There are two kinds of families in this village: the relatively rich, who live in tiled villas with air conditioning, and those who still hunt in the wooded hills with bow and arrow and send their sons off to become Buddhist monks when there are too many mouths to feed.

Such distinctions once lay in questions like who tills their paddies by hand under the broad, open skies in this rice-growing region of southwestern China, and who owns a water buffalo to perform the backbreaking work. But more and more these days, relative prosperity is tied to which families have daughters, many of whom go to Thailand and Malaysia to work in brothels.

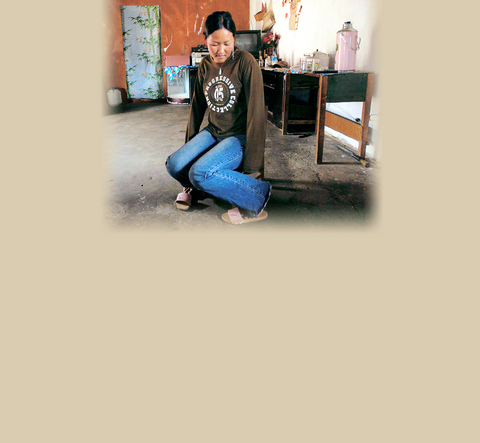

"If you don't go to Thailand and you are a young woman here, what can you do?" said Ye Xiang, 20, whose features still had the pudgy, unformed quality of a teenager's. "You plant and you harvest. But in Thailand and Malaysia, I heard it was pretty easy to earn money, so I went."

PHOTO: NY TIMES

At least 20 other young women from this tiny hamlet, which clings to a hillside just off a trunk road near the Mekong River, have headed off to foreign lands to work in the sex trade. "All of the girls would like to go, but some have to take care of their parents," Ye said.

In this regard, there is nothing peculiar about Langle, at least nothing peculiar for this part of Yunnan province, whose women are favorites in the brothel industry from Thailand, whose national language is related to their own dialect, all the way to Singapore.

Experts say that in some local villages the majority of women in their 20s work in this trade, leaving almost no family untouched, and the young men without mates. Not long ago, many of the recruits were kidnapped to become modern-day sex slaves, but these days the trade has become largely voluntary.

Ye told her story a bit haltingly, but without evident shame. Indeed, her father, a poor farmer, greeted visitors with glasses of hot water, in lieu of tea, and listened, along with a toothless aunt, as she spoke above the tinny noise of a cheap radio in their sparsely furnished one-room shack with a bare cement floor.

She told of her sacrifices -- from hiding in the baggage compartment of a bus to evade immigration police to the groping she endured in bars, where she lived not from a salary, but from patrons' "tips," the sex with strangers and the fear of AIDS. But what underpinned it all were dreams: of marriage to an overseas Chinese, or of at least putting away enough money to be able to return home in triumph.

Ye's first two years in Thailand had not yielded the success she had hoped for. She had earned only enough to eat and buy clothes, not leaving enough to help out her parents. But she was not discouraged, and neither were they. There had been a suitor, and she was eagerly preparing to go back.

"There's a guy in Malaysia, and he calls me every day," she announced proudly, showing off the cellphone he had bought her.

That dreams like these have come true in the past, however naive they may sound, is beyond dispute. This region is strewn with muddy villages crowded with tumbledown shacks, where a gleaming villa with gaudy gold-and-green gates and satellite dish emerges suddenly from the undifferentiated mass.

In some villages, indeed, the migrants' successes have been numerous enough to transform the hamlet itself, sprouting dazzling pockets of affluence that bear comparison with a Shanghai suburb. For this reason, unlike most of China where male children are highly prized, here it is the daughters who literally bring good fortune.

"These girls are motivated by their families and by their neighbors for one basic reason, because they are really poor," said a Beijing-based sociologist who has studied the migrant sex trade in Yunnan.

