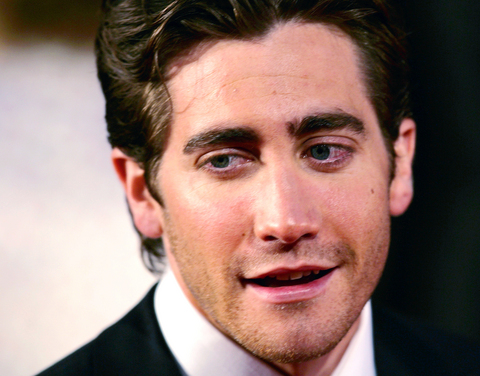

For a while last year, Jake Gyllenhaal was everywhere and the issues demanding his commentary were numerous: there was the war in Iraq, which he took on when Jarhead, set in the first Gulf war, was launched; there was the meaning of genius (via Proof); homophobia in rural America (Brokeback Mountain); and — harking back to his role in the 2004 disaster movie The Day After Tomorrow — that hardy perennial of the politically engaged actor, global warming. When Gyllenhaal wasn't addressing the major issues of the day, his sister, Maggie, was giving it all she had on the state of the world post-9/11, thanks to her appearance in the film World Trade Center. Some days it felt as if there simply weren't enough issues out there to keep the Gyllenhaal siblings in serviceable opinions.

Theirs is a classic liberal Hollywood family: father, Stephen, a director, mother, Naomi, a screenwriter, and two children who started acting in their school days. Gyllenhaal's first professional role was at the age of 10, playing Billy Crystal's son in City Slickers, and after that his parents had him turn down lots of roles so that he could concentrate on his school work. At 19, he took his first lead, in a film called October Sky — "The true story of a coal miner's son who was inspired by the first Sputnik launch to take up rocketry, against his father's wishes" — and since then he has become the go-to guy for any film requiring brooding sensitivity with just enough geekiness to inject a bit of comedy. Gyllenhaal is in London to present an award at the Baftas, having won one himself last year. He is also promoting a new film, Zodiac, a straightforward serial-killer flick, co-starring Mark Ruffalo and Robert Downey Jr. It's based on a memoir by Robert Graysmith, a cartoonist at the San Francisco Chronicle in the 1970s, who took it upon himself to investigate a serial killer who was terrorizing the city under the pseudonym the Zodiac. Graysmith became so obsessed by the case that he took on shadow characteristics of the killer himself, so much so that Gyllenhaal was nervous about meeting him. "It wasn't the cosiest idea," he says. "What sort of guy 'gets into' a serial killer?"

The result is an enjoyable cop film, and the three male leads, including Downey Jr as the twitching, alcoholic chief crime reporter, are a pleasure to watch. I assume Gyllenhaal was glad to get off the issue-laden conveyor belt of his previous few films, but, he says, "Strangely, I like talking about all that." Politics was always a part of the household he grew up in and today Gyllenhaal reads the domestic and foreign papers online and is an obsessive keeper of pieces from the New York Times. His studenty earnestness is undercut, here and there, by a dim awareness that people don't like being lectured by actors, and he'll round off a speech against the war in Iraq with a little what-do-I-know shrug. He is passionate and well-informed and in 10 years' time he could be George Clooney; then again, he could be Sean Penn.

PHOTOS: AGENCIES

At 27 he is still as serious-minded as a teenager, determined to root out the underlying issues in all things. "Well, I actually believe that this film [Zodiac] is — you're probably going to look at me like I'm a madman — but I think it's about the advent of the cellphone. It would be a 25-minute movie if there were cellphones in the 70s. Because all the things that go wrong, if there had been a means of communication on your person that had been as quick as text message or a phone call, I think they could've solved this. This movie is a lot about the lack of technology."

I suppose I must be looking at him like he's a madman, because he adds, "But it's nice just to talk about serial killers."

