Bobby Darnell, a 34-year-old Texan who has lived in New York since 1996, does not fit the stereotype of a club drug user. For six years, he was an administrator for nonprofit groups, and he has sung in the New York City Gay Men's Chorus since 1998. "The chorus is mostly people from small towns, not club kids or fashion people," Darnell said. "That's sort of what attracted me to it."

But four years ago he began casually exploring the club scene and tried crystal meth, the street version of the powerful stimulant methamphetamine, for the first time. After he lost a job to cutbacks in 2001 and found himself at home with nothing to do but look for work, he began to spend long hours on the Internet, and fell into a pattern of casual sexual encounters that sometimes included crystal meth, which intensifies sexual drive and lowers inhibitions.

PHOTOS: NY TIMES

"I never did it for days and days at a time, just for a couple of days every two or three weeks," Darnell said. It took a long time for him to recognize that he had a problem. But by then, he had driven away all his old friends. "I would cancel things, and then people just stopped calling after a while. Everyone in New York is so busy, it's very easy for someone to disappear."

Eventually Darnell was hospitalized. Only his connection with members of the chorus pulled him back from the brink. "There was one older gentleman," he said, "who would just come and hold my hand all day during those first couple of weeks" as he drifted in and out of consciousness.

Stories like Darnell's have become increasingly common as crystal meth has spread beyond New York's gay club culture to a wider cross section of gay men, especially young ones. The drug, which can be sniffed as a powder, smoked in crystalline shards or dissolved in water and injected, is considered just as addictive as crack cocaine. It is blamed for a host of problems, ruining its users' health, robbing them of their jobs and sometimes driving them to mental illness, suicide or death by overdose. But its effects go well beyond the wreckage of individual lives, creating a ripple effect in the larger social world of gay men in the city. Long used by blue-collar Americans as an endurance enhancer and a recreational drug, crystal meth first became popular in gay dance clubs in New York in the mid- to late 1990s, having migrated east from the gay scenes in Los Angeles, San Francisco and Honolulu. But in the last three or four years, its use here has grown enormously.

Darnell, who has pulled his life together and is now working as a receptionist, said four or five other chorus members had started experimenting with the drug around the same time he did. "One by one these people wouldn't be dancing anymore, one by one they would lose their jobs, one by one they wouldn't be at rehearsal anymore," he said.

Many men say they have lost friendships or romantic relationships to crystal meth, and many who don't use it keep their distance adamantly from those who do. The rift is apparent on Web sites and in chat rooms where men advertise for romantic or sex partners, often using coded references like "PNP" (for "party and play," meaning drugs with sex) or "No PNP," "chem friendly" or "absolutely no tweakers" (a reference to people strung out on the drug).

Crystal meth "turns people into anti-social zombies," said Trip Zanetis, 23, a nightclub publicist who said he hates what it is doing to his social world. "It makes people hostile and delusional. The vibe is much more negative and colder than in the past, thanks to this drug."

As Max Wixom, 26, a theatrical publicist and production designer, put it, "Even the way gay men look at each other is different."

"In 1996, when I first arrived in New York and started going out, you could easily get to know people," Wixom said. "It felt like a community or a brotherhood." But with the rise of crystal meth, he said, gay night life has turned "more predatory and dehumanized."

Dr. Steven Lee, a New York psychiatrist who specializes in treating crystal meth addicts, said there is now "a much harder edge in New York gay clubs than in the past." This change, he said, is largely because of the drug: in addition to its sexual and stimulant effects, crystal meth promotes aggression.

"Some of my patients talk about how they feel on crystal meth as akin to being robots programmed with the sole purpose of doing more crystal and having more sex," Lee said. The drug also causes paranoia in regular users and can eventually lead to psychotic episodes.

Gay Men's Health Crisis, founded in the 1980s to help people with AIDS, said that two years ago, it received very few hot line calls related to crystal meth, but that it now gets about five a day. Fewer than half the new clients in its drug counseling program reported crystal meth use as their main drug problem three years ago. This year the figure is 80 percent.

Crystal Meth Anonymous, a support and recovery group, began operating in New York five years ago with one meeting a week, which was never attended by more than six people, said Raul M, one of the group's early members. Now there are 23 meetings, some attracting crowds of more than 100. "In the last year we've almost doubled in membership," he said. "We expect to add new meetings later this year, but we're running out of venues."

