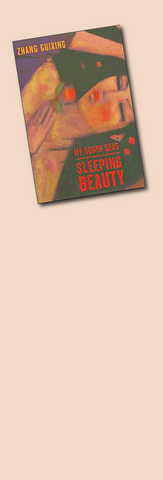

My South Seas Sleeping Beauty (我思念的長眠中的南國公主) marks the English-language debut of Taiwan-Malaysian novelist Zhang Guixing (張貴興). It goes, as it were, directly to the Number One slot, appearing in Columbia's Modern Chinese Literature from Taiwan series, currently 14 titles strong. In Valerie Jaffee's superb translation into idiomatic yet eloquent English, this colorful and intriguing novel effortlessly justifies its new-found status.

The book was published in Chinese in 2001, and like most of Zhang's novels is set in Malaysia's North Borneo, formerly Sarawak, where the author was born in 1956. It's an ultra-exotic world of crocodiles with wrist-watches in their bellies, giant bats, hot-air balloons, owls knocking wine-glasses from the hands of party-goers, dogfights that are a cover for orgies with pubescent Dayak girls, and vegetation and weather that are replete with luxuriant sexual imagery whatever the El Nino-twisted season.

Everyone writing about Zhang invokes the South American magic realism of Garcia Marquez. Magic realism arguably stems from increasing globalization and the decline of local individuality. With belief in spirits declining (though not in Taiwan) and endangered species drifting towards extinction (tragically still the case here), it re-ignites the world of the exotic and the strange. What may no longer be there in life is alive and well in the imagination, as indeed it has always been.

The narrator, Su Qi, is the young son of affluent Chinese settlers. The family lives within sight of the river dividing Malaysia and Brunei, something the boy watches though binoculars from his tree-house. He sees a lot else as well — tigers in the grass, Communist insurgents, and most notably the infatuation of both his parents with non-Chinese locals. His mother bears a son by a Dayak lover, while his father is enchanted by a woman in white sent by the forest-based Communists to extort money from the Chinese bourgeoisie.

Central to the story is a garden, lovingly tended by Su's mother but in reality little different from the riotous jungle that surrounds it. It quickly becomes a version of the Garden of Eden, and a place that tempts a guilt-free sexuality to flourish. The Bible-gripping mother and the shot-gun-toting father — together with a pipe-smoking neighbor adept with an electric cattle-prod with which he herds 14-year-old Dayak girls who he persuades to act as "maids" — are all trying, and failing, to resist the lure of the primitive and the unrestrained. Sex is everywhere in nature, including their own human nature, and as they try to fight it with violence and recriminations, these in reality alternate with wild parties attended both by a Brunei prince in disguise and Communist insurgents posing as government ministers.

Storms and fires inevitably erupt, mocking the strutting and moralizing humans, while tigers roar in the overgrown garden and bees assault the drunken revelers.

But this extraordinary world alternates with a sedate version of 1970s Taipei where the narrator goes (following in the novelist's own footsteps) to study European literature. There he meets a beautiful folk-singer and fellow student from Tainan called Keyi. She's had an abused childhood, attracting the attentions of both men and women, something that both parallels and contrasts with the freewheeling world Su Qi has known. And Taipei too is presented in marked contrast to Borneo. There is almost no local detail offered, just the narrator's daily travels from home to coffee shops, and to clubs where Keyi is singing.

But there's more to the story than this. Su Qi is enthralled by his mother's breasts — she breast-fed him to the age of 10 — and by the mystique of her beloved garden. He may have witnessed horrors such as the death of his infant sister, but he is essentially a child of nature. A string of women are drawn to him, but he shows little real interest, and even responds to Keyi's advances with a kind of casual acquiescence. Whatever else he may be, he is also the classic literary loner, observing the world rather than becoming overly involved in it.

And this is a very literary book. A near-contemporary exoticism is contrasted with an older one, the Asia drawn by Maugham, Conrad, Kipling and Chinese novelist Yu Dafu (郁達夫) (all mentioned). The narrator records tapes of classic modern novels and sends them to his girlfriends, and casually includes criticism of the "instability and monstrosity" of Mishima's writing. He meets Keyi in a Taipei coffee shop where they can order Henry James black tea (indistinguishable from George Sand black tea) and eat Pearl S. Buck strawberry cake.

This is a gripping as well as a probing book. At times it reads like the intelligent man's Harry Potter. Maybe Zhang has failed to distance himself sufficiently from his own childhood (though who can tell?) — but even if he has it doesn't matter. Creative inventiveness has never been imperative, and writers from Shakespeare to Hardy have either bought their plots or freely adapted other people's. The alternative of investing your own life-story with mythic dimensions, popular from Proust to Kerouac, has now itself acquired a long history.

My South Seas Sleeping Beauty in fact exhibits abundant ingenuity. The narrator is drawn, for instance, to his Borneo neighbor's daughter, but can't distinguish her from her twin sister. The author seizes the opportunity to revel in some of the narrative possibilities identical twins suggest, from substituting for each other at school, in college entrance exams, and even in their boyfriend's bed.

It's because Zhang (currently teaching English in a Taipei high-school) is equally at home with ideas and the more flamboyant aspects of reality that this book is so successful. Death by poisoned arrows and young girls electrically charged so that they glow when they walk past a stereo alternate with literary criticism and nutritional ideas about mother's milk. This wonderful novel is a lot more than Marquez relocated in Sarawak, and after reading it reports of forest fires in Borneo will never sound quite the same again.

This is the year that the demographic crisis will begin to impact people’s lives. This will create pressures on treatment and hiring of foreigners. Regardless of whatever technological breakthroughs happen, the real value will come from digesting and productively applying existing technologies in new and creative ways. INTRODUCING BASIC SERVICES BREAKDOWNS At some point soon, we will begin to witness a breakdown in basic services. Initially, it will be limited and sporadic, but the frequency and newsworthiness of the incidents will only continue to accelerate dramatically in the coming years. Here in central Taiwan, many basic services are severely understaffed, and

Jan. 5 to Jan. 11 Of the more than 3,000km of sugar railway that once criss-crossed central and southern Taiwan, just 16.1km remain in operation today. By the time Dafydd Fell began photographing the network in earnest in 1994, it was already well past its heyday. The system had been significantly cut back, leaving behind abandoned stations, rusting rolling stock and crumbling facilities. This reduction continued during the five years of his documentation, adding urgency to his task. As passenger services had already ceased by then, Fell had to wait for the sugarcane harvest season each year, which typically ran from

It is a soulful folk song, filled with feeling and history: A love-stricken young man tells God about his hopes and dreams of happiness. Generations of Uighurs, the Turkic ethnic minority in China’s Xinjiang region, have played it at parties and weddings. But today, if they download it, play it or share it online, they risk ending up in prison. Besh pede, a popular Uighur folk ballad, is among dozens of Uighur-language songs that have been deemed “problematic” by Xinjiang authorities, according to a recording of a meeting held by police and other local officials in the historic city of Kashgar in

It’s a good thing that 2025 is over. Yes, I fully expect we will look back on the year with nostalgia, once we have experienced this year and 2027. Traditionally at New Years much discourse is devoted to discussing what happened the previous year. Let’s have a look at what didn’t happen. Many bad things did not happen. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) did not attack Taiwan. We didn’t have a massive, destructive earthquake or drought. We didn’t have a major human pandemic. No widespread unemployment or other destructive social events. Nothing serious was done about Taiwan’s swelling birth rate catastrophe.