It's Friday night at the Confraria das Artes, one of the hippest nightclubs in Brazil, and the crowded patio looks like a fashion shoot set in an antique store. Reclining on vintage couches and creaking rocking chairs under Moroccan chandeliers, dozens of long-limbed, honey-skinned blondes are sipping caipirinhas and flirting with tanned men in muscle shirts.

Supermodels Gisele Bundchen, Mariana Weickert and Alessandra Ambrosio are known to frequent the Confraria, as is local tennis star Gustavo Kuerten. Keen to discover who's who, I ask our waiter, Rogerio, a dashing 20-something surfer dude, to point out the bar's stars. But Rogerio is of no use.

"I don't know any of them," he shouts over the ambient dance track. "I just took this job to earn some money so I could surf all day. A few years ago no one cared anything about Floripa. But now it's gone crazy!"

If a local like Rogerio is disoriented, imagine how I feel. I thought I knew something about hip Brazil -- the chic resorts of Angra dos Reis, Buzios and Parati, where the likes of Mick Jagger, Naomi Campbell and Ronaldo hang out. But when a Brazilian friend in London told me that the hottest place in the country -- and the new Punta del Este of South America -- was an island city in the south called Florianopolis, I almost laughed. Floria what? It sounded like a Greek island. Or a brand of toothpaste. If it was so popular, why hadn't we heard of it? Turns out millions of South Americans have -- but they've been keeping it to themselves.

An hour's flight from Sao Paulo, not far from the border with Uruguay, Floripa, as it's known to locals, is the capital of Santa Catarina state. It lies on a gorgeous 483km2 island made up of 17th-century fishing villages, jungle-covered hills,

emerald lagoons and more than 40 pristine white sand beaches. Flying in from Sao Paulo, it looks like tropical paradise. Put a volcano on those hills, and it could be Hawaii.

Linked to the mainland by a single suspension bridge, for many years Floripa was -- like the rest of Santa Catarina -- a rural idyll.

But in the past five years, the island's popularity has exploded. As crime rates in Sao Paulo and Rio soared, wealthy urbanites snapped up homes on its beachfronts and opened restaurants, clubs and bars on its lagoon shores. In 2002, it was said Florianopolis was the best and safest place to live in Brazil. Today, more Brazilian and South American tourists head to Floripa on their December breaks than anywhere else in the country except for Rio. And in summer the regular population of 330,000 swells to more than 1 million.

They come for the beaches, the surfing, the snorkelling, the seafood and, of course, to party like only South Americans know how.

Setting the scene

If Floripa is a potential Punta del Este, the center of the "scene" is Lagoa da Conceicao, a village set around the main lagoon in the heart of the island, beneath the wooded hills. Kite surfers skim the glassy water, dodging wooden boats ferrying tourists to seafood restaurants on the far shores, and the sidewalks have the air of a hip southern Californian beach town: bustling surf shops, trendy coffee bars and an excellent gourmet "kilo restaurant" called Um Rosa, where regulars pile up huge portions of fresh fish, mussels, salads and organic meats from a buffet bar for 22 Brazilian reais a kilo (NT$336).

It is the beaches beyond Lagoa that are the real attraction, though, and it was time to test them out. Those in the north, Jurere and Ingleses, are the most commercial: a kind of Brazilian Costa del Sol, with high-rise condo developments and tacky restaurants with menus in Spanish to help out all the Argentines. Far better are the beaches to the east and south, facing open ocean: Campeche, Joaquina, Praia Mole and Barra da Lagoa.

On the advice of my Brazilian friend in London we had avoided staying in the city itself and instead based ourselves at Pousada Natur, a privately-run guesthouse in the serene suburb of Campeche -- and a mere block from the beach. An unspoilt boomerang curve of pure white sand, Campeche looks out on a small emerald island that has been declared a national marine park. It has a famous right-break wave that only the legendary surf paradise of Jeffrey's Bay in South Africa can rival. Not that I know what a right break means, but every morning hundreds of daredevil kite surfers and boarders paid tribute to it, doing heart-stopping leaps and breakneck speed twists over the towering barrels.

Surfing is a religion in Floripa and there are several beaches on which to convert. I spent my second afternoon on Barra da Lagoa, under the expert tutelage of Evandro dos Santos, a former Brazilian champion with his own surf school. He had the looks of a film star and the English of a four-year-old. "Watch wavey! Look beachy! Stand uppy!" he advised, before bursting out laughing every time a bathtub-sized tiddler toppled me. That said, my board was as big as a raft and soon enough even I got the hang of things. By the end I was waving like a superstar at the sunbathers on the beach as I rode the ripples in.

Real waves are best left to the pros, though, and luckily my visit coincided with a round of the World Surfing Championship on Praia Mole and Joaquina, two of the best surf beaches in Brazil.

Among the contestant were local stars Fabio Gouveia and Diego Rosa, and six-time world champion (and former Baywatch actor) Kelly Slater.

They were impressive enough, but it was hard to concentrate: on the beach, in front of the cafes spinning break beats and selling beers, was a constant parade of barefoot, thong-wearing beauties: such facsimiles of Gisele Bundchen that for a moment I thought I had spotted her.

Bundchen comes from the neighboring state of Rio Grande do Sul, but since she was unleashed on the world Santa Catarina has been gripped by model mania. As with Rio Grande do Sul, and unlike the rest of Brazil, the interior was settled by German and Polish farmers in the early 19th century. Over the generations their DNA has mixed with Portuguese and Brazilian blood to produce that distinctive dusky, dark blonde look. There are now five international model agencies in Floripa alone.