A study last year by researchers at Hunter College found that about 20 percent of gay men in New York had tried crystal meth and that about half that number had used it in the three months preceding the study.

John Lee, 24, a graduate of Dartmouth and a research analyst at a hedge fund company, said the drug is causing strange behavior in his own social circle. Although he said he never uses crystal meth and only occasionally goes out clubbing, several friends -- college-educated and middle class -- go dancing and use it almost every weekend.

"They're constantly irritated and it affects the way they relate to other people, but they don't realize it," Lee said. One Filipino friend frequently gets into fights with people he imagines are making fun of his accent. "He'll scream at them and start shoving them," Lee said. "He thinks it's racism, but it's strictly his paranoia."

It is in New York's gay club world -- where, according to a recent study by the Center for HIV/AIDS Educational Studies and Training in New York, 62 percent of those who use any club drugs reported "significant and frequent use" of crystal meth -- that the social effects have been most strongly felt. Aficionados of the scene say dance clubs have become sterile environments filled with monotonous music and detached dancers.

"I've been in this business for 25 years, and I've seen four or five different sets of people come and go," said John Blair, a longtime party promoter who owns the Chelsea bar XL and is a co-owner of Avalon (the former Limelight), where he gives regular Sunday night parties.

"Each group of people goes through a similar experience with different music and different drugs," Blair said. "But crystal is by far the worst drug I've ever seen happen to night life. It not only takes over people's lives, but it really negates what the whole scene is supposed to be about."

In fact, the rise in crystal meth use has hurt the club industry in New York, particularly the big-box clubs famous for after-hours dance marathons -- some gay, some mixed -- that start at 2am or 3am and often continue until 7pm or 8pm the following evening. Drug crackdowns by the police on the clubs Sound Factory in March and Exit last year were at least partly due to such parties.

And as people become heavier users, they are moving away from the club scene, becoming increasingly reclusive and focused on Internet sex liaisons -- and, in some cases, on just maintaining their drug habits. Darnell, the Gay Men's Chorus member, said that after he lost his job in 2001, he barely left his apartment, which became a nightmarish mess. A neighbor of his in Hell's Kitchen, who was also using crystal meth and had also become a shut-in, allowed his electricity to be shut off and his cats to bear litter after litter.

Dan Carlson, a founder of an anti-crystal-meth organization called the HIV Forum NYC, said one club promoter recently offered to help with the group's work. "I said, `Great, but what's in it for you?"' Carlson said. "And he's, like, `This Internet stuff is killing my business."'

Carlson is one of a small but growing number of vocal crystal-meth opponents, many of them former users themselves. He started the HIV Forum NYC last July with Dr. .Bruce Kellerhouse, a psychologist, after they became angry at the news that HIV infections had jumped 18 percent nationwide among gay and bisexual men since 1999 -- an increase that he and others involved in HIV prevention blame largely on crystal meth, which has been associated with high rates of unprotected sex. (As yet, there is no firm scientific data showing conclusively that crystal meth is behind the rise, but anecdotal evidence from doctors in New York suggests that the drug plays a role in anywhere from 50 percent to 75 percent of new HIV cases in the city.)

"For many years," Carlson said, "crystal has built this reputation as being glamorous, being fun. Anyone who's edgy is doing crystal meth. And if you're not, you're not cool -- you're not part of the `in' crowd, not part of the scene."

Last month, the HIV Forum NYC held a public meeting at the Fashion Institute of Technology that drew 300 people -- doctors, drag queens, city officials, clubbers, law enforcement officers, recovering addicts -- and was led by John Cameron Mitchell, the director, writer and star of the film Hedwig and the Angry Inch. The discussion featured personal testimony from audience members and panelists about the negative impact that crystal meth has had on the gay world.

