In 1962, in a studio overlooking Campo de’ Fiori in Rome, the city he had moved to in 1957 from the US and which he still regards as his home, Cy Twombly made a painting that could have been construed as a calculated affront to — even a philistine rejection of — la Citta Eterna with its magical light and fountains and churches, and all the ruins of classical civilizations.

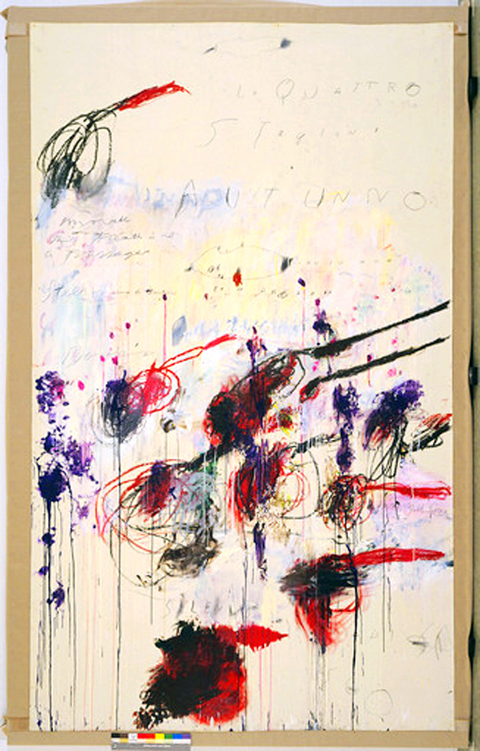

Twombly’s practice in those years was to cover the whole of a large room with canvas and then start working close to the floor or up under the ceiling, wherever his eye took him. When many days had passed and all the walls were smeared with smudges of paint and fecal-looking stains and spidery unravellings of graffiti, he would hack off a section that looked as if it might have the makings of a painting and nail it to the wall without a stretcher.

Untitled of 1962 was typical of the work coming out of his studio during this time: with its spurts and scrawls and gougings and deeply incised, nearly legible scribbles (the New Yorker critic Peter Schjeldahl once described the mess of Twombly marks as being like what a dog does when it’s getting ready to lie down), it looked like a panel from a particularly unruly public convenience. Or, as an Italian reviewer remarked at the time, like the proliferating graffiti on the scarred marble of Rome’s walls and monuments.

PHOTO COURTESY OF THOMAS AMMANN FINE ART, ZURICH AND CY TWOMBLY

“His is an act of desecration, vandalization, of bringing the language of abstract expressionism out of the realm of personal expression and into the world of writing and language,” the American critic and great Twombly champion, Kirk Varnedoe, wrote of the 1962 painting. (Twombly needed a champion in America for a 25-year period, beginning in the mid-60s, when his Europhile and old-world painterly tendencies combined to keep him out of fashion.) “Everything about its gushiness, its expression,” Varnedoe continued, “is filtered again through the idea of defacement and negation. This is not the cool, beautiful continuity of abstract expressionism, but a rather jerky, hesitant, intermittent negotiation of a set of signs.”

The signs in question were ones that would be familiar to any playground doodler or rest-room dawdler: gash-like orifices, rampant phalluses, rude, cartoon-like ejaculations of paint. Rosalind Krauss has written about the “crude violence” and the “obsessional formulation of bodily parts” that characterized Twombly’s paintings of the early 1960s.

Twombly first visited Rome in the company of Robert Rauschenberg during an eight-month tour of north Africa and Europe between 1952 to 1953. They had met at the Art Students League in New York and had attended the progressive Black Mountain College in North Carolina together in the summer of 1952, where their teachers had included Franz Kline and the poet Charles Olson, as well as Rauschenberg’s future friend and long-term collaborator, John Cage.

PHOTO COURTESY OF THOMAS AMMANN FINE ART, ZURICH AND CY TWOMBLY

When Twombly returned to Rome in 1957, he returned alone, and moved into a large studio with views of the Colosseum. Coincidentally living in Rome at the same time, in a draughty palazzo off the Piazza Venezia with his young family, was a writer who, although nearly a generation older than Twombly (who was born in 1928), seems to have shared his outlook and preoccupations, and even his temperament, to a marked degree.

It is unclear whether John Cheever and Twombly ever met during Cheever’s 12-month sojourn in Rome. Twombly crops up in Rachel Cohen’s book A Chance Meeting: Intertwined Lives of American Writers and Artists, but it is in the context of Cage and the choreographer Merce Cunningham and their bohemian downtown New York crowd. Cheever, the so-called “Chekhov of the suburbs,” mixed in different circles: for decades, the locus of his fiction remained the drawing rooms, swimming pools, churches, clubhouses and beaches of the Hudson Valley he had moved into with his wife and children in the early 1950s. Cheever was never wealthy. But (like Twombly) he had a naturally patrician manner that suggested breeding and money, and a notion of him as part of the country squirearchy — a kind of laminated placemat figure complete with hunting dogs, wooded estate, staff and saddle horses — took root. (Cheever’s father had been a prosperous shoe manufacturer who lost his fortune in the stock-market crash of 1929; Twombly’s father was a former pitcher for the Chicago White Sox, a former pro golfer and, in later years, the head of the athletic department at a small college.)

