Sandra Boynton's studio, in a converted barn next to her Connecticut home, bears the milestones of her singular career: a long rack of greeting cards featuring quirkily drawn animals; a room full of small, sturdy children's books, with names like Snuggle Puppy! and Barnyard Dance!; and, upstairs, where she does much of her work, old-time radios and jukeboxes representing her more recent foray into music CDs for children.

Boynton's CDs have garnered three gold records and one Grammy nomination. These accomplishments, on top of the hundreds of millions of cards and tens of millions of books she has sold, are all the happy - and profitable - results of an unconventional approach to business.

As an entrepreneur, Boynton maintains a firm grasp on market realities and her finances, but she says she has succeeded by refusing to make money her main objective. Instead, she says, she has focused on the creative process, her artistic autonomy, her relationships and how she uses her time.

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

"I don't do things differently to be different; I do what works for me," she says. "To me, the commodity that we consistently overvalue is money, and what we undervalue is our precious and irreplaceable time."

While Boynton may make all of this sound relatively straightforward, she has overcome hurdles in three industries that have routinely tripped up or roundly laid low legions of would-be entrepreneurs.

Boynton, 54, describes what she calls an "absurdly happy childhood" in Philadelphia. The third of four daughters, she attended Germantown Friends, a K-12 Quaker school famed for its arts education and interdisciplinary teaching. Her father, Robert Boynton, was an English teacher at the school. "The best English teacher I ever had," she says.

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

She was fascinated by business at an early age and remembers selling pretty yellow flowers door to door for a dime when she was 8.

When Boynton was 14, a local newspaper printed drawings from an exhibit of her school artwork. She used the US$40 she earned from her first published work to invest in two shares of AT&T - though she mistakenly thought she was buying shares of IBM She still has the stock but has no clue how much it is worth.

Stocks held a special glamour for her: Her grandfather worked at a silver company, rising from the mailroom to the vice president's perch.

In addition to her investing activity, she developed a strong interest in art, music, literature and writing - all of which were central to the Friends curriculum. The school was so stimulating, academically and artistically, she says, that her first year at Yale was a disappointment.

At Yale, she majored in English and became involved in drama courses and productions. She also worked on her drawing. Ever the entrepreneur, she started illustrating gift enclosure cards that were precursors of her animal-populated greeting cards.

In 1974, Boynton met Phil Friedmann, a partner in Recycled Paper Greetings, a greeting card company based in Chicago, at a stationery trade show. After Friedmann and his business partner, Mike Keiser, saw Boynton's work, they asked her to start making cards for their company.

They wanted to pay her a flat rate. Though she was only 21 and unknown, Boynton, who had learned a lesson or two from her father's other careers as a writer and publisher, demanded royalties.

"We quickly relented," Keiser recalls of the royalty negotiations. It was a shrewd move on his part, too. He says that over about a decade - from the mid-1970s to the mid-1980s - revenue at Recycled Paper went from US$1 million to US$100 million, largely because of the popularity of Boynton cards. Boynton has made 4,000 different cards for Recycled Paper, including the still popular Hippo Birdies 2 Ewes birthday card.

By Keiser's rough estimate, Boynton has sold around a half-billion cards, which, he says, makes her one of the best-selling card creators of all time.

Her cards have become such a part of the mainstream that it is easy to forget how radical they were when they were introduced. Dominated by powerhouses like Hallmark and American Greetings, the card industry in the 1970s relied on flowery, color-saturated art and equally flowery prose, written in flourishes and curlicues.

Boynton's cards, on the other hand, were populated with cats, cows, hippos, ducks, sheep, dragons and various other beasts, humanized through the placement of a dot for a pupil, or a single, expressive arc for an eyelid or mouth. She was also among the first greeting card artists to use white backgrounds.

Her cards were thoughtful, wry and whimsical. While the sentiments may have been unconventional, they resonated with the public.

"Things are getting worse," said one card that featured a bewildered hippo. On the inside the card reads "please send chocolate."

Whimsy, it turns out, had been undervalued. And the big card companies eventually took some of their artistic cues from her.

After the cards came the books. Continuing with the chocolate theme, in 1982 Boynton published a general market book titled Chocolate: the Consuming Passion that became a best seller. Its publisher, the Workman Publishing Co, went on to print some of her children's board books - small books with thick, boardlike pages, with five to 10 rhythmic words per page.

The books feature some of the same furry and feathery characters that her cards do, presenting a world that her editor of 27 years, Suzanne Rafer, calls "safe, unexpected and pleasurable" for children.

The most popular board book by Workman, Barnyard Dance! ("Bow to the horse. Bow to the cow. Bow to the horse if you know how.") was published in 1993 and has 2.3 million copies in print.

