, I can just make out wooden huts standing precariously on the rocks. People sit around bonfires on the beach, and the pace of life drops about 20 notches. This is what I love about Koh Phangan. Within a 6.4km radius two different worlds exist. As the Thais say, “Same, same, but different.”

I discovered this particular stretch of coastline after a two-month spell in Nepal. I’d pushed my body to its limits trekking around the Annapurna circuit and contracted a particularly nasty and resilient stomach parasite in the process. A girl I met in Kathmandu told me that to stand any chance of getting well again, I should hop on the next flight to Thailand and get myself to Koh Phangan, pronto.

One plane ride, a night bus, a catamaran, two taxis and a longtail boat later, and I arrived at the Sanctuary resort. Tucked into a corner of Hat Thian beach, it is the kind of place you book into for a week and end up staying for a month.

Here, among the thatched roofs, decks and balconies above a translucent Gulf of Thailand, health and well-being is a laid-back, low-key affair. The antithesis of a clinical five-star spa, nobody’s going to come at you with a white coat and a clipboard and, depending on your inclination and budget, you can do as much or as little as you like. You can detox or retox, stay in a dorm for NT$115 per night or a NT$5,200-a-night air-conditioned chalet.

As well as the large tree-house-style restaurant, the Sanctuary has a small shop, a spa offering Balinese body wraps and pineapple scrubs, a plunge pool and a herbal steam room built into the rocks. Incense floats on the breeze and people drift between yoga and meditation classes or laze around in hammocks sipping fresh fruit smoothies.

If you have to up the ante — to add some oomph to your Om — there’s elephant trekking, jet-skiing and cooking classes, along with diving and snorkeling in the Ang Thong marine national park. Many of the Sanctuary’s guests drift in and out of the retreat, interspersing its serenity with the buzz of Hat Rin or less commercial local bars nearby.

Some come just for the yoga, which is held three times a day in a large hall in the jungle, others to gorge on seafood or healthy veggie dishes, tucking into the likes of Thai spinach salad with peanut coconut sauce, or pad pak sai met ma muang (stir fried vegetables with cashew nuts and chilli).

Give it time to settle and there’s kayaking, snorkeling and hikes up to the lookout, not to mention a well-stocked library and workshops on every complementary therapy under the sun. They’re balm for the party animals, who slip away from the Sanctuary to cane it under a full moon before returning for rest and recovery.

To one side, in its own enclave, is the wellness center — a separate home for the cleansing programs. Run by a man called Moon, for whom fasting is a way of life, the detoxes range from one to seven days, with milder juice fasts and specific liver-cleansing regimes.

I opt for the three-day cleanse, feeling a little nervous about its psychological and physical effects. Moon tells me to eat nothing but raw fruit and vegetables for two days in order to prepare my body. After that only coconut, clay and psyllium juice will pass my lips during the fast.

Considering the Sanctuary serves some of the best vegetarian food this side of California, it feels sadistic in the extreme. Moon tells me my body will thank me when it’s all over, while I remind myself that Dolly Parton wrote some of her best songs while fasting. So maybe some good will come of it.

I cast a wistful glance in the direction of the cake cabinet and sulk off to my salad. The cleanse is not for the fainthearted, and it’s a good idea to eat healthily beforehand and get in the right frame of mind, but I was amazed how good I felt after.

Back on solids, and the days pass in a haze of extended mealtimes, chats about life, and swims in the ocean. I make the most of the morning yoga, experience one of the best massages of my life, and leave feeling stronger, happier and more relaxed than I have in a long time.

As well as the Sanctuary, there are a number of smaller-scale resorts, both in Hat Thian and Hat Yuan, that serve phenomenal Thai and Western food. Most also have cheap beach huts to rent. My favorite is the Bamboo Hut, an open-air restaurant with a smattering of bungalows perched on top of the rocks between the beaches. It does a mind-blowing tofu cheeseburger and the best chocolate coconut muffin you’ll ever taste. Fasters need not apply.

Last week the story of the giant illegal crater dug in Kaohsiung’s Meinong District (美濃) emerged into the public consciousness. The site was used for sand and gravel extraction, and then filled with construction waste. Locals referred to it sardonically as the “Meinong Grand Canyon,” according to media reports, because it was 2 hectares in length and 10 meters deep. The land involved included both state-owned and local farm land. Local media said that the site had generated NT$300 million in profits, against fines of a few million and the loss of some excavators. OFFICIAL CORRUPTION? The site had been seized

Next week, candidates will officially register to run for chair of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). By the end of Friday, we will know who has registered for the Oct. 18 election. The number of declared candidates has been fluctuating daily. Some candidates registering may be disqualified, so the final list may be in flux for weeks. The list of likely candidates ranges from deep blue to deeper blue to deepest blue, bordering on red (pro-Chinese Communist Party, CCP). Unless current Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) can be convinced to run for re-election, the party looks likely to shift towards more hardline

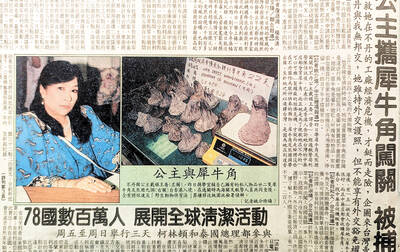

Sept. 15 to Sept. 21 A Bhutanese princess caught at Taoyuan Airport with 22 rhino horns — worth about NT$31 million today — might have been just another curious front-page story. But the Sept. 17, 1993 incident came at a sensitive moment. Taiwan, dubbed “Die-wan” by the British conservationist group Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), was under international fire for being a major hub for rhino horn. Just 10 days earlier, US secretary of the interior Bruce Babbitt had recommended sanctions against Taiwan for its “failure to end its participation in rhinoceros horn trade.” Even though Taiwan had restricted imports since 1985 and enacted

The depressing numbers continue to pile up, like casualty lists after a lost battle. This week, after the government announced the 19th straight month of population decline, the Ministry of the Interior said that Taiwan is expected to lose 6.67 million workers in two waves of retirement over the next 15 years. According to the Ministry of Labor (MOL), Taiwan has a workforce of 11.6 million (as of July). The over-15 population was 20.244 million last year. EARLY RETIREMENT Early retirement is going to make these waves a tsunami. According to the Directorate General of Budget Accounting and Statistics (DGBAS), the