It can seriously damage your health, being a guru. When Dr. Atkins, he of the "wonder" diet, tripped and died it emerged he was suffering from heart disease. He followed on the heels of Jim Fixx, jogging guru, who gasped his last while running. And what of Jerome Rodale? The prize turnip in the organic farming movement slumped forward in his chair while on a chat show. "Are we boring you?" inquired the host. Alas, we will never know; Rodale had chomped his last carrot.

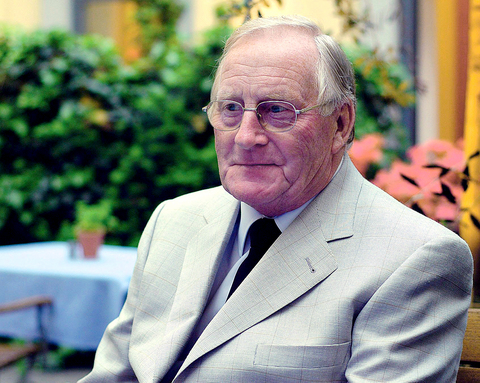

Last month Allen Carr, the world's leading anti-smoking Svengali, died of lung cancer. Colleagues blamed years of passive smoking while helping folk stub out the evil weed. I was probably the last journalist to meet Carr, at his Surrey home in southern England a few months before his death. For a man of his wealth — clinics in 30 countries, books translated into 45 languages — he hardly whooped it up in the lap of luxury. His modest terrace house sat primly in a drab estate. As his wife served biscuits on a doily, the man who claimed to have helped 10 million smokers give up wheezed in.

He was one of the world's best-selling authors, but this bespectacled figure looked like the accountant he was when, on 15 July 1983 — "independence day" — the 100-a-day puffer hit on a method to give up. Actually it is more mantra than method: cigarettes are not a positive, so their absence should not be mourned. It sounds simple — banal, even — yet Carr could talk comfortably for four hours about his theory. One woman he helped quit sighs: "He bored me into giving up." Boring works: Carr claimed that over half who visited his clinics were cured (including Richard Branson and Anthony Hopkins).

PHOTO: EPA

The man who modestly compared himself to Galileo prepared to enter that great no-smoking lounge in the sky with the same remorseless positivity that made him a guru.

Crusading until the last

By the time I met him, cancer had spread to the lymph gland. Doctors had given him nine months to live, overly optimistic as it turned out. His last wish was to persuade the UK health service to provide his anti-smoking cure. Ever the businessman, he offered to charge the health service for treating people, with money back guarantees for those who continued to smoke.

He was remarkably sanguine for one who had just seen his last summer. He even made assisted suicide — which he disclosed he was considering — sound like a cross-Channel ferry jaunt. "If it gets really bad, I would probably nip over to Holland, where I gather they do euthanasia. I used to hate going to the dentist and I imagine it will not be any worse than that," he said.

Joyce, the devoted second Mrs. Carr, swung her head round the door offering more tea. Once she had gone, he leaned forward and said: "We have discussed assisted suicide and she does not want me to do it."

Joyce was with him when he had his Eureka anti-smoking moment. "I stubbed out my last, saying, 'I'm going to cure the world of smoking.' Joyce thought I'd flipped. She'd seen umpteen attempts. The previous one ended in me sobbing like a baby." He had even broken a vow to his father — made on his father's deathbed, before he died of cancer — that he would give up. "I went straight outside and lit up," Carr recalls. "That was its power."

When he finally conquered his addiction, he assumed the certainty of all evangelists. "I thought smoking would be quickly reduced to the level of snuff-taking, but I wrote to Edwina Currie [then UK Health Minister] and the Lancet medical journal and was ignored; I was treated like a nut." He sounded surprised — outraged, even — but Carr had no expertise and had not submitted his method to trials.

On to a winner

Yet he called his technique scientific and rated it highly. "It was only by the grace of God I found the method," he said, eyes clear of doubt. "It is like being the Count of Monte Cristo stuck in a dungeon all your life, suddenly finding yourself outside ... ." Still, our count began seeing patients in his front room in Raynes Park, south-west London. "We had no money, but our reputation spread." The only cowpats were rumors that he puffed secretly. One such rumor cost the British DJ Chris Evans a ?100,000 (NT$6.3 million) libel bill. "Allen Carr is under the spotlight every day," Carr said. "I would have been caught. One lie would bring the entire house down."

The surprise, I suggested, is that after years of health warnings people persist in smoking. "You know what profession comes to my clinics the most? Doctors and nurses." They and tobacco executives. "I have had loads of Marlboro men, including two directors. I thought they had come to assassinate me," he laughed. Carr was against bans and any hint of nanny-statedom: "Prohibition didn't work. You don't need to ban it if you educate people." Schools, of course, try the demonization theory and it doesn't work. "I would explain the trap: the first cigarette tastes so bad no one thinks they will be hooked, but they are." And cigarettes, he suggested, are worse than heroin because of the numbers killed: "It is a poison: if you inject nicotine of one cigarette into a vein, it could kill you."

Joyce carted in boxes of letters from grateful patients who had heard of his cancer and offered sympathy. But he had no time to read them — too busy writing his last will and testament, Scandal, exposing a conspiracy he believes links ministers and tobacco companies.

So I said goodbye to a man who may have been at the fag end of his life, but you would never know it: never had I met anyone so cheerful about meeting the Grim Reaper. And never had I met a man so ordinary who had saved the lives of so many.

On the Net: A copy of Allen Carr's Scandal can be downloaded free of charge from www.allencarr.com

June 23 to June 29 After capturing the walled city of Hsinchu on June 22, 1895, the Japanese hoped to quickly push south and seize control of Taiwan’s entire west coast — but their advance was stalled for more than a month. Not only did local Hakka fighters continue to cause them headaches, resistance forces even attempted to retake the city three times. “We had planned to occupy Anping (Tainan) and Takao (Kaohsiung) as soon as possible, but ever since we took Hsinchu, nearby bandits proclaiming to be ‘righteous people’ (義民) have been destroying train tracks and electrical cables, and gathering in villages

Dr. Y. Tony Yang, Associate Dean of Health Policy and Population Science at George Washington University, argued last week in a piece for the Taipei Times about former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) leading a student delegation to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) that, “The real question is not whether Ma’s visit helps or hurts Taiwan — it is why Taiwan lacks a sophisticated, multi-track approach to one of the most complex geopolitical relationships in the world” (“Ma’s Visit, DPP’s Blind Spot,” June 18, page 8). Yang contends that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has a blind spot: “By treating any

Swooping low over the banks of a Nile River tributary, an aid flight run by retired American military officers released a stream of food-stuffed sacks over a town emptied by fighting in South Sudan, a country wracked by conflict. Last week’s air drop was the latest in a controversial development — private contracting firms led by former US intelligence officers and military veterans delivering aid to some of the world’s deadliest conflict zones, in operations organized with governments that are combatants in the conflicts. The moves are roiling the global aid community, which warns of a more militarized, politicized and profit-seeking trend

This year will go down in the history books. Taiwan faces enormous turmoil and uncertainty in the coming months. Which political parties are in a good position to handle big changes? All of the main parties are beset with challenges. Taking stock, this column examined the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) (“Huang Kuo-chang’s choking the life out of the TPP,” May 28, page 12), the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) (“Challenges amid choppy waters for the DPP,” June 14, page 12) and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) (“KMT struggles to seize opportunities as ‘interesting times’ loom,” June 20, page 11). Times like these can