"The women come home and build big cement homes, and this is like an advertisement to others: This is an easy way to make money. Everyone knows what these women are doing in Thailand, but no one calls it prostitution, even local officials, who talk only of girls `working outside.'"

The sociologist, who asked not to be identified because the subject was so sensitive, said that disease was rampant among women who worked in the sex trade, a situation aggravated by the fact that public health care was denied to illegal foreign workers in Thailand. Despite this, the researcher said, no special efforts have been made to prevent the spread of AIDS in Yunnan by women returning from working in the sex trade in Thailand.

In Mengbin, a small village of the Dai minority, of Thai ethnicity, reached after several hours' drive, the sex trade had completely transformed the local life, starting with the sumptuous villas that had become the rule rather than the exception.

The practice of using beauty and sex to secure a livelihood had even worked its way into the home designs, with tiles depicting willowy, long-haired maidens interspersed here and there on the external walls and gates.

One rich matron, Dao Xiaoshan, proudly invited a visitor into her chateau-like home, with lace-covered couches, four chandeliers, a large, golden Buddhist altar and twin home-entertainment centers.

The secret of this bounty, she said lay in her husband's ownership of a coal mine. Others might conclude her luck was in having two daughters, 23 and 21 and beautiful, as seen in large, formal photographic portraits she had on display, including one showing a daughter dressed up in the gilt and violet regalia of a Thai princess.

"They have been able to work outside, but I've never asked them what they do," said Dao, who appeared to be in her 50s. Lately, she said, one daughter had found happiness with a rich Singaporean, the other with a wealthy Malaysian.

What about the young men here? "Dai boys can't marry Dai girls, because they all leave, and the ones who come back don't like the local boys anymore," Dao said, with a chuckle.

"Dai girls are beautiful, and they are very popular, but not all of them bring home money. Some of them don't know how to do anything but spend money and have a good time."

Taiwan has next to no political engagement in Myanmar, either with the ruling military junta nor the dozens of armed groups who’ve in the last five years taken over around two-thirds of the nation’s territory in a sprawling, patchwork civil war. But early last month, the leader of one relatively minor Burmese revolutionary faction, General Nerdah Bomya, who is also an alleged war criminal, made a low key visit to Taipei, where he met with a member of President William Lai’s (賴清德) staff, a retired Taiwanese military official and several academics. “I feel like Taiwan is a good example of

“M yeolgong jajangmyeon (anti-communism zhajiangmian, 滅共炸醬麵), let’s all shout together — myeolgong!” a chef at a Chinese restaurant in Dongtan, located about 35km south of Seoul, South Korea, calls out before serving a bowl of Korean-style zhajiangmian —black bean noodles. Diners repeat the phrase before tucking in. This political-themed restaurant, named Myeolgong Banjeom (滅共飯館, “anti-communism restaurant”), is operated by a single person and does not take reservations; therefore long queues form regularly outside, and most customers appear sympathetic to its political theme. Photos of conservative public figures hang on the walls, alongside political slogans and poems written in Chinese characters; South

Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (蔣萬安) announced last week a city policy to get businesses to reduce working hours to seven hours per day for employees with children 12 and under at home. The city promised to subsidize 80 percent of the employees’ wage loss. Taipei can do this, since the Celestial Dragon Kingdom (天龍國), as it is sardonically known to the denizens of Taiwan’s less fortunate regions, has an outsize grip on the government budget. Like most subsidies, this will likely have little effect on Taiwan’s catastrophic birth rates, though it may be a relief to the shrinking number of

Institutions signalling a fresh beginning and new spirit often adopt new slogans, symbols and marketing materials, and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) is no exception. Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文), soon after taking office as KMT chair, released a new slogan that plays on the party’s acronym: “Kind Mindfulness Team.” The party recently released a graphic prominently featuring the red, white and blue of the flag with a Chinese slogan “establishing peace, blessings and fortune marching forth” (締造和平,幸福前行). One part of the graphic also features two hands in blue and white grasping olive branches in a stylized shape of Taiwan. Bonus points for