“Oh this big, wild, rowdy country, full of whores and prize-fighters, and here I am stuck with an old river in the twilight and the deterioration of the middle-aged businessman,” Cheever lamented in 1953, as recorded in his posthumously published Journals. “While all my friends are describing orgasms, I still dwell on the beauty of the evening star.”

PHOTO COURTESY OF THOMAS AMMANN FINE ART, ZURICH AND CY TWOMBLY

The catalogue that accompanies Twombly’s new show at Tate Modern — a kind of selective retrospective of his work of the past 60 years, curated by Nicholas Serota — makes reference to the damage done to his standing as a serious artist by an article (“lavishly illustrated with photographs of the casa bella by Horst P Horst”) which appeared in American Vogue in the mid-1960s at around the time Twombly was showing a series of works in New York called Nine Discourses on Commodus, the title of which alone, with its classical uppityness, was sufficient to earn him a tongue-lashing from Donald Judd and others of the minimalist persuasion.

“The Roman apartment where the Twomblys now live, with their six-year-old son, Alessandro, happens to be in a palazzo,” the Vogue journalist noted. “In certain quarters, where it is assumed that avant-garde American artists should live in avant-garde American discomfort, this relatively insignificant fact has led to Twombly being suspected of having fallen for ‘grandeur,’ and somehow betrayed the cause.”

Like Saul Bellow, who as an expatriate living in Paris on a Guggenheim fellowship couldn’t wait to flee the grim view of postwar life taken by the European modernists (the “Wastelanders,” as he called them) and reconnect with the American vernacular, Rauschenberg had gone home to be close to the all-American junk he scavenged for his early combine paintings. When his year was up, in the summer of 1957, Cheever also boarded a boat in Naples with his new, Italian-born son, Federico, and sailed back to participate in the school run and the early-morning commute from Ossining.

But, both in life and in his novels and stories, until his death in 1982 Cheever never stopped returning to “a country of such detail and loveliness that it could not be described.” However, “it seemed to me that a person should live in his own country,” he wrote once, in a story called Boy in Rome, “that there is always something a little funny or queer about people who choose to live in another country. Now my mother has many American friends who speak fluent Italian and wear Italian clothes ... but to me there always seems to be something a little funny about them as if their stockings were crooked or their underwear showed and I think that is always true about people who live in another country. I wanted to go home.”

Twombly, of course, stayed. In 1962, while he was busy pushing away from the restrained understatement of his 1950s work, allowing the rawness and sensuality of his Roman surroundings to stain and stink up his paintings, the surfaces of which he was intent on destroying and scarring, dragging pencils and other sharp instruments through them, Cheever was publishing a quietly transgressive story which, like much of his writing, in retrospect reads like an unwitting commentary on or companion text to the work Twombly was simultaneously making.

In Mene, Mene, Tekel, Upharsin, the narrator, returning to the US after a long absence, enters a stall in the men’s room at Grand Central Station. There, etched into the marble partition (“It might have been a giallo antico, but then I noticed Paleozoic fossils beneath the high polish and guessed that the stone was madrepore”), he finds not the spurting pricks and lewdnesses he was expecting, but, “organized into panels, like the pages of a book,” passages that might have been lifted from the diaries and journals of his neighbors in the well-heeled, well-lit suburbs of New York — or from any one of many late-period Twombly paintings, with their roughly hewn quotes from Rilke and Spenser and Robert Burton, their classic cryptograms and haikus and erudite references to Bacchus and Silenus.

Mene, Mene is a catalogue of such encounters, in toilets on trains and at public urinals all across America, and clearly echoes a scene that crops up close to the end of Cheever’s first novel, The Wapshot Chronicle (1957): “Feeling sick, he went to the toilet, where someone had written on the wall in pencil a homosexual solicitation for anyone who would stand by the water-cooler and whistle Yankee Doodle ... . He stared out of the window at the landscape, seeking in it, with all his heart, some shred of usable and creative truth, but what he looked into were the dark plains of American sexual experience where the bison still roam.”

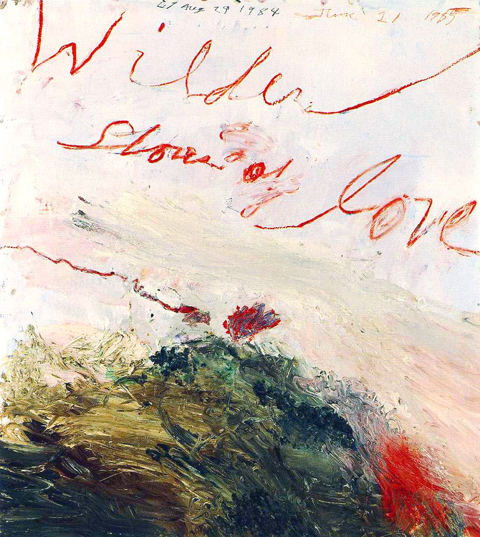

The “he” in Cheever’s novel is a man called “Leander,” who, true to his classical predecessor, drowns while swimming the river he used to work as a pleasure-boat captain. Coincidentally or not, in 1981, around the time he began to spend part of his year in the town of Gaeta, a medieval port between Naples and Rome on the Tyrrhenian Sea, Twombly started work on a four-part painting, Hero and Leandro. Part of the apparatus of the picture is a small panel inscribed with the words “He’s gone; up bubbles all his amorous breath,” the last line of a Keats sonnet, as it happens. But a number of enraptured passages from The Wapshot Chronicle — “The voyage seemed to Leander, from his place at the helm, glorious and sad”; “’Tie me to the mast, Perimedes,’ Leander used to shout when he heard the merry-go-round” — would have served as well.

