Jan. 26 to Feb. 1

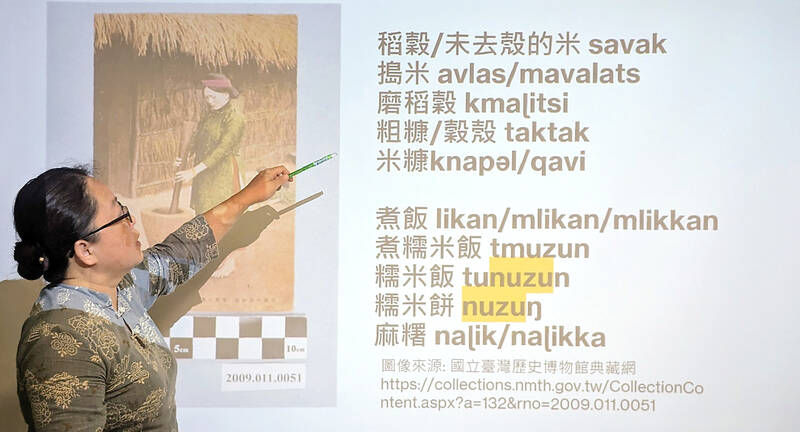

Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan.

Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

In 1936, Japanese anthropologist and linguist Erin Asai located two women who still remembered Basay and recorded a substantial corpus of folk tales and songs. The recordings sat in university archives for decades until they were digitized, giving modern Ketagalan the first clear sense of how the language sounded. Today, they form the basis of new teaching materials.

The Ketagalan were further assimilated and dispersed as Taipei expanded, many now living in apartment buildings and uncertain or unaware of their identity. Teachers Rosey Peng (彭凌, Ketagalan name Avas) and Chen Chin-wan (陳金萬) hope that by learning Basay together, they can reclaim a sense of community — although the classes are open to anyone interested.

“It’s a platform for people to meet and connect, and for possible descendants to find their way home,” Peng says.

Photo courtesy of Chen Kun-mu

HISTORICAL RECORDS

Basay was first mentioned in 1632 by Spanish missionary Jacinto Esquivel, who claimed that it was widely understood across Taiwan — likely an overstatement. It’s believed to have been spoken in today’s Taipei, New Taipei City, Keelung and parts of Yilan, although individual settlements such as Kipatauw in Beitou had their own related languages. Basay speakers along the Keelung coast were skilled navigators who controlled regional trade, and other groups may have learned it for commerce.

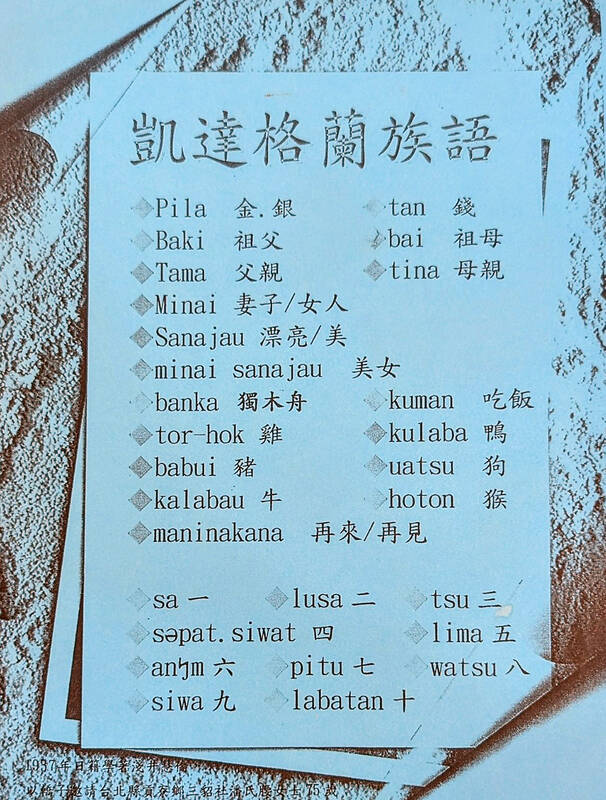

Esquivel published a vocabulary of the Indigenous peoples living in and around the area that is today known as Tamsui District (淡水), but the manuscript remains lost. No record of Taipei’s Indigenous languages appeared again until 1896, when Japanese anthropologist Kanori Ino visited settlements in Taipei and Yilan, collecting a handful of words per location from elderly residents.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

Some of these terms lingered long even after the language ceased to be used. Kipatauw church elder Pan Hui-an (潘慧安), 88, recalls his family using Indigenous words for certain items, while Baode Temple (保德宮) director Pan Kuo-liang (潘國良) remembers his grandmother speaking phrases he could not understand.

