The largest skateboard ramp in the world can be found on a 4.9-hectare farm north of San Diego among the green foothills of the San Marcos Mountains.

Pilots routinely adjust their flight paths for a closer look, which is as good a way as any to sum up the scale of the Mega Ramp. The wooden structure is longer than a football field, as tall as an eight-story building, with a creek bed running through a 21m breach.

On a recent sunny afternoon, the ramp's owner, Bob Burnquist, a renowned 30-year-old professional skateboarder from Brazil, peered over the side to treetops below and said: "I'm not afraid of falling. I'm afraid I might jump."

PHOTOS: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

That mind-set helps on the Mega Ramp, where skaters reach speeds of up to 88kph and soar like stuntmen.

Approximately 110m long, the ramp is 23m high at its apex. That is where riders begin their run, speeding down a 55m-long roll-in to a ramp that launches them across a 21m gap with trapeze netting below. Landing on an 8m sloped section, they then boost up to 15m above the ground from a 9m quarterpipe. A shorter route begins with a 17m-tall platform leading to a 15m gap, and the 9m quarterpipe.

For Burnquist, who stands out in a crowd of iconoclasts, the ramp has become the latest step in a journey to create what he called an exponential progression in an otherwise mostly streetbound, terrestrial sport.

Completed in September after more than a year of construction, Burnquist's Mega Ramp cost US$280,000, part of which was covered by his apparel sponsors Oakley and Hurley. Although not the first — the X Games builds one each year — it is the world's only permanent Mega Ramp, and Burnquist said having it at his home allows him to explore all the possibilities of the sport's most daring discipline.

"Bob has this ability that transcends traditional vert skating," Tony Hawk, the sport's biggest icon, said of ramp skateboarding. "He can spin like no one else spins. He's comfortable upside down. He's the only one that can actually start backwards on the Mega Ramp."

A winner of 12 medals at the X Games, Burnquist performs moves no one else dares try: he has rolled upside down through a Hot Wheels-style loop — backward. And in March he built a 12m-tall ramp on the rim of the Grand Canyon, from which he launched himself and his skateboard onto a makeshift metal rail, and then BASE jumped 487m to the canyon floor below. BASE is the acronym for using a parachute to jump from fixed objects of a building, antenna, span, earth.

"When I'm risk-taking I feel like I'm alive," said Burnquist, who is also a farmer, pilot, skydiver, musician and restaurateur.

"I trip out on how his mind works," said his partner Jen O'Brien, a professional skateboarder herself. "The wheels are always turning."

Building a structure of the Mega Ramp's size in an agricultural district required a creative twist typical of Burnquist.

"I've done some organic farming and I plan on doing some more," he said, explaining how he skirted zoning restrictions. "In the conservation plan, the ramps are the agricultural buildings. I'll put some plastic on the side and build a greenhouse underneath. That way it is proven it's an ag building and I happen to skate on the roof."

The only visitor to ride so far has been professional skater and Mega Ramp pioneer Danny Way, Burnquist's lifelong muse.

Not wanting to risk injury, other elite skaters have been waiting for the end of the competition season. But beginning next month and continuing through the winter, many of them will descend on Burnquist's backyard.

The Mega Ramp is the latest backyard creation, adding to an ensemble that includes a 4m-tall ramp with a clamshell shape appended to one end; a loop-the-loop with a removable top; a 3.6m diameter metal pipe; and a corkscrew design that requires an inverted leap from one section to the other.

"It's like a paradise for skaters," said Sandro Dias, a professional who is also from Brazil. "It's a playground for us."

Burnquist lives among his creations in a spacious two-story stucco house with O'Brien and their six-year-old daughter, Lotus. Their menagerie includes two goats, six chickens, two dogs, a cat, a rabbit and a turtle.

Last week the Burnquist homestead was a locus for family and friends from Brazil, and industry filmmakers and photographers.

Born in Rio de Janeiro — reared in Sao Paolo — to an American father and Brazilian mother, Burnquist grew up speaking English and Portuguese.

He began skateboarding at 11, and developed a unique style by imitating the exploits of professionals featured in magazines and videos. He was particularly captivated by Way, then a teen prodigy from California.

Way had experimented with performing tricks switch-stance; standing the opposite way on the board, like switch-hitting in baseball.

But Burnquist took switch-stance further, learning a full repertory of tricks. Still, he remained unknown in the US until the skateboarding magazine Thrasher led a group of American professionals to Brazil in April 1994. Because he could speak English, Burnquist offered to act as translator and guide.

"He was a dirty skate rat dude with two different shoes on," the Thrasher editor Jake Phelps said. "He just followed us around."

