Love, fear and revulsion are some of the feelings movies are particularly adept at conjuring, but grief is much more elusive because it's so private. How do you evoke the inner life of a solitary mourner mutely contemplating the world from behind an emotional shroud?

Love Letter, the feature film debut of the Japanese director Shunji Iwai offers an intriguing narrative platform from which to experience the sadness of its bereft central character, Hiroko Watanabe (Miho Nakayama).

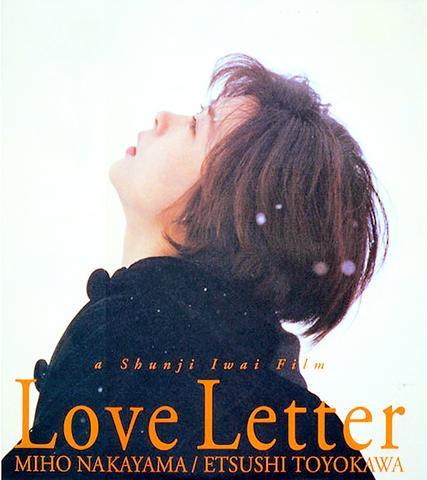

PHOTO COURTESY OF IMAGENET

The film begins at a memorial service two years after the death of her fiance in a mountaineering accident. After the ceremony, Hiroko, who lives in Kobe, discovers her lover's high-school yearbook while sorting through his belongings. Finding what she assumes is his old address in the back, she impulsively writes him a letter and mails it, as though she were sending a note to heaven, without expecting an answer.

In a stunning coincidence the letter is delivered to a young woman, Itsuki Fujii, who not only has the same name as her dead lover but was in his high school class in Otaru, a town in northern Japan. A correspondence that begins tentatively intensifies when Itsuki, at Hiroko's request, begins raking her mind for memories of the classmate with whom she was continually confused because they shared the same name.

As old memories are awakened, the movie flashes back to scenes of the pranks played by classmates on the two Itsukis, who developed a secret bond even while professing to resent each other for having the same name and being tormented for it. When they worked side by side in the school library, the male Itsuki (Takashi Kashiwabara) played a hide-and-seek game involving library cards and hidden books that a younger generation of students working in the same library has discovered and elevated into a kind of school myth.

Adding metaphorical richness to the movie, which at moments recalls Krzysztof Kieslowski's Double Life of Veronique, is the fact that Nakayama plays both Hiroko and the grown-up Itsuki, who turn out to have a twinlike physical resemblance, although their personalities are very

different.

Itsuki, moreover, has also suffered a loss. Not long ago, her father died of pneumonia on the way to the hospital. And Itsuki, who when first glimpsed is suffering from a bad cold, has nightmares that she too will be suddenly stricken. Eventually Hiroko and her fiance's best friend, Akiba (Etsushi Toyokawa), who is in love with her and wants to marry her, travel to Otaru. Akiba hopes that Hiroko, by meeting her correspondent, can shake off the ghosts of the past and begin loving him.

Love Letter swirls with unsettling notions of multiple identity, memory and parallel lives. But they never quite mesh into a fully realized concept of the characters' lives and how they intersect. With a running time of nearly two hours, the film sometimes meanders so fitfully that it loses its narrative drive.

Nor does it find visual images compelling enough to give its scenario a metaphorical underlining. For those you would have to turn to another Japanese film, Hirokazu Kore-eda's 1996 work, Maborosi. In that extraordinarily atmospheric and emotionally wrenching movie, every particle of light and air is charged with sadness.

One of the biggest sore spots in Taiwan’s historical friendship with the US came in 1979 when US president Jimmy Carter broke off formal diplomatic relations with Taiwan’s Republic of China (ROC) government so that the US could establish relations with the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Taiwan’s derecognition came purely at China’s insistence, and the US took the deal. Retired American diplomat John Tkacik, who for almost decade surrounding that schism, from 1974 to 1982, worked in embassies in Taipei and Beijing and at the Taiwan Desk in Washington DC, recently argued in the Taipei Times that “President Carter’s derecognition

This year will go down in the history books. Taiwan faces enormous turmoil and uncertainty in the coming months. Which political parties are in a good position to handle big changes? All of the main parties are beset with challenges. Taking stock, this column examined the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) (“Huang Kuo-chang’s choking the life out of the TPP,” May 28, page 12), the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) (“Challenges amid choppy waters for the DPP,” June 14, page 12) and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) (“KMT struggles to seize opportunities as ‘interesting times’ loom,” June 20, page 11). Times like these can

June 23 to June 29 After capturing the walled city of Hsinchu on June 22, 1895, the Japanese hoped to quickly push south and seize control of Taiwan’s entire west coast — but their advance was stalled for more than a month. Not only did local Hakka fighters continue to cause them headaches, resistance forces even attempted to retake the city three times. “We had planned to occupy Anping (Tainan) and Takao (Kaohsiung) as soon as possible, but ever since we took Hsinchu, nearby bandits proclaiming to be ‘righteous people’ (義民) have been destroying train tracks and electrical cables, and gathering in villages

Dr. Y. Tony Yang, Associate Dean of Health Policy and Population Science at George Washington University, argued last week in a piece for the Taipei Times about former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) leading a student delegation to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) that, “The real question is not whether Ma’s visit helps or hurts Taiwan — it is why Taiwan lacks a sophisticated, multi-track approach to one of the most complex geopolitical relationships in the world” (“Ma’s Visit, DPP’s Blind Spot,” June 18, page 8). Yang contends that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has a blind spot: “By treating any