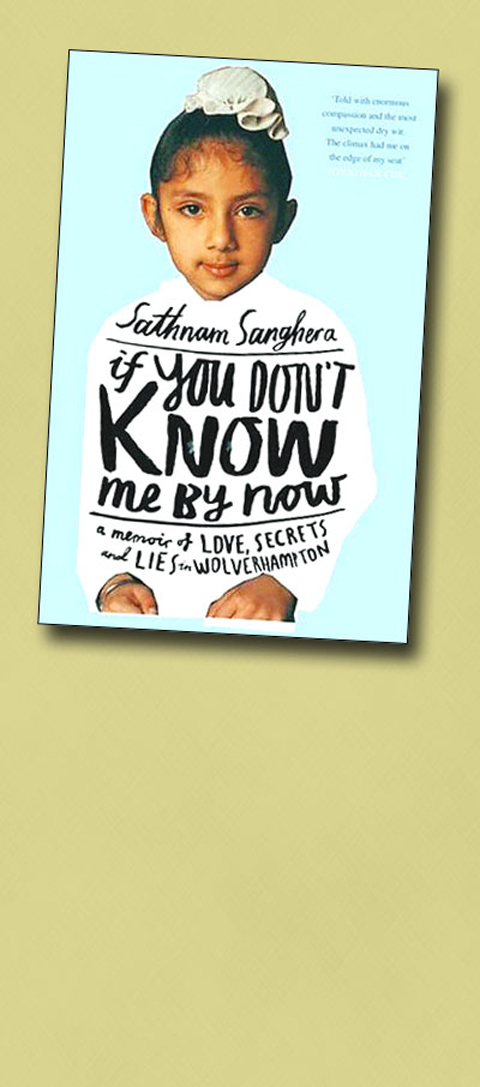

When a writer decides to use up what W. H. Auden described as “capital” — the stuff of life — in a memoir, it is a calculated sacrifice: a loss of privacy in favor of publication. Sathnam Sanghera goes further still. His memoir does not depend on passive reminiscence. It is an absorbing, ongoing drama, played out on the page. Right at the start, he tells us what he has in mind: he is nerving himself to write a letter to his Sikh mother (she speaks no English), which he will pay to have translated (he cannot write in Punjabi). He does not know what her reply will be. But he fears the letter will break her heart.

Its contents, on the face of it, are simple enough: Sanghera cannot consent to an arranged marriage. His mother wants him to marry a nice Sikh girl. He wants to be free to marry as he pleases. When out with English girlfriends, he behaves like a guilty man. Late one night, a distant aunt phones to convict him — he has been spotted with the wrong sort of girl. His mother has been informed. He barely knows the aunt in question and comically describes the call’s peculiarly traumatic effect: “My calves began to perspire, something I’d never experienced before.” You are left in no doubt about how much he needs his mother’s approval. “You see, when it comes down to it, death is a more appetizing prospect than crossing my mother.”

His education has taken him out of one world and into another. He went to Cambridge (where he got a first in English) and became a journalist (on the Financial Times before moving to the Times). In many ways, he has left his family life in Wolverhampton behind. But as a writer he knows how to exist in two places at once. He brings London back to Wolverhampton and is able to use the distance between his two worlds to entertaining effect. I loved the description of his mother’s superstitious welcome of him involving birdseed and a red chili pepper. I also relished the description (his writing is full of gentle, hyperbolic wit) of his mother’s monologues as “ocean liners” because they “require time to change direction.” He smiles affectionately in her direction but laughs, often unkindly, at himself.

It is while he is trying to help reduce the weight of his mother’s grossly overstuffed suitcase — she is preparing for a trip to India — that he finds an item heavier than all the rest. Along with miscellaneous pills is a letter marked: “To whom it may concern” in which he discovers that his father and his sister have schizophrenia. He is 24 and his mother has protected him from the truth all his life.

At one point, he says: “We never look at our parents closely, do we, just as we don’t see them as people.” The book attempts to correct that. It contains the beautifully reconstituted story of his mother’s arranged marriage and its painful aftermath. And he works hard at trying to understand his father and his sister and their suffering. As he reads up about the disease, he monitors his own reactions with dismay: “My father and sister had gone from being my father and sister, two people who behaved a little strangely at times, but two people I loved, to being a collection of symptoms.”

But it is the letter that we are waiting to have answered. It creates and sustains the suspense that has had you hooked throughout. The book could not be more enjoyable, engaging or moving. But I was left feeling uneasy about its private purpose. For the memoir has been used as a tool to influence his mother’s reply, nudge her in the right direction and to protect himself. She is, after all, told that her answer — to his most private question — will be published in his book.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

Lines between cop and criminal get murky in Joe Carnahan’s The Rip, a crime thriller set across one foggy Miami night, starring Matt Damon and Ben Affleck. Damon and Affleck, of course, are so closely associated with Boston — most recently they produced the 2024 heist movie The Instigators there — that a detour to South Florida puts them, a little awkwardly, in an entirely different movie landscape. This is Miami Vice territory or Elmore Leonard Land, not Southie or The Town. In The Rip, they play Miami narcotics officers who come upon a cartel stash house that Lt. Dane Dumars (Damon)