But Burnquist, then 17, impressed them with his skating.

"I knew he was doing stuff that was light years ahead of what people were doing then, Phillips said. "With his switch riding, he had a go for it mentality — 'Make it, or take me to the hospital.'"

The next year Burnquist won his first contest against top international competition, and his star rose quickly. Lanky at 188cm, with trademark thick, black-framed glasses, he became an international skateboarding celebrity and a pitchman for the likes of Lego and the Got Milk? campaign. In Brazil, his popularity comes after that of soccer stars, Dias said.

All of which allowed him to buy a former horse ranch in Southern California in 1999 and indulge his restless imagination by building ramps.

He did not invent the Mega Ramp, however. Way conceived and built the first — a temporary structure — in 2002 at an airport near the Mexican border.

The X Games added a Mega Ramp in 2004 for its Big Air discipline. Then, last year, Way used a Mega Ramp to launch over a 22m wide section of the Great Wall of China.

Only two dozen skaters in the world have the skill and guts to ride such a ramp. Way has been the leader, winning three consecutive gold medals at the X Games. At the last Games in August, Burnquist won the bronze medal.

"The amount of willing participants is always going to be a select few," said Hawk, who has ridden the ramp. "It takes a certain person to want to do it. I know plenty of guys who did it once and said, 'I'm done.' Knowing you've done it is an accomplishment in and of itself."

"If something goes bad it could be a tragedy," Hawk said. "It's not like you blow out your knee. You could fall 15m."

The professional Brian Patch fractured several bones in his left foot when he fell 4.6m to the deck of the quarterpipe at the X Games.

"If you go down here you're going to get broken," Burnquist said.

He has fallen hard and rolled his ankle, but sustained no breaks. To protect himself, Burnquist wears pads on his hip, tailbone, ribs, elbows and knees. He also wears a helmet and knee braces. All skin, except for his face, is covered by neoprene to prevent severe friction burns. He can wear through a pair of sneakers and gloves each session from sliding on the ramp's surface during wipeouts.

Although Burnquist said he felt scared riding his ramp, he did not appear so on a first run during a solo session recently.

Rolling in from the lower platform, he shot over the gap, spun a 360o mute grab, touched down and zipped toward the quarterpipe before floating into an elegant method air more than 12m up. Landing cleanly, he rolled away.

Afterward he walked off the ramp, plopped into the passenger's seat of a golf cart and was ferried 91m uphill. At the top he climbed two sets of stairs to the platform and set up for another run.

Alone at the pinnacle of skateboarding's newest discipline, the sky was the limit.

On a harsh winter afternoon last month, 2,000 protesters marched and chanted slogans such as “CCP out” and “Korea for Koreans” in Seoul’s popular Gangnam District. Participants — mostly students — wore caps printed with the Chinese characters for “exterminate communism” (滅共) and held banners reading “Heaven will destroy the Chinese Communist Party” (天滅中共). During the march, Park Jun-young, the leader of the protest organizer “Free University,” a conservative youth movement, who was on a hunger strike, collapsed after delivering a speech in sub-zero temperatures and was later hospitalized. Several protesters shaved their heads at the end of the demonstration. A

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of

In August of 1949 American journalist Darrell Berrigan toured occupied Formosa and on Aug. 13 published “Should We Grab Formosa?” in the Saturday Evening Post. Berrigan, cataloguing the numerous horrors of corruption and looting the occupying Republic of China (ROC) was inflicting on the locals, advocated outright annexation of Taiwan by the US. He contended the islanders would welcome that. Berrigan also observed that the islanders were planning another revolt, and wrote of their “island nationalism.” The US position on Taiwan was well known there, and islanders, he said, had told him of US official statements that Taiwan had not

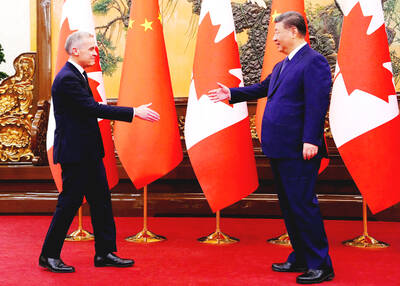

Britain’s Keir Starmer is the latest Western leader to thaw trade ties with China in a shift analysts say is driven by US tariff pressure and unease over US President Donald Trump’s volatile policy playbook. The prime minister’s Beijing visit this week to promote “pragmatic” co-operation comes on the heels of advances from the leaders of Canada, Ireland, France and Finland. Most were making the trip for the first time in years to refresh their partnership with the world’s second-largest economy. “There is a veritable race among European heads of government to meet with (Chinese leader) Xi Jinping (習近平),” said Hosuk Lee-Makiyama, director