Asai likely first arrived in Taiwan in 1927 to conduct field research, writes musicologist Lin Ching-tsai (林清財). Over the following years, he worked with Taihoku Imperial University professor Naoyoshi Ogawa to document indigenous languages across Taiwan. In 1936, he succeeded Ogawa after the latter retired.

In October 1936, Asai met 75-year-old Pan Shih-yao (潘氏腰), who lived in the settlement of Sinshe (新社) in Gongliao District (貢寮), New Taipei City. She provided nearly 1,000 words, several sentences and two short texts. Six decades later, her great-grandson Pan Yao-chang (潘耀璋) would become one of the earliest leading figures in the Ketagalan revival movement.

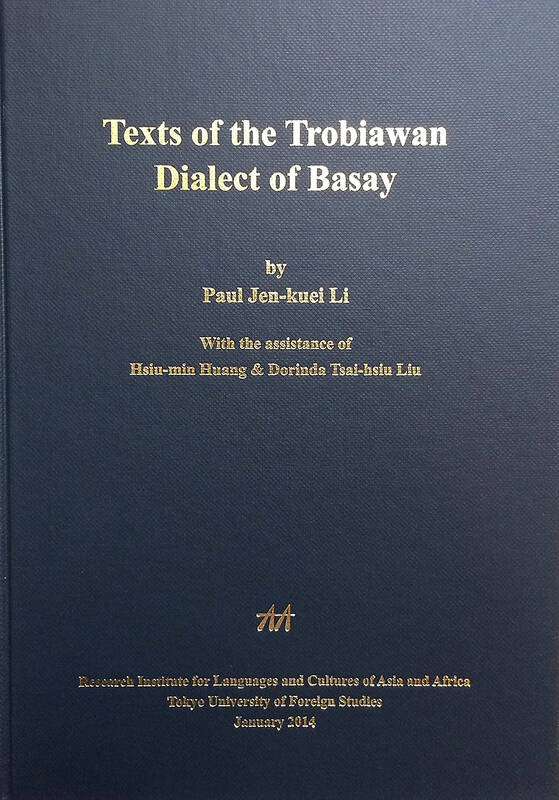

Photo courtesy of Amazon

In December, Asai located 69-year-old Ipay in Yilan County, a fluent speaker of the Trobiawan dialect of Basay. He collected a word list, more than a dozen folktales and myths, and numerous songs. After a month and a half of recording, Ipay fell ill and died in March 1937.

EARLY REVIVAL EFFORTS

Asai never published his Basay data. However, linguists Shigeru Tsuchida, Yukihiro Yamada and Tsunekazu Moriguchi in 1991 organized his materials into a dictionary. This text, along with Ino’s word lists, was used by Ketagalan activists in the early 2000s to study the language.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

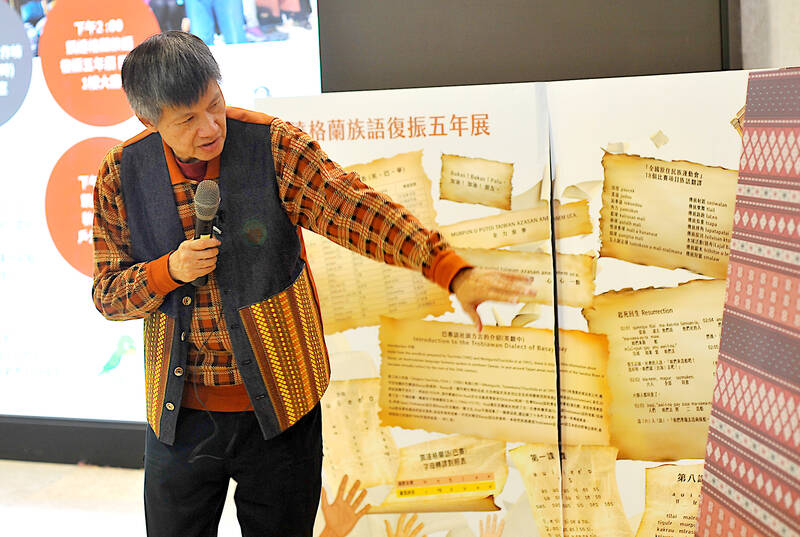

A turning point came when Ketagalan descendant Chen Chin-wan visited linguist Paul Jen-kuei Li (李壬癸) and discovered that he had published the book Texts of the Trobiawan Dialect of Basay in 2014. Analyzing Ipay’s data, Li had compiled a word-for-word grammatical analysis of the texts with translations in English and Chinese.

