Researchers have scooped soil near the Quabbin Reservoir in Massachusetts, visited a Russian volcano, and scoured the bottom of the sea looking for microbes that hold the key to new biofuels. Now, they are investigating deeper into the belly of termites.

The otherwise dreaded insect is a model bug bioreactor, adept at the difficult task of breaking down wood and turning it into fuel. Learning the secret of that skill could open the door to creating a new class of plant-based fuels to offset reliance on petroleum products. What scientists have learned so far, however, suggests it won’t be easy to duplicate nature.

Over the past year, several studies elucidating termite innards have appeared in mainstream science journals. And last month, Japanese researchers added their own report on just how termites digest wood. A key, they said, can be found within termites’ bodies like nested Russian dolls — a bacteria that lives within a microorganism that lives within the termite gut.

It’s an intriguing, and complicated, symbiosis.

“We only need to look to nature to get a clear sign this is not going to have a simple solution,” said Jared Leadbetter, associate professor of environmental microbiology at the California Institute of Technology, who was not involved in the study. “With 100 million years-plus to streamline this process, you have species living within species, living within species. So we better embrace the fact this is going to have a complex answer.”

In a study published last year, Leadbetter and others explored a small sample of termite gut bacteria genes, and found 1,000 involved in breaking down wood.

The new study, which focuses on one of the most voracious of the 2,600 termite species, illustrates yet more complexity. The work, published in the journal Science, shows how a partnership within termite guts helps explain wood digestion.

The microorganism, called P. grassi, breaks down cellulose, a component of wood. A bacteria that lives inside that microorganism provides nitrogen, necessary for life, but scarce in wood. Researchers have sequenced the genes of the bacteria and some of the protozoa, and are now analyzing the ones involved in digesting cellulose — in hopes of better understanding the secrets of the digestion process.

“As a team, we are aiming to find out factors useful for making a novel biofuel,” author Yuichi Hongoh, of the Ecomolecular Biorecycling Science Research Team at RIKEN, a research institute in Wako, Japan, wrote in

an e-mail.

The challenge of making fuel from rigid plants, such as trees, is that they lock away energy in complex molecules.

“Cellulose is a very, very tough molecule. You can hit it with acid ... and it will just sit there,” said Alexander DiIorio, director of the bioprocess center at Worcester Polytechnic Institute. He is looking at everything from termites to rotting wood in the search for ways to make cellulosic ethanol. His work is funded by California biofuels company Eden IQ.

Adding to the difficulty is that a rigid material called lignin is woven in with the cellulose. Researchers are looking for a variety of solutions to these problems — and in another scourge-turned-science moment, Pennsylvania State University researchers reported this summer that a fungus harbored in the gut of the Asian Longhorned Beetle that is ravaging Worcester’s maples could help degrade lignin.

But even when promising enzymes and microbes have been identified, the work isn’t straightforward.

For example, a microbe discovered

in a soil sample from the Quabbin

Reservoir can convert woody plant matter directly into ethanol, according to Sue Leschine, a professor of microbiology at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. But Qteros, the company she cofounded to work on the microbe, is untangling problems such as how to more cheaply prepare the raw materials for microbe digestion, and speed up the process.

Still, entrepreneurs are moving forward. Mascoma Corp, a cellulosic ethanol company based in Boston, announced in October that it had raised US$49.5 million toward building a plant in Michigan.

Verenium Corp in Cambridge, Massachusetts built a demonstration plant in Louisiana and is working to extract fuel from materials like bagasse — the remnants of sugar cane. Verenium, like other companies, is interested in termite innards, but ultimately is taking a much broader approach — scanning the great microbiological diversity of the world.

“Academics want to unravel [termite digestion] so they can get down to the first principles of what makes it work,” Gregory Powers, executive vice president at Verenium said. “Our feeling is that process takes a very, very long time to elucidate … We’re in a business to sell chemicals, so we can’t wait for the big research breakthrough in one or five years.”

But to see the biofuel problem as a matter of scientific breakthroughs is itself misleading, Leadbetter said, considering the challenges posed by logistical issues such as building plants, distribution networks, and a supply chain of biomass.

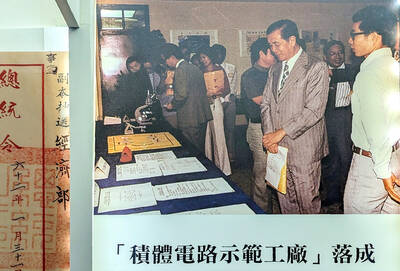

Oct. 27 to Nov. 2 Over a breakfast of soymilk and fried dough costing less than NT$400, seven officials and engineers agreed on a NT$400 million plan — unaware that it would mark the beginning of Taiwan’s semiconductor empire. It was a cold February morning in 1974. Gathered at the unassuming shop were Economics minister Sun Yun-hsuan (孫運璿), director-general of Transportation and Communications Kao Yu-shu (高玉樹), Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI) president Wang Chao-chen (王兆振), Telecommunications Laboratories director Kang Pao-huang (康寶煌), Executive Yuan secretary-general Fei Hua (費驊), director-general of Telecommunications Fang Hsien-chi (方賢齊) and Radio Corporation of America (RCA) Laboratories director Pan

The consensus on the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) chair race is that Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) ran a populist, ideological back-to-basics campaign and soundly defeated former Taipei mayor Hau Lung-bin (郝龍斌), the candidate backed by the big institutional players. Cheng tapped into a wave of popular enthusiasm within the KMT, while the institutional players’ get-out-the-vote abilities fell flat, suggesting their power has weakened significantly. Yet, a closer look at the race paints a more complicated picture, raising questions about some analysts’ conclusions, including my own. TURNOUT Here is a surprising statistic: Turnout was 130,678, or 39.46 percent of the 331,145 eligible party

The classic warmth of a good old-fashioned izakaya beckons you in, all cozy nooks and dark wood finishes, as tables order a third round and waiters sling tapas-sized bites and assorted — sometimes unidentifiable — skewered meats. But there’s a romantic hush about this Ximending (西門町) hotspot, with cocktails savored, plating elegant and never rushed and daters and diners lit by candlelight and chandelier. Each chair is mismatched and the assorted tables appear to be the fanciest picks from a nearby flea market. A naked sewing mannequin stands in a dimly lit corner, adorned with antique mirrors and draped foliage

The election of Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) as chair of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) marked a triumphant return of pride in the “Chinese” in the party name. Cheng wants Taiwanese to be proud to call themselves Chinese again. The unambiguous winner was a return to the KMT ideology that formed in the early 2000s under then chairman Lien Chan (連戰) and president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) put into practice as far as he could, until ultimately thwarted by hundreds of thousands of protestors thronging the streets in what became known as the Sunflower movement in 2014. Cheng is an unambiguous Chinese ethnonationalist,