In the small courtyard cellar of the Morgon producer Marcel Lapierre, the barrels are talking. It's the gentle but insistent murmur of the juice of gamay grapes fermenting into Beaujolais wine, the yeast transforming sugar into alcohol and carbon dioxide, which, with no role to play in the finished product, can only hiss its protest at being left behind.

It is not the only hissing here in the Beaujolais, a region long venerated for its bistro wines and now apparently withering on the vine. From the Terres des Pierres Dorees in the south, where the rocks seem to glow a soft gold, to the granite hills of Julienas, Fleurie and the other crus to the north, the talk is of crisis: of rising costs and diminishing returns, of a public that has turned its back on a gentle wine it once embraced, and of a reputation damaged by decades of mediocrity and symbolized by the yawning response to the annual November announcement, "Le Beaujolais nouveau est arrive."

But a different, equally insistent message is also emerging from Beaujolais, and it is a sign of hope for a region that has borne more than its share of condescension and scorn. It comes from the best, most serious producers in Beaujolais, who are making superb wines that bear as much resemblance to mass-market Beaujolais nouveau as a fine, dry-aged steak does to a fast-food burger. In a region known for jolly little knock-back wines to be drunk and forgotten, these are memorable wines of depth and class, thoughtful wines that nonetheless retain the joyous nature imbued in Beaujolais.

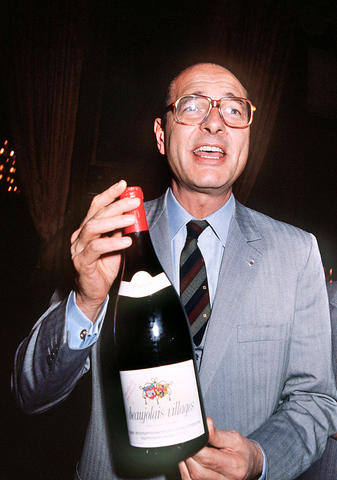

PHOTO: AFP

Few wines can induce joy the way Beaujolais does, and I would argue that that is an undervalued quality. When you add in the perfume and the nuance of the best Beaujolais wines, and combine them with a little bit of structure, you have a wine that deserves far more credit than it gets.

"People think, 'Oh, Beaujolais, it's light, it's fruity,'" said Jacques Lardiere, technical director of Maison Louis Jadot. "But in Moulin-a-Vent you can produce a great wine, a great, great wine."

The idea that Beaujolais can produce great wine is antithetical not only to the image of Beaujolais but also to the notion of what constitutes great wine. Greatness among red wines is generally equated with power, profundity and aging ability.

PHOTO: AFP

Although Beaujolais can sometimes age well - I recently had a delicious 1929 Moulin-a-Vent - it is best enjoyed fairly young. It will never be profound the way Burgundy, Barolo or Bordeaux can be, and notwithstanding young Morgons, which can be tough on tender mouths, Beaujolais tends more toward elegance than power.

Just consider, for example, the purity of those whispering Lapierre Morgons, surprisingly light-bodied and elegant, or the density and balance of a Fleurie from Clos de la Roilette. To taste the fresh yet complex Moulin-a-Vent and Fleurie of Domaine du Vissoux, the pretty, floral Cote de Brouilly of Jean-Paul Brun or the powerful, structured Morgons of Louis-Claude Desvignes is to realize that there is a world of Beaujolais beyond the fatiguingly sappy, candied wines that by comparison taste like tutti-frutti gamay juice.

Great Beaujolais comes in many shapes and sizes. Domaine Cheysson in Chiroubles makes pretty, seductive wines, enticing for their lithe, floral grace. A Julienas from Michel Tete is completely different, spicy, structured and laden with mineral and raspberry flavors. And then there are the dynamic, finely detailed Moulin-a-Vents of Louis Jadot's Chateau des Jacques, like La Roche 2005, smelling of violets and dark fruit, a wine of clarity and finesse.

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

Even among these fine crus, though, it is hard to find a producer who will not talk about what they all call the image problem. And for that they blame Beaujolais nouveau.

"The nouveau has destroyed our image," said Jean-Pierre Large, director of Domaine Cheysson in Chiroubles, as we tasted the fresh, fruity 2007 vintage now resting in cement tanks. He winced as I joked that I was the first to taste his nouveau, which Cheysson does not produce. "All of Beaujolais is confused with nouveau," he said.

The man most responsible for this confusion, of course, is Georges Duboeuf, author of many Beaujolais triumphs. Duboeuf, who grew up in a farm family just outside the Beaujolais region, was already a successful negociant when he began to mass-market the quaint regional autumn custom of celebrating the arrival of the primeur, the year's first wine. The Beaujolais nouveau fashion took off in the 1970s and 1980s. By 1988, some estimates assert, 60 percent of the basic Beaujolais appellation went into primeur.

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

The wine itself may have been a harmless fruity concoction, but its lack of consequence created lasting problems. Growers picked early at minimal ripeness to avoid risks, and compensated by chaptalizing, a legal process of adding sugar to the grape juice to increase the alcohol content, which can result in the impression of artificiality. They would maximize yields, which can dilute the wines, and they would make the wines according to the standardized recipes of the negociants, who bought most of the wine from the growers to be sold under their own labels.