It was Donnie Darko that first brought Gyllenhaal to a wider audience, and what brought him to Donnie Darko was, in a roundabout way, Buddhism. After leaving school, he flew to the other side of the country to attend Columbia University in New York. Maggie, three years his senior, was already there and together they took a class called Introduction To Tibetan Buddhism. "I had read some books that my mom gave me, those be-where-you-are-now kind of books, and slowly found myself interested in what that was about. I think Buddhism is extraordinary. I also think that religion in general, organized or not in its conception, is extraordinary. I love the ideas. I believe in most of them intuitively. We were all talking about 'chi' last night, and energy, and a lot of people pass off all this bullshit about it, and I do half the time, too, and then I realized that there's something inherent in me that believes in the energy between people. And the energy in myself. And that's just a law. That's a meaning. It doesn't falter. It's not something that's been created by us, it literally exists. That I find fascinating, and I think that's what drew me to Buddhism."

Donnie Darko is either very deep or completely meaningless; it's hard to tell, but in any case it has a large cult following and many Web sites devoted to analyzing its import. (If you've never seen it, it's the story of a teenage boy who has lucid dreams of a tangential universe that highlight the ultimate paradox of existence, or something along those lines.) Through his studies in eastern religion, Gyllenhaal was drawn to the script and it reignited his enthusiasm for acting, which had begun to wane. He dropped out of Columbia after two years, even though he'd done most of the hard work by then and was getting "the best grades of my life." But he felt creatively understimulated, and "I wasn't happy only using my intellect. I've grown more confident in the idea that the more I use my intellect, the less happy I am."

Gyllenhaal is very good as Donnie Darko, as he is as Robert Graysmith, and both are characters who exist on the border between creepy and cute. I think this has something to do with his talent as a comedian. When he isn't talking about Buddhism, there is an air of self-deprecating likability about Gyllenhaal that is aided by the fact that he looks, from certain angles, like a benign version of the Joker in Batman.

He is surprisingly ambivalent about acting. In 1989, while he was gearing up to play his first role, his mother was nominated for an Oscar for her screenplay of Running On Empty, and Gyllenhaal is keenly aware of the downside to having film-maker parents. "Probably you struggle a bit," he says, "when your family is making movies and when your father's a director and your mother's a writer, there's a constant — even for a couple of months as a young child, to have your parents' focus somewhere else is ... there's always a little bit of a struggle. I watch children now and see how impactful small things are."

The problem is one of attention: part of the reason he lobbied his parents to let him act as a child was that he wanted to command more of their interest. "I think there is definitely a bit of a double edge ... . I think there are kids who are put into it because their parents want something from them, or they're using them, without even knowing it on a conscious level. Mine is a complicated one in that some people do it out of actual pure love for it, and then there's, like, the ... . I think ultimately the reason why I do it is because I wanted to be a part of [my parents' world]."

Well, I say, it's lucky for you that you were any good at it. "It's funny, 'cos I was [always introduced as] 'Maggie's little brother' and I was like, 'No, I'm not.' But I am." The drawback to starting work so young, he implies, is that you make a decision that shapes your whole life, at a time when you shouldn't be making decisions bigger than chocolate or strawberry. It has left him bemused about his life and what he should be doing with it. "Why did I do it? Why did I start so young?" he says vaguely. "Yes, that is the question." Does he ever wonder whether acting might not be what he ultimately ends up doing? "I still think about that every day."

His options are broadened by the other part of his upbringing; the pervasive social conscience and the belief his parents had in exposing their children to a wide range of views and experiences. To offset the ritziness of their Hollywood lifestyle, Gyllenhaal's parents made sure he saw another side of life. He spent the day of his bar mitzvah volunteering at a homeless shelter. In adulthood, he has gravitated towards playing messy or marginalized people. In The Good Girl, a much underrated film with Jennifer Aniston, he sent up the post-Holden Caulfield cliche of disaffected American youth; in Jarhead, Sam Mendes' film about a squad of marines kicking their heels waiting for war, he played the sniper Anthony Swofford. Playing real people is problematic, but at least with Swofford and Homer Hickam in October Sky, "There was a sense that they had come to terms with the story they have told."