The hippest hangout of all remains the Confraria das Artes back in Lagoa, opened in 2002 by textile designer Rico Grunfeld, another Sao Paulo transplant. "When I first came here, there was nothing except kitschy discos," he says. "I knew from visiting Paris, London and Miami that what this town needed was a lounge!" So, with somewhat bemusing logic, he created a sprawling nightclub with its own clothing boutique and four indoor-outdoor spaces decorated with vintage furniture, clocks, antique cameras and oil paintings - -- all of which are for sale along with the cocktails.

It seems to have worked: the Confraria is frequently rated by Sao Paulo style mags as one of the best clubs in the country and by 9pm the queue outside stretched to the end of the block.

Seedy or soulless?

The city of Florianopolis dates back to 1752, and the arrival of Portuguese from the island of Madeira. For centuries it was a famous southern port, fortress and whaling post, but after a recent reclamation of the docks to build a highway, it has lost much of its charm. Today it's a maze of modern glass high-rises and faded cement tower blocks facing the mainland. Indeed, I was relieved to be staying out in Campeche: one could get lost in the city, and apart from a gleaming new Sofitel that is being built on the waterfront, the hotels looked seedy or soulless.

And yet remnants of the city's past still exist. The 1898-built public market, just back from the docks, is permanently packed, its stalls teeming with fresh shrimp, mussels, oysters and grouper the size of tractor wheels. Don't miss Box 32 in the heart of the market, a classy cafe with a dozen tables and bar stools where the post-work crowd come for a lager and Portuguese pastries.

A short drive south is another gem: Armazem Viera, built in 1840, the oldest bar on the island, its wooden floor, creaking balcony and ocean-green walls dating back to the glory days of the port. In keeping with Floripa's new image, though, it has updated its drinks menu and features more than 70 premium cachaca cocktails, as well as a dozen mixed with that old sailor's favorite, absinthe.

But there are only so many nights you can spend on the tiles and I saved my final two days to explore the lesser-known parts of the island.

You need a car to get around and after several days of taking pricey taxis, I contacted Marta Chiesa of Brazil Ecojourneys, the first (and so far only) English-speaking tour company to open on the island. A Brazilian who had spent several years in London, she had an insider's eye for the hidden gems. We headed north first, to the mainland-facing village of Santo Antonio do Lisboa. A mere 10 minutes from Floripa and chichi Lagoa, here was another world. Stone bungalows lined the waterfront, sun-bleached fishing boats bobbed in the bays and women rode donkeys down cobbled streets past 250-year-old churches. It looked exactly like Madeira.

We then drove south, through the least developed part of the island, to the even more beautiful town of Ribeirao da Ilha. Old men played chess and draughts on waterfront benches and seafood restaurants lined the water. The best of them was Ostradamus, a sailor-themed oyster bar opened by former hot dog seller Jaime Jose de Barcelos in what used to be the garage of his house. By some way the best seafood restaurant on the island, it was so good that we stayed well past dinner and in the end forwent a final fling at the Confraria.

At the time I was quite happy about the early night, but now I'm not so sure. When I arrived back in London, my Brazilian friend wanted to know whether I had seen Gisele. Apparently she was all over the Brazilian papers, photographed in Florianopolis with new boyfriend and new World Surfing Champion Kelly Slater. One of the pictures of her is on Praia Mole; another looks as if it might be on one of the vintage couches at the Confraria.

Before the recall election drowned out other news, CNN last month became the latest in a long line of media organs to report on abuses of migrant workers in Taiwan’s fishing fleet. After a brief flare of interest, the news media moved on. The migrant worker issues, however, did not. CNN’s stinging title, “Taiwan is held up as a bastion of liberal values. But migrant workers report abuse, injury and death in its fishing industry,” was widely quoted, including by the Fisheries Agency in its response. It obviously hurt. The Fisheries Agency was not slow to convey a classic government

Not long into Mistress Dispeller, a quietly jaw-dropping new documentary from director Elizabeth Lo, the film’s eponymous character lays out her thesis for ridding marriages of troublesome extra lovers. “When someone becomes a mistress,” she says, “it’s because they feel they don’t deserve complete love. She’s the one who needs our help the most.” Wang Zhenxi, a mistress dispeller based in north-central China’s Henan province, is one of a growing number of self-styled professionals who earn a living by intervening in people’s marriages — to “dispel” them of intruders. “I was looking for a love story set in China,” says Lo,

It was on his honeymoon in Kuala Lumpur, looking out of his hotel window at the silvery points of the world’s tallest twin skyscrapers, that Frank decided it was time to become taller. He had recently confessed to his new wife how much his height had bothered him since he was a teenager. As a man dedicated to self-improvement, Frank wanted to take action. He picked up the phone, called a clinic in Turkey that specializes in leg lengthening surgery — and made a booking. “I had a lot of second thoughts — at the end of the day, someone’s going

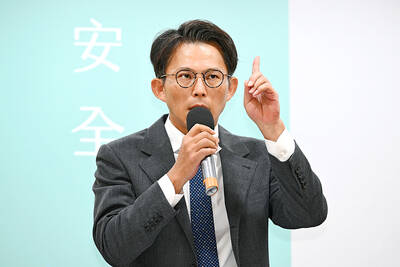

The next few months will be critical in determining the future of the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP). Following party founder Ko Wen-je’s (柯文哲) arrest in September last year, Huang Kuo-chang (黃國昌) effectively became the de facto face of the party and officially became chairman in January. While Ko frequently criticized the ruling Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and insinuated sinister intentions on the part of the DPP’s New Tide faction, his era was largely defined by the TPP slogan “rational, pragmatic, scientific,” albeit defined largely by his definition of what that meant. The tone and language used by the TPP changed dramatically