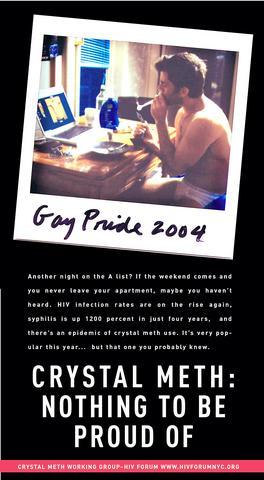

The HIV Forum also started an advertising campaign in June, to coincide with the annual Gay Pride celebration. The latest ads, displayed on phone booths in Chelsea, feature a buff young man clad only in briefs, looking at a computer screen and sucking on a glass crystal-meth pipe filled with smoke. The caption begins, "Another night on the A List?" and the tagline says, "Crystal meth: Nothing to be proud of."

The ad campaign appeared a few months after a veteran AIDS activist and HIV Forum member named Peter Staley spent US$6,000 of his own money to put up posters on phone booths in Chelsea saying: "Huge Sale! Buy crystal, get HIV free!"

But not everyone approves of such measures. In the May issue of the gay magazine Genre, a writer who calls himself Diabolique criticized people like Staley as "nanny nelly liberal activists" and accused them of helping spur a continuing police crackdown on gay night life.

"It combines the worst aspects of over-the-top anti-drug hysteria with the best of `get press at any cost' '80s-era AIDS activism," Diabolique wrote. "The ads don't work on drug-taking hedonists, they work on riling up the news media, public health and law enforcement officials."

"There's a total split in the gay community about this issue," Diabolique said in an interview. "Most gay men I know thought the `Buy crystal, get HIV' ads were ridiculous."

"Crystal meth is a problem," he said. "It's the worst drug problem I've seen in all my years of clubbing. But hysterical anti-drug, anti-sex propaganda does nothing to solve that problem."

The editor in chief of Genre, Bill Henning, said he regards the things that organizations like HIV Forum say as mainly puritanical propaganda. "It's great they're bringing attention to it, but they're not reaching the people they need to reach with all this finger-wagging," he said. "It's the same sort of anti-sex, anti-drug argument that's been going on in the gay community for years."

But Blair, the party promoter, said the message may be getting through. The closings of most after-hours parties, the advertising campaigns and the personal horror stories about the drug are beginning to have an effect, he said.

"Thank god for GMHC and the HIV Forum," he said. "In the last year, things have started to turn around. Using crystal is not something you brag about anymore. There's a growing stigma against it, especially among the younger set. As people get more and more information, they realize the harm it's doing, not just to users but to the community as a whole."

This year will go down in the history books. Taiwan faces enormous turmoil and uncertainty in the coming months. Which political parties are in a good position to handle big changes? All of the main parties are beset with challenges. Taking stock, this column examined the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) (“Huang Kuo-chang’s choking the life out of the TPP,” May 28, page 12), the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) (“Challenges amid choppy waters for the DPP,” June 14, page 12) and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) (“KMT struggles to seize opportunities as ‘interesting times’ loom,” June 20, page 11). Times like these can

June 23 to June 29 After capturing the walled city of Hsinchu on June 22, 1895, the Japanese hoped to quickly push south and seize control of Taiwan’s entire west coast — but their advance was stalled for more than a month. Not only did local Hakka fighters continue to cause them headaches, resistance forces even attempted to retake the city three times. “We had planned to occupy Anping (Tainan) and Takao (Kaohsiung) as soon as possible, but ever since we took Hsinchu, nearby bandits proclaiming to be ‘righteous people’ (義民) have been destroying train tracks and electrical cables, and gathering in villages

Dr. Y. Tony Yang, Associate Dean of Health Policy and Population Science at George Washington University, argued last week in a piece for the Taipei Times about former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) leading a student delegation to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) that, “The real question is not whether Ma’s visit helps or hurts Taiwan — it is why Taiwan lacks a sophisticated, multi-track approach to one of the most complex geopolitical relationships in the world” (“Ma’s Visit, DPP’s Blind Spot,” June 18, page 8). Yang contends that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has a blind spot: “By treating any

Swooping low over the banks of a Nile River tributary, an aid flight run by retired American military officers released a stream of food-stuffed sacks over a town emptied by fighting in South Sudan, a country wracked by conflict. Last week’s air drop was the latest in a controversial development — private contracting firms led by former US intelligence officers and military veterans delivering aid to some of the world’s deadliest conflict zones, in operations organized with governments that are combatants in the conflicts. The moves are roiling the global aid community, which warns of a more militarized, politicized and profit-seeking trend