Twombly’s “literariness” is something that has consistently told against him, along with his fancy foreign ways and his “insinuating elegance.” But his art, as Serota acknowledges in the catalogue, has always been elusive and, for many people, even enthusiasts of contemporary art, unfathomable. Twombly himself has maintained an unusual reticence. In the mid-50s, he wrote a short statement for the Italian art journal L’Esperienza moderna: “To paint involves a certain crisis, or at least a crucial moment of sensation or release; and by crisis it should by no means be limited to a morbid state, but could just as well be one ecstatic impulse.” More than 40 years later, in 2000, he gave an interview to David Sylvester. In between there was nothing. He needed somebody to speak for him. And when, apparently unbeknownst to them both, he wasn’t being ventriloquized by Cheever, he looked to the poets and the ancients, whose words he then tended to violate and smear and inter in paint.

A good number of his drawings, paintings and sculptures consist of little other than an inscription. “Twombly writes as if he were seeking out the meaning of the poetic words through the physical act of producing their graphic signs,” Richard Shiff has written. “The word as disembodied sign becomes the word as embodied mark, imbued with the spirit of a gesture and located in a particular place and time.”

Twombly’s has long been an art of indirection; a palimpsest of obfuscations and excisions, of rubbings out and submergings. Like Rauschenberg, who as a young man spent three weeks erasing a drawing he had acquired from Willem de Kooning, Twombly, in Serota’s words, evokes rather than describes.

Nowhere is his genius for evocation — for suggesting the mood or feeling of a place or a moment — more apparent than in the set of 24 drawings he made in 1959 called Poems to the Sea. “The sea is white three-quarters of the time, just white — early morning,” Twombly told Sylvester. “The Mediterranean at least ... is always just white, white, white. And then, even when the sun comes up, it becomes a lighter white.”

Of the same coast, Cheever, the unseen companion of his days, once wrote: “The light was golden, but then the golden light changed to another color, deeper and rosier ... . Then it paled off, it got so pale that you could see the smoke from the city rising into the air and then through the smoke the evening star turned on, burning like a street light, and I began to count the other stars as they appeared, but very soon they were countless.”

Twombly is a celebratory painter, as Cheever was a celebratory writer. His hope, he once wrote, was “to celebrate a world that lies spread out around us like a bewildering and stupendous dream”; it was to hymn “the sense of life as a privilege, the earth as something splendid to walk on.”

June 23 to June 29 After capturing the walled city of Hsinchu on June 22, 1895, the Japanese hoped to quickly push south and seize control of Taiwan’s entire west coast — but their advance was stalled for more than a month. Not only did local Hakka fighters continue to cause them headaches, resistance forces even attempted to retake the city three times. “We had planned to occupy Anping (Tainan) and Takao (Kaohsiung) as soon as possible, but ever since we took Hsinchu, nearby bandits proclaiming to be ‘righteous people’ (義民) have been destroying train tracks and electrical cables, and gathering in villages

Dr. Y. Tony Yang, Associate Dean of Health Policy and Population Science at George Washington University, argued last week in a piece for the Taipei Times about former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) leading a student delegation to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) that, “The real question is not whether Ma’s visit helps or hurts Taiwan — it is why Taiwan lacks a sophisticated, multi-track approach to one of the most complex geopolitical relationships in the world” (“Ma’s Visit, DPP’s Blind Spot,” June 18, page 8). Yang contends that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has a blind spot: “By treating any

Swooping low over the banks of a Nile River tributary, an aid flight run by retired American military officers released a stream of food-stuffed sacks over a town emptied by fighting in South Sudan, a country wracked by conflict. Last week’s air drop was the latest in a controversial development — private contracting firms led by former US intelligence officers and military veterans delivering aid to some of the world’s deadliest conflict zones, in operations organized with governments that are combatants in the conflicts. The moves are roiling the global aid community, which warns of a more militarized, politicized and profit-seeking trend

This year will go down in the history books. Taiwan faces enormous turmoil and uncertainty in the coming months. Which political parties are in a good position to handle big changes? All of the main parties are beset with challenges. Taking stock, this column examined the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) (“Huang Kuo-chang’s choking the life out of the TPP,” May 28, page 12), the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) (“Challenges amid choppy waters for the DPP,” June 14, page 12) and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) (“KMT struggles to seize opportunities as ‘interesting times’ loom,” June 20, page 11). Times like these can