A little boy running from the people who killed his mother, brother and sister is lost for months in a dark forest in Eastern Europe. He survives on wild berries and ties himself to trees to escape the howling wolves. Frozen and starving, he happens upon a hut that holds out the promise of food and warmth, but as with the hut in Hansel and Gretel, the promise is cruelly deceptive, and again he narrowly escapes death. Eventually he is rescued by soldiers. But they are dangerous, too, and he must hide from them the truth about himself. It is a truth so frightening that as time passes he gradually forgets who he is, to the point that he cannot even remember his name.

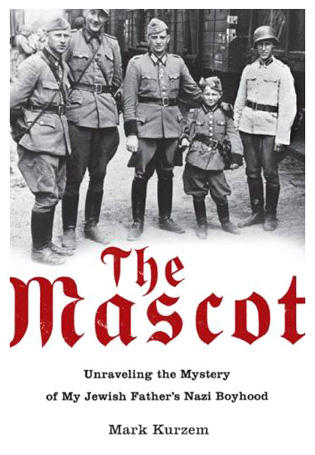

It could be a fairy tale from the Brothers Grimm. But The Mascot: Unraveling the Mystery of My Jewish Father's Nazi Boyhood, by the Australian writer Mark Kurzem, is a true story. Part mystery, part memory puzzle, it is written in the polished style of a good thriller, and it is spellbinding.

Kurzem begins the book in 1997, with his father, Alex, a television repairman in his 70s, suddenly arriving from Melbourne on his doorstep in Oxford, England, where Mark is a student. For years his father had entertained Mark and his two brothers with harrowing accounts of his childhood: how he was the son of Russian pig herders who got lost in a forest, how he was rescued by kindly Latvian soldiers and then adopted by a wealthy family who owned a chocolate factory.

In 1949, when the family immigrated to Australia, they brought him with them. But these were only half-truths, he now tells his son. There is much more, some of it is terrible, and some of it he cannot remember. He is tortured by inchoate memories, he tells him, by wisps of facts.

"I want you to do something for me, son," he says. "I want to know who I am." He wants to learn his real name and his true identity. And he wants to lay a flower on his mother's grave.

To begin with, Alex now tells Mark, he is Jewish, something he has never revealed, even to his wife, a Roman Catholic. He remembers - he was probably 5, but doesn't know his birth date - witnessing Nazi troops shooting his mother and bayoneting his baby brother and sister near their village in Belarus. To keep from screaming, he bit his hand. Believing his father dead, he fled into the forest but was caught - probably by the very soldiers who had murdered his family. They were about to shoot him, he said, when he begged for a piece of bread. One of them pitied him, and he was saved.

It is an anguished tale set in the morally gray zone between culpability and survival. The soldier discovered that the boy was Jewish - he was circumcised - and warned him to hide it. The others thought he was Russian and named him Uldis Kurzemnieks. They made him their mascot, a miniature soldier with a uniform decorated with Nazi insignia. As he traveled with them, he said, he witnessed atrocities, including hundreds of Jews being herded into a synagogue and burned alive. He became a propaganda tool, the Reich's youngest Nazi, the subject of newspaper articles and a documentary.

The soldiers' commander was Karl Lobe, a Latvian police chief later implicated in the murder of thousands of Jews outside Riga. In the 1960s, when Lobe was investigated for war crimes, Alex, pressured by his adoptive family of Nazi sympathizers, signed a statement exonerating him of wrongdoing.

Now the elderly Alex is being punished by both sides, shadowed by Baltic fascists threatening him if he reveals Lobe's deeds and by Holocaust groups investigating him for being a collaborator.

Mark becomes his father's Virgil, guiding him through the underworld of his own past. He begins to dread each new revelation. "Was there something even darker, if that was possible?" he writes.

Father and son journey to Latvia and comb through state archives. As they search out the truth, Mark is torn between filial piety and anger as the old man hesitates, pulls back, terrified to learn more.

At one point, an Oxford historian tells Mark that his father's memories cannot be true. The historian doubts that his father could have survived in the forest and his account of the chronology of events. Perhaps he volunteered to go with the soldiers, he suggests, and is suffering from false-memory syndrome. (Kurzem writes that the Claims Conference in New York, which investigates accounts of Holocaust suffering, doubted his memories, too, but reversed its decision after a Jewish group in Minsk validated them.)

This is a book to keep you up at night. At moments the dialogue seems too smooth to be authentic. Mark, who has produced a documentary about his father, says he compressed events to make his account more readable, and changed some identities to protect people's privacy.

Like a great novel, it culminates in a remarkable scene. Alex Kurzem returns to where his mother, baby brother and sister were murdered. A monument commemorates the 1,600 people buried there in a mass grave. Just as he did the day he saw his mother and siblings standing naked on the edge of a pit and killed, he bites his hand to prevent himself from crying out.

One of the biggest sore spots in Taiwan’s historical friendship with the US came in 1979 when US president Jimmy Carter broke off formal diplomatic relations with Taiwan’s Republic of China (ROC) government so that the US could establish relations with the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Taiwan’s derecognition came purely at China’s insistence, and the US took the deal. Retired American diplomat John Tkacik, who for almost decade surrounding that schism, from 1974 to 1982, worked in embassies in Taipei and Beijing and at the Taiwan Desk in Washington DC, recently argued in the Taipei Times that “President Carter’s derecognition

This year will go down in the history books. Taiwan faces enormous turmoil and uncertainty in the coming months. Which political parties are in a good position to handle big changes? All of the main parties are beset with challenges. Taking stock, this column examined the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) (“Huang Kuo-chang’s choking the life out of the TPP,” May 28, page 12), the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) (“Challenges amid choppy waters for the DPP,” June 14, page 12) and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) (“KMT struggles to seize opportunities as ‘interesting times’ loom,” June 20, page 11). Times like these can

June 23 to June 29 After capturing the walled city of Hsinchu on June 22, 1895, the Japanese hoped to quickly push south and seize control of Taiwan’s entire west coast — but their advance was stalled for more than a month. Not only did local Hakka fighters continue to cause them headaches, resistance forces even attempted to retake the city three times. “We had planned to occupy Anping (Tainan) and Takao (Kaohsiung) as soon as possible, but ever since we took Hsinchu, nearby bandits proclaiming to be ‘righteous people’ (義民) have been destroying train tracks and electrical cables, and gathering in villages

Dr. Y. Tony Yang, Associate Dean of Health Policy and Population Science at George Washington University, argued last week in a piece for the Taipei Times about former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) leading a student delegation to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) that, “The real question is not whether Ma’s visit helps or hurts Taiwan — it is why Taiwan lacks a sophisticated, multi-track approach to one of the most complex geopolitical relationships in the world” (“Ma’s Visit, DPP’s Blind Spot,” June 18, page 8). Yang contends that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has a blind spot: “By treating any