A kitsch extravaganza aquiver with trembling bosoms, booming guns and wild energy, Elizabeth: The Golden Age tells, if more often shouts, the story of the bastard monarch who ruled England with an iron grip and two tightly closed legs. It's the story of a woman, played by the irresistibly watchable Cate Blanchett, who sublimated her libidinal energies through court intrigue until she found sweet relief by violently bringing the Spanish Empire to its knees.

But that's getting ahead of this story, which begins in 1585 when Queen Elizabeth hit 52, though the film seems to put her closer to 38, Blanchett's actual age. The blurring of fact and fancy is, of course, routine with this kind of opulent big-screen production, in which the finer points of history largely take a back seat to personal melodrama and lavish details of production design and costumes. In this regard The Golden Age may set a standard for such an adulterated form: it's reductive, distorted and deliriously far-fetched, but the gowns are fabulous, the wigs are a sight and Clive Owen makes a dandy Errol Flynn, even if he's really meant to be Walter Raleigh, the queen's favorite smoldering slab of man meat.

When Raleigh first swaggers into the court, he's toting a trunk of New World goodies, including some tobacco leaves that, when smoked, he promises with an insinuating smile, are very "stimulating." Hearing that Raleigh has named a swath of New World land Virginia in her honor, Elizabeth seems exceedingly eager for stimulation. She may be a virgin or virginesque, but she's far from cloistered. She surrounds herself with female pets ("My bitches wear my collars"), the loveliest of whom is Bess Throckmorton (Abbie Cornish). Bess holds the queenly hand, caresses the royal head and keeps the imperial body intimate company, suggesting that Elizabeth abandoned the metaphoric sword but not the chalice.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF UIP

The director, Shekhar Kapur, who put Blanchett through her flouncing paces in Elizabeth, the rather more restrained 1998 film about the monarch's earlier years, doesn't spend much time pondering the Sapphic possibilities, mostly because he has armies to unleash, conspiracies to uncork and one head to lop off (Samantha Morton as Mary Stuart). Even so, despite the hurried, sporadically frantic pace, there are a few nice moments in which Elizabeth uses Bess and Raleigh as erotic puppets, turning them into expressions of her own masculine and feminine selves, as if she were a child playing naughty with Barbie and Ken. In her spectral face you see a lonely soul trying to hold onto sanity, to a thread of real life.

Owen looks as if he's having a grand time, whether he's revving Elizabeth up with his tales of seafaring adventure, nuzzling a swooning supplicant or hanging off a ship's rigging as the wind gently stirs his chest hair. With his seafaring movie tan and muscular physicality, he matches up well against the forceful Blanchett, whose strange beauty adds to the queen's otherworldly effect. The Elizabeth of this film bears little relation to the flushed young woman of the first film, who had not yet been unmoored from the merely mortal. The spring lamb is no more, and with her Kabuki-white mask and palace rituals, this older, ethereal Elizabeth on occasion seems like a space alien, which, in some ways, is what she has become.

Written by William Nicholson and Michael Hirst, The Golden Age has sweep and momentum and almost as many mood shifts and genre notes as the queen has dresses. It's intentionally playful and an inadvertent giggle, an overripe melodrama that's by turns a bodice-ripper, a cloak-and-dagger thriller and a serious-minded historical drama with contemporary overtones.

PHOTO: AP

The first film opened with persecuted Protestants roasting over an open fire courtesy of Elizabeth's predecessor; this film leads off with a scheming King Philip II of Spain, her former brother-in-law (Jordi Molla), who wants to dethrone the Protestant queen by igniting a Catholic-led holy war. The resulting conspiracy, with its ominous monks and Latin chants, reeks of The Da Vinci Code, as well as a more urgently modern struggle.

For much of The Golden Age, the filmmakers flirt suggestively with the idea that the English or perhaps the English-speaking world is engaged in another holy war against another set of radical fundamentalists. By the time the Spanish Armada has set sail for England, and Elizabeth has donned armor and a flowing red wig to rouse her waiting troops to victory, the suggestive has become explicit. Declaiming from atop her white horse, her legs now conspicuously parted as she straddles the jittery, stamping animal, she invokes God and country, blood and honor, life and death, bringing to mind at once Joan of Arc, Henry V, Winston Churchill and Tony Blair in one gaspingly unbelievable, cinematically climactic moment. The queenly body quakes as history and fantasy explode.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF UIP

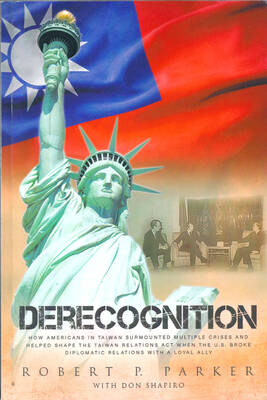

One of the biggest sore spots in Taiwan’s historical friendship with the US came in 1979 when US president Jimmy Carter broke off formal diplomatic relations with Taiwan’s Republic of China (ROC) government so that the US could establish relations with the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Taiwan’s derecognition came purely at China’s insistence, and the US took the deal. Retired American diplomat John Tkacik, who for almost decade surrounding that schism, from 1974 to 1982, worked in embassies in Taipei and Beijing and at the Taiwan Desk in Washington DC, recently argued in the Taipei Times that “President Carter’s derecognition

This year will go down in the history books. Taiwan faces enormous turmoil and uncertainty in the coming months. Which political parties are in a good position to handle big changes? All of the main parties are beset with challenges. Taking stock, this column examined the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) (“Huang Kuo-chang’s choking the life out of the TPP,” May 28, page 12), the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) (“Challenges amid choppy waters for the DPP,” June 14, page 12) and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) (“KMT struggles to seize opportunities as ‘interesting times’ loom,” June 20, page 11). Times like these can

JUNE 30 to JULY 6 After being routed by the Japanese in the bloody battle of Baguashan (八卦山), Hsu Hsiang (徐驤) and a handful of surviving Hakka fighters sped toward Tainan. There, he would meet with Liu Yung-fu (劉永福), leader of the Black Flag Army who had assumed control of the resisting Republic of Formosa after its president and vice-president fled to China. Hsu, who had been fighting non-stop for over two months from Taoyuan to Changhua, was reportedly injured and exhausted. As the story goes, Liu advised that Hsu take shelter in China to recover and regroup, but Hsu steadfastly

You can tell a lot about a generation from the contents of their cool box: nowadays the barbecue ice bucket is likely to be filled with hard seltzers, non-alcoholic beers and fluorescent BuzzBallz — a particular favorite among Gen Z. Two decades ago, it was WKD, Bacardi Breezers and the odd Smirnoff Ice bobbing in a puddle of melted ice. And while nostalgia may have brought back some alcopops, the new wave of ready-to-drink (RTD) options look and taste noticeably different. It is not just the drinks that have changed, but drinking habits too, driven in part by more health-conscious consumers and