With his allegiance to dewy-eyed innocence and earnest sentimentality, the illustrator Norman Rockwell has often been mocked for creating an America that never was and never will be.

But Kevin Rivoli, a photojournalist in upstate New York, will tell you that's just not true. He knows because he's documented it.

Rivoli has spent the past 15 years capturing timeless moments in contemporary America — the solemn christenings and squirmy first haircuts, the town meetings and patriotic parades, the youthful shenanigans and the mature reverence symbolized by elderly hands resting on a well-thumbed bible.

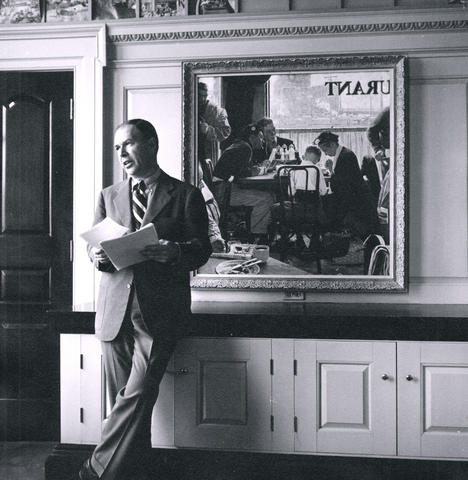

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

He calls his project In Search of Norman Rockwell's America, and by autumn his photographs will have grown into a book, published by Prestel, and a traveling exhibition, overseen by International Arts and Artists, that juxtaposes Rivoli's images with Rockwell's.

The project has received the blessing of the Rockwell family; the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts; and Curtis Publishing, owners of the Saturday Evening Post, whose covers Rockwell illustrations adorned. Additionally, some scholars hope that Rivoli's images will put the old criticism about Rockwell to rest once and for all.

“I cover a lot of small-town America,” said Rivoli, 47, a contract photographer with the Associated Press who occasionally does work for the New York Times. “I'm not a war photographer, I'm not in metropolitan America. I tend to look for connections between people.

“Rockwell did a lot of that in his artwork,” he said.

Rivoli connected with Rockwell 18 years ago when he and his future wife, Michele, visited the Rockwell Museum. There they learned of critics' contentions that Rockwell's images were trite and kitschy figments of their creator's nostalgic imagination.

“Kevin immediately said, ‘He's not creating an America that doesn't exist,'” Michele Rivoli, a former reporter, recalled. “'Those moments do exist, and I have them on film.'”

Over time Rivoli collected more than 120 such images, mostly the result of spontaneous moments snapped during assignments in upstate New York. For example, a photo of altar boys at a 1996 wedding in Otisco recalls the Choirboy cover Rockwell drew for the Post in 1954. “When I go into an assignment that could be boring, I try to look for the picture within the picture, the essence of Norman Rockwell,” he said. “I always think, ‘How would he paint this?'”

For a while the Rivolis owned a gallery near their home outside Auburn, in the Finger Lakes region. But they closed shop two and a half years ago to spend more time with their small twin sons.

“My concern was that Kevin wasn't going to have a creative outlet for people to enjoy what he did,” Michele Rivoli said. So she suggested that he compile his images into a book.

“One day we started looking at Rockwell's artwork, and it was kind of uncanny, in that the pictures would match up,” Rivoli said. “There were a lot of parallels between what I was shooting over the years and what he painted.”

The Rivolis sent the images to the Rockwell Museum and to John Rockwell, Norman's grandson, who granted the Rivolis the rights to use the artist's art and name.

“I thought it looked great, and I thought it was nice that he was inspired by Norman's pictures,” John Rockwell said. “I think the moments in Norman's pictures, if they actually didn't take place, they could have taken place. I think Kevin's pictures do show that there's a side of America that still exists.”

Rivoli's images may help buttress the argument that Rockwell's illustrations helped to give rise to feature photojournalism in the 1950s and 1960s.

“Rockwell really taught photographers to see those common everyday moments, which he defined through his covers for the Saturday Evening Post,” said Andrew Mendelson, chairman of the journalism department at Temple University.

“The era of illustrators is really over, and in my argument that era has been replaced by photojournalism,” said Mendelson, who has written about Rockwell's impact for publications like Journalism History.

June 23 to June 29 After capturing the walled city of Hsinchu on June 22, 1895, the Japanese hoped to quickly push south and seize control of Taiwan’s entire west coast — but their advance was stalled for more than a month. Not only did local Hakka fighters continue to cause them headaches, resistance forces even attempted to retake the city three times. “We had planned to occupy Anping (Tainan) and Takao (Kaohsiung) as soon as possible, but ever since we took Hsinchu, nearby bandits proclaiming to be ‘righteous people’ (義民) have been destroying train tracks and electrical cables, and gathering in villages

This year will go down in the history books. Taiwan faces enormous turmoil and uncertainty in the coming months. Which political parties are in a good position to handle big changes? All of the main parties are beset with challenges. Taking stock, this column examined the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) (“Huang Kuo-chang’s choking the life out of the TPP,” May 28, page 12), the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) (“Challenges amid choppy waters for the DPP,” June 14, page 12) and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) (“KMT struggles to seize opportunities as ‘interesting times’ loom,” June 20, page 11). Times like these can

Dr. Y. Tony Yang, Associate Dean of Health Policy and Population Science at George Washington University, argued last week in a piece for the Taipei Times about former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) leading a student delegation to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) that, “The real question is not whether Ma’s visit helps or hurts Taiwan — it is why Taiwan lacks a sophisticated, multi-track approach to one of the most complex geopolitical relationships in the world” (“Ma’s Visit, DPP’s Blind Spot,” June 18, page 8). Yang contends that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has a blind spot: “By treating any

Swooping low over the banks of a Nile River tributary, an aid flight run by retired American military officers released a stream of food-stuffed sacks over a town emptied by fighting in South Sudan, a country wracked by conflict. Last week’s air drop was the latest in a controversial development — private contracting firms led by former US intelligence officers and military veterans delivering aid to some of the world’s deadliest conflict zones, in operations organized with governments that are combatants in the conflicts. The moves are roiling the global aid community, which warns of a more militarized, politicized and profit-seeking trend