He didn't get this sense from Graysmith at all, who still gave him the creeps, despite being an ostensibly nice guy. "He was the sweetest, kindest and most unassuming man. He sat down and said, 'I'm a really big fan, I'm so happy you're playing me.' I was like, thanks." But then, "Occasionally he would glance at things on me, and I'd think, what's he looking at? And he'd say things like, 'I like your shoes. Where did you get them? I had a pair of shoes like that once. What store did you get them from?' And then about an hour into it I realized if I didn't answer a question that he wanted an answer for, he would just throw it back in a different way. He was incessant, almost an obsessive journalist. He wouldn't let things lie."

It wasn't Graysmith's job to track the serial killer, it was "just his interest. And I wanted to know where the interest came from. Everyone said, when you meet Robert, you'll understand. And then I met him and I realized: he actually found joyed in it."

Gyllenhaal lives in New York. He used to go out with Kirsten Dunst. He keeps a journal and might explore writing more in the future. He and his sister Maggie don't talk much about their jobs, only when one or other of them is stuck; it is important, he says, for him to be "a good brother" to her. He is excited about the forthcoming US elections, but hasn't yet decided between Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama. "It's good to think of the prospects of a woman or someone of a different race being president of the US." He has learned to tell people "that I'm Canadian when I go to foreign countries." He is a little afraid that there is not enough separation between the Democrats and Republicans to make much of a difference. He wishes politicians would talk more plainly, so that you didn't have to guess what they were trying to say.

"I see politicians struggle as I see other actors struggle. Actors and politicians share a lot of similarities. And it's a sad time when politicians have to act. I feel like when you appeal to everybody, it may seem that everybody likes you, but is that really who you are? The ability to be human is to have people like you or not like you. But when you're in the job of getting votes, it's, like, who are you gonna be?"

April 28 to May 4 During the Japanese colonial era, a city’s “first” high school typically served Japanese students, while Taiwanese attended the “second” high school. Only in Taichung was this reversed. That’s because when Taichung First High School opened its doors on May 1, 1915 to serve Taiwanese students who were previously barred from secondary education, it was the only high school in town. Former principal Hideo Azukisawa threatened to quit when the government in 1922 attempted to transfer the “first” designation to a new local high school for Japanese students, leading to this unusual situation. Prior to the Taichung First

The Ministry of Education last month proposed a nationwide ban on mobile devices in schools, aiming to curb concerns over student phone addiction. Under the revised regulation, which will take effect in August, teachers and schools will be required to collect mobile devices — including phones, laptops and wearables devices — for safekeeping during school hours, unless they are being used for educational purposes. For Chang Fong-ching (張鳳琴), the ban will have a positive impact. “It’s a good move,” says the professor in the department of

On April 17, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) launched a bold campaign to revive and revitalize the KMT base by calling for an impromptu rally at the Taipei prosecutor’s offices to protest recent arrests of KMT recall campaigners over allegations of forgery and fraud involving signatures of dead voters. The protest had no time to apply for permits and was illegal, but that played into the sense of opposition grievance at alleged weaponization of the judiciary by the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) to “annihilate” the opposition parties. Blamed for faltering recall campaigns and faced with a KMT chair

Article 2 of the Additional Articles of the Constitution of the Republic of China (中華民國憲法增修條文) stipulates that upon a vote of no confidence in the premier, the president can dissolve the legislature within 10 days. If the legislature is dissolved, a new legislative election must be held within 60 days, and the legislators’ terms will then be reckoned from that election. Two weeks ago Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (蔣萬安) of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) proposed that the legislature hold a vote of no confidence in the premier and dare the president to dissolve the legislature. The legislature is currently controlled