When times were good, nobody much cared. But now that the nouveau fashion has diminished - nouveau is now about 30 percent of Beaujolais production - growers in the lesser regions of Beaujolais are stuck with an oversupply of poor wine. And the public is stuck with an image of insipid wine meant to be drunk immediately.

"Nouveau really contributed to the problems here," said Mathieu Lapierre, who works here with his father, Marcel, farming about 12 hectares of grapes in Morgon. "People overproduced and made really bad wine."

Duboeuf does not see it that way. He says the problems in Beaujolais are similar to those faced all over France, where inexpensive wines have been losing international market share to branded New World wines. Yet Duboeuf is optimistic, and feels the region has taken major steps to right itself, reducing the legal maximum for yields and slowing growth. From 1957, he said, when Beaujolais produced 600,000 hectoliters of wine, to 2000, output had more than doubled to 1.3 million hectoliters, but in two years output will be down to 1 million.

"Growers are making great efforts, and already this year we should be in a more balanced situation," said Duboeuf, still slender and ramrod straight at 74, his hair combed back into a white pompadour, blue cashmere sweater draped over his shoulders. "In two years demand will exceed supply, so prices will go up."

Duboeuf still believes in nouveau. "Japan today is the biggest market for Beaujolais nouveau," he said. "Ten years ago it was nothing. It shows you how things can change in just a few years. There is always potential."

For a mass-market operation, Duboeuf serves up pretty good wine. But it is a world apart from the vignerons making wine from their own fields, in their own cellars, who are not cutting cloth to fit the fashions but are making the wines that they believe in. Most growers are reluctant to criticize Duboeuf, who seems to be held in high esteem, but they do not like to be lumped in with his methods.

Pierre-Marie and Martine Chermette of Domaine du Vissoux are based in St Verand in the southern end of the appellation, but they also own plots in the higher-status crus of Fleurie and Moulin-a-Vent. Doggedly, they keep yields low and scrupulously sort the grapes. They do not chaptalize, they use only the natural yeasts on the grapes rather than specialized yeasts that emphasize particular flavors and aromas, and they use very little sulfur as a stabilizer.

"You can't say we don't have problems," Chermette said, "but we've been at this since 1982, and we've got regular customers and good contacts."

Indeed, the best producers are not the ones who are hurting. Those with a history of making and bottling their own wine, like the Chermettes or like Michel Tete in Julienas, are holding their own. But for those who have depended on supermarket sales and negociants to move their wine, prospects are dimmer.

Growers everywhere like to talk about their old vines and their sustainable agricultural practices, but in the Beaujolais it is not always easy to know how to interpret this talk. Do they have old vines because they have guarded a precious holding? Or is it because they cannot afford to replace ones that have deteriorated? Do they practice sustainable agriculture for philosophical reasons? Or is it because they cannot afford to spray against weeds five times a year?

Against the background of crisis, those who have dedicated themselves to making top-quality wines offer a model for the future. They are the ones who, like Jean-Paul Brun, have taken risks and demonstrated that the public will notice. Brun's estate, Domaine des Terres Dorees, makes wine as naturally as possible, a process that requires great attention.

"You have to select grapes very carefully," he said. "You have to smell, smell, smell, and taste, taste, taste. There's always more risk."

The payoffs are wines of character and depth, and perhaps a public willing to listen to the wines.

"We're selling more and more," he said. "I think people are much more interested in Beaujolais, in the good people, at least."

WARNING: Excessive consumption of alcohol can damage your health.

June 23 to June 29 After capturing the walled city of Hsinchu on June 22, 1895, the Japanese hoped to quickly push south and seize control of Taiwan’s entire west coast — but their advance was stalled for more than a month. Not only did local Hakka fighters continue to cause them headaches, resistance forces even attempted to retake the city three times. “We had planned to occupy Anping (Tainan) and Takao (Kaohsiung) as soon as possible, but ever since we took Hsinchu, nearby bandits proclaiming to be ‘righteous people’ (義民) have been destroying train tracks and electrical cables, and gathering in villages

Dr. Y. Tony Yang, Associate Dean of Health Policy and Population Science at George Washington University, argued last week in a piece for the Taipei Times about former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) leading a student delegation to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) that, “The real question is not whether Ma’s visit helps or hurts Taiwan — it is why Taiwan lacks a sophisticated, multi-track approach to one of the most complex geopolitical relationships in the world” (“Ma’s Visit, DPP’s Blind Spot,” June 18, page 8). Yang contends that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has a blind spot: “By treating any

Swooping low over the banks of a Nile River tributary, an aid flight run by retired American military officers released a stream of food-stuffed sacks over a town emptied by fighting in South Sudan, a country wracked by conflict. Last week’s air drop was the latest in a controversial development — private contracting firms led by former US intelligence officers and military veterans delivering aid to some of the world’s deadliest conflict zones, in operations organized with governments that are combatants in the conflicts. The moves are roiling the global aid community, which warns of a more militarized, politicized and profit-seeking trend

This year will go down in the history books. Taiwan faces enormous turmoil and uncertainty in the coming months. Which political parties are in a good position to handle big changes? All of the main parties are beset with challenges. Taking stock, this column examined the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) (“Huang Kuo-chang’s choking the life out of the TPP,” May 28, page 12), the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) (“Challenges amid choppy waters for the DPP,” June 14, page 12) and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) (“KMT struggles to seize opportunities as ‘interesting times’ loom,” June 20, page 11). Times like these can