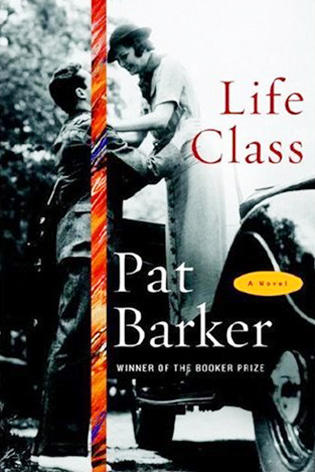

With her new novel, Life Class, Pat Barker returns to the subject of World War I - a subject that earned her immense acclaim in the 1990s with her Regeneration trilogy (Regeneration, The Eye in the Door and The Ghost Road), an artful improvisation on the lives of the poets Siegfried Sassoon, Wilfred Owen, Robert Graves and their compatriots, which unfurled into a fierce meditation on the horrors of war and its psychological aftermath.

After several intriguing but lumpy novels set in the present or near-present, it becomes clear to the reader that World War I resonates with Barker with special force, for Life Class possesses the organic power and narrative sweep that her recent books with more contemporary settings lack.

Perhaps it's that Barker's tactile ability to conjure the fetid horror of the trenches and the field hospitals has little applicable use in describing daily life in modern-day Britain. Perhaps it's that her narrative abilities are spurred by the sort of galvanic changes ushered in by the Great War - a social and cultural earthquake that helped midwife an era of modernism and irony and doubt. Perhaps it's that historical research (more than a dozen works are listed as source material at the end of this volume) and the use of historical characters somehow lend ballast and gravitational weight to her imaginings.

In any case, Life Class represents her best work since The Ghost Road, for which she received the 1995 Booker Prize.

The three central characters in Life Class are students at the Slade School of Art in London, studying under the tutelage of the famous Henry Tonks. Elinor, the charismatic center of the love triangle, seems loosely based on Dora Carrington, the talented painter who would become a Bloomsbury acolyte. Her suitor Neville seems loosely based on Christopher Nevinson, an art student who served with the medical corps and who later became known for his paintings of the war. Elinor's other suitor, Paul, in contrast, seems more like a full-blown fictional creation - a sort of Everyman, like Billy Prior in the Regeneration novels, representative of the many Englishmen of his generation who found their lives and expectations turned upside down by the Great War.

When we first meet these three young artists, war is still just a distant rumor on the Continent, and they and their fellow students are pursuing a bohemian life in London. There are lots of late nights out, lots of flirting and romantic intrigue, lots of ruminating about art and aesthetics and the meaning of Beauty and Truth. Paul has a brief affair with a model named Teresa and an unpleasant encounter with her estranged husband, who has been stalking her.

After Teresa leaves town, Paul finds himself increasingly drawn to her friend Elinor, one of the Slade's more gifted students, who is being pursued by Neville, a former Slade student who has started to establish a reputation as an up-and-coming painter in London. The three hang out together as friends, but Paul and Neville vie for Elinor's attentions. Neville worries that Paul might have more in common with Elinor than he does.

Paul worries that Elinor won't sleep with him and that he might not have enough talent to make it as an artist. And Elinor worries that all the independence she's established in London as a woman and an artist count for nothing with her relatives, who regard painting as little but a pleasant hobby.

All this changes with the arrival of the war, which suddenly makes all their reveries about love and art seem childish and naive. Paul ends up in Belgium working as a medic, tending to the wounded, and Neville ends up in a nearby town, driving ambulances.

Elinor, alone, remains committed to "an iron frivolity," determined to pursue her painting and ignore all news of the war. She visits Paul in the small Belgian town near the front where he is serving - one of the novel's few sequences that feels improbable and forced - and the two promptly start squabbling about the proper role of art in wartime. Paul argues for an art that would bear witness to the wounds of war - "it's not right their suffering should just be swept out of sight," he says of the wounded soldiers - while Elinor declares that art should only depict "the things we choose to love," not things "imposed on us from the outside."

In depicting the effect that World War I has on her three young protagonists, Barker takes care never to sentimentalize them. Although she writes effectively from each of their points of view, communicating their hopes and fears and dreams, they emerge as rather selfish, unsympathetic individuals, who have all cultivated a certain emotional detachment in the service of their art. That detachment helps Paul and Neville survive the horrors they witness during the war, but it also cuts them off from genuine emotional connection.

Elinor's determination not to think about the war comes off as narcissistic denial. Neville's celebrated success in London with his war paintings feels perilously close to war profiteering. And Paul's "learning not to care" about the wounded soldiers he tends to sometimes seems less like a defensive survival mechanism than a solitary man's rationalization of his own difficulty in feeling.

As she did in her Regeneration trilogy, Barker conjures up the hellish terrors of the war and its fallout with meticulous precision. Grievously injured soldiers crying out for morphine that does not exist; field surgeons tossing bits of damaged flesh into buckets; civilians scurrying for safety as bombs torpedo their homes and gardens; columns of rain-drenched men marching toward the front in "gleaming capes and helmets, like mechanical mushrooms" - such images and the ineradicable memory of these sights are captured with unsparing clarity by Barker in these pages, as are the less visible scars they leave on the psyches of soldiers, doctors and witnesses alike.

June 23 to June 29 After capturing the walled city of Hsinchu on June 22, 1895, the Japanese hoped to quickly push south and seize control of Taiwan’s entire west coast — but their advance was stalled for more than a month. Not only did local Hakka fighters continue to cause them headaches, resistance forces even attempted to retake the city three times. “We had planned to occupy Anping (Tainan) and Takao (Kaohsiung) as soon as possible, but ever since we took Hsinchu, nearby bandits proclaiming to be ‘righteous people’ (義民) have been destroying train tracks and electrical cables, and gathering in villages

Dr. Y. Tony Yang, Associate Dean of Health Policy and Population Science at George Washington University, argued last week in a piece for the Taipei Times about former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) leading a student delegation to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) that, “The real question is not whether Ma’s visit helps or hurts Taiwan — it is why Taiwan lacks a sophisticated, multi-track approach to one of the most complex geopolitical relationships in the world” (“Ma’s Visit, DPP’s Blind Spot,” June 18, page 8). Yang contends that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has a blind spot: “By treating any

Swooping low over the banks of a Nile River tributary, an aid flight run by retired American military officers released a stream of food-stuffed sacks over a town emptied by fighting in South Sudan, a country wracked by conflict. Last week’s air drop was the latest in a controversial development — private contracting firms led by former US intelligence officers and military veterans delivering aid to some of the world’s deadliest conflict zones, in operations organized with governments that are combatants in the conflicts. The moves are roiling the global aid community, which warns of a more militarized, politicized and profit-seeking trend

This year will go down in the history books. Taiwan faces enormous turmoil and uncertainty in the coming months. Which political parties are in a good position to handle big changes? All of the main parties are beset with challenges. Taking stock, this column examined the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) (“Huang Kuo-chang’s choking the life out of the TPP,” May 28, page 12), the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) (“Challenges amid choppy waters for the DPP,” June 14, page 12) and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) (“KMT struggles to seize opportunities as ‘interesting times’ loom,” June 20, page 11). Times like these can