“I’m not a language expert, so this made me surprised, happy and a little scared,” Chen says. “But once I knew what we had, I felt a responsibility to act. We started from scratch just like that.”

Chen brought the book to Pan Hui-an and other Ketagalan elders at Independence Presbyterian Church in Xinbeitou, where they began studying it together. They read the text sentence by sentence, and progress was slow. Then the COVID-19 pandemic brought this effort to a halt.

Later, Chen began working with Peng and the Cognitive Approach Development Association for Indigenous Language Education (默示原住民語教學發展協會). Peng became involved in Ketagalan revival efforts after discovering that her great-great-great-grandfather had been the headman of Cattayo (also spelled Tatayou), a former settlement along the Keelung River in today’s Songshan District (松山) in Taipei. She also has Kipatauw and Litsiouck ancestry.

The recordings had not been accessible as they were on fragile wax cylinder records, but the group later found that they had been digitized and were available at National Taiwan University. For the first time, they could hear what Basay actually sounded like.

TEACHING THE LANGUAGE

Peng draws from the vivid stories and cultural details in the Trobiawan texts and other historic materials to bring Basay language and culture to life in her talks and classes. From Ketagalan food and drink habits to marriage customs, and folk tales such as “The Deceased Daughter Cooked for her Parents” and “Transforming into a Bird,” these materials offer a glimpse into a lost culture. Spanish-era texts record the Basay word masimanamananur, an activity where community members air grievances in public after drinking.

“These cultural details are what draw people to the language,” Peng says. “When people see what’s interesting and impressive about the Ketagalan, they feel proud and connected, and then they want to learn more.”

Only about 10 of the 30 or so students in last year’s class were Ketagalan or searching for their roots, Chen says, while the rest were linguistics students, scholars and others interested in Indigenous culture. Peng says this mix has made the classes more of a collaborative experience, with students and teachers working together to solve linguistic problems.

The language is still a work in progress. While the stories contain vivid, emotional sentences, many basic words and greetings are missing. When a term is absent, Peng and Chen draw from other regional languages such as Kipatauw, and when that fails they may create new words.

The goal, Peng and Chen say, is that one day people will be able to engage in simple daily conversations in Basay. It will take time, but the classes are a start.

“I have confidence,” Peng says. “As long as Taiwan exists, future generations will keep studying [Basay], finding more pieces of the puzzle and continue passing it on.”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Recently the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and its Mini-Me partner in the legislature, the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), have been arguing that construction of chip fabs in the US by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電) is little more than stripping Taiwan of its assets. For example, KMT Legislative Caucus First Deputy Secretary-General Lin Pei-hsiang (林沛祥) in January said that “This is not ‘reciprocal cooperation’ ... but a substantial hollowing out of our country.” Similarly, former TPP Chair Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) contended it constitutes “selling Taiwan out to the United States.” The two pro-China parties are proposing a bill that

March 9 to March 15 “This land produced no horses,” Qing Dynasty envoy Yu Yung-ho (郁永河) observed when he visited Taiwan in 1697. He didn’t mean that there were no horses at all; it was just difficult to transport them across the sea and raise them in the hot and humid climate. “Although 10,000 soldiers were stationed here, the camps had fewer than 1,000 horses,” Yu added. Starting from the Dutch in the 1600s, each foreign regime brought horses to Taiwan. But they remained rare animals, typically only owned by the government or

Institutions signalling a fresh beginning and new spirit often adopt new slogans, symbols and marketing materials, and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) is no exception. Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文), soon after taking office as KMT chair, released a new slogan that plays on the party’s acronym: “Kind Mindfulness Team.” The party recently released a graphic prominently featuring the red, white and blue of the flag with a Chinese slogan “establishing peace, blessings and fortune marching forth” (締造和平,幸福前行). One part of the graphic also features two hands in blue and white grasping olive branches in a stylized shape of Taiwan. Bonus points for

Last month, media outlets including the BBC World Service and Bloomberg reported that China’s greenhouse gas emissions are currently flat or falling, and that the economic giant appears to be on course to comfortably meet Beijing’s stated goal that total emissions will peak no later than 2030. China is by far and away the world’s biggest emitter of greenhouse gases, generating more carbon dioxide than the US and the EU combined. As the BBC pointed out in their Feb. 12 report, “what happens in China literally could change the world’s weather.” Any drop in total emissions is good news, of course. By