From books, Boynton decided to extend her rhythmic sensibility into song. She says she was helped along by "dumb luck."

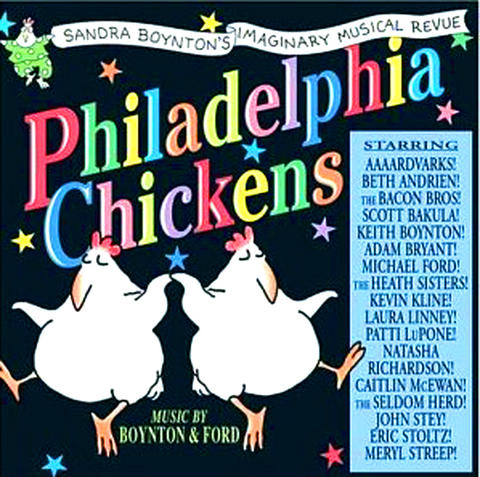

When she was working on the album Philadelphia Chickens in 2001, for instance, she told Mike Ford, her songwriting partner, that Meryl Streep (a fellow Yale alumna and a friend) was the only person who could do justice to the song Nobody Understands Me.

The very next day, Streep happened to stop by her studio. She recorded the song and then suggested that the actor Kevin Kline might want to record one, too. He sang Busybusybusy. Another friend of Boynton's, Laura Linney, sang for the album, and Linney helped arrange for Eric Stoltz to put in an appearance.

Buoyed by her Hollywood supporters, Boynton approached some of the biggest names in the music industry - including Alison Krauss, Blues Traveler and the Spin Doctors - to contribute to her next album, Dog Train. From there, she was able to persuade some of her music idols - including Neil Sedaka, B.B. King, Steve Lawrence and Davy Jones - to sing on her most recent effort, called Blue Moo: 17 Jukebox Hits From Way Back Never.

Boynton's studio is not far from the farmhouse that she and her husband, McEwan - also a children's book author - bought 28 years ago. In addition to creating greeting cards and children's books, the couple also raised four children there, now ages 18 to 28.

There is no Inc or LLC after her name. She prefers to be an unincorporated business with an orbit of "licensees," for lack of a better word, around her.

Whenever she has made products like stuffed animals, mugs, jewelry, sheets or towels, she has maintained control over the finished product so it doesn't stray from her vision - or saturate the market.

"Theoretically, I could choose to trade artistic autonomy and pride in my work for increased income - say, by broadly licensing my characters to be used for television," she says. But that would be foolish, she says.

"I love what I do, I love the people I work with, I care very much about the value of the work I create, and I don't need more money than I have. This is not revolutionary philosophy. It's just common sense."

The canonical shot of an East Asian city is a night skyline studded with towering apartment and office buildings, bright with neon and plastic signage, a landscape of energy and modernity. Another classic image is the same city seen from above, in which identical apartment towers march across the city, spilling out over nearby geography, like stylized soldiers colonizing new territory in a board game. Densely populated dynamic conurbations of money, technological innovation and convenience, it is hard to see the cities of East Asia as what they truly are: necropolises. Why is this? The East Asian development model, with

June 16 to June 22 The following flyer appeared on the streets of Hsinchu on June 12, 1895: “Taipei has already fallen to the Japanese barbarians, who have brought great misery to our land and people. We heard that the Japanese occupiers will tax our gardens, our houses, our bodies, and even our chickens, dogs, cows and pigs. They wear their hair wild, carve their teeth, tattoo their foreheads, wear strange clothes and speak a strange language. How can we be ruled by such people?” Posted by civilian militia leader Wu Tang-hsing (吳湯興), it was a call to arms to retake

Desperate dads meet in car parks to exchange packets; exhausted parents slip it into their kids’ drinks; families wait months for prescriptions buy it “off label.” But is it worth the risk? “The first time I gave him a gummy, I thought, ‘Oh my God, have I killed him?’ He just passed out in front of the TV. That never happens.” Jen remembers giving her son, David, six, melatonin to help him sleep. She got them from a friend, a pediatrician who gave them to her own child. “It was sort of hilarious. She had half a tub of gummies,

The wide-screen spectacle of Formula One gets a gleaming, rip-roaring workout in Joseph Kosinski’s F1, a fine-tuned machine of a movie that, in its most riveting racing scenes, approaches a kind of high-speed splendor. Kosinski, who last endeavored to put moviegoers in the seat of a fighter jet in Top Gun: Maverick, has moved to the open cockpits of Formula One with much the same affection, if not outright need, for speed. A lot of the same team is back. Jerry Bruckheimer produces. Ehren Kruger, a co-writer on Maverick, takes sole credit here. Hans Zimmer, a co-composer previously, supplies the thumping