In The Station Agent a man named Fin settles into a remote outpost -- a rundown train depot in the wilds of New Jersey -- that is so restful it seems perfect for him. The movie's writer and director, Tom McCarthy, has such an appreciation for quiet that it occupies the same space as a character in this film, a delicate, thoughtful and often hilarious take on loneliness.

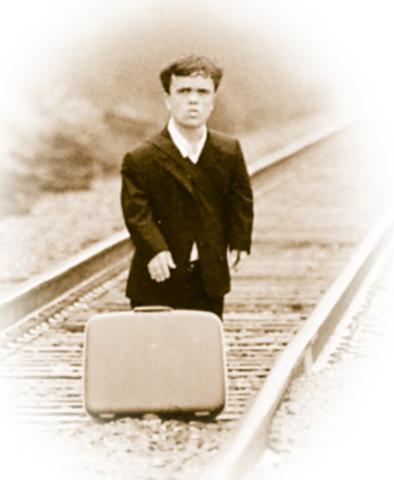

The Station Agent played at the Sundance Film Festival last year, and it's a relief to see it finally released; it's the kind of appetizing movie you want to share with others. Fin (Peter Dinklage), with his low, rational voice and intense stare, has moved into the remote spot after inheriting the depot, a dingy yet lovely shack out of a Walker Evans photograph, from Henry (Paul Benjamin), his mentor and the owner of the model-train store where Fin works in mournful silence.

Fin is 1.32m -- he has no problem referring to himself as a dwarf -- but Henry, with his sour expression and slack shoulders, seems even smaller, though he's of average height. The unperturbed air seems to take something out of him: he could be waiting to die.

McCarthy treats Fin's new life as if his protagonist were emerging from underwater and had to adjust to the onrush of aural assault. Much of this comes from Joe (Bobby Cannavale), the relentlessly friendly and talky Cuban who pulls up every day in his food truck to run what must be the loneliest retail location not staffed by the Maytag repairman. Hawking coffee and fanning up a cloud of busy, pushy and likable chatter, Joe elbows his way into the taciturn Fin's life.

Fin's obsession is trains, which he doesn't really want to talk about. He'd rather work with them, and with the depot he's been left what is essentially the world's largest model-train set. The station, though, is mostly deserted, and it provides an incomplete fantasy. For Fin the dream always seems half-empty at best.

The director plays up the amusing contrasts between the serene, diminutive Fin, whose dignity seems unassailable until he's finally ruffled, and the big, buffed Joe, whose unremitting volubility is cotton-candy charm. He's a puppy who can't help trailing after someone he adores and he uses words to mark his territory; the pair's relationship is goofily enchanting.

Joe is aggressive simply because he takes up so much space, and The Station Agent, which opens today in New York and Los Angeles, allows Cannavale to give his finest performance. There are depths of neediness and happiness coexisting in him and he doesn't bother to separate the warring factions in this charismatic supporting turn.

Dinklage's generosity should also be noted; he can be a forceful actor. He proved his worth in Tom DiCillo's making-of-an-indie-film-disaster comedy, Living in Oblivion. In that film he portrayed a cliched dwarf in an imagined dream sequence and verbally burned a layer of skin and nerve endings off the movie-within-a-movie's director (Steve Buscemi), flaying him for his lack of

imagination.

A movie about a dwarf certainly flirts with being cringe-worthy, at least in the abstract, but McCarthy deals with his creations as characters. What's most important about Fin is the detachment he imposes on himself, his resignation to loneliness. But his vulnerability becomes evident during a drunken rage in a tavern, when he shows why he keeps himself emotionally locked away. After being subjected to insults, he biliously shouts to gawkers in the bar, "Take a good look."

Joe's alone, too, and clings to the silent, brooding Fin as if he were a refrigerator magnet. When the grieving artist Olivia (Patricia Clarkson) literally barrels into the picture -- she nearly runs over Fin with her car -- The Station Agent takes on a deeper, more tantalizing shape. Clarkson has been delivering meaty, juicy plums to movies for several years; she's become the Barry Bonds of low-budget film.

Olivia is flushed with pain, and embarrassed by it. The power in Clarkson's performance comes from Olivia's recognizing parts of herself that she's been suppressing.

These three loners slowly melt into one another, but the relationship doesn't come easily to any of them. Their unspoken anguish says plenty, as does Fin's ability to provoke conversation from those who insert themselves into his circle. He clearly doesn't seek them out, except one. He does show some tenderness to a young visitor to his depot, a little girl, Cleo, played with unapologetic curiosity by Raven Goodwin. She's the one person Fin will deal with directly, and his patience tickles her; it compels her to spray him with questions.

This exception aside, McCarthy proves himself so crafty at making the unvoiced sentiments the heart of the film that the movie becomes shocking in moments when Fin vents his fury. If he weren't allowed the opportunity, however, you'd worry that The Station Agent might implode, folding in on itself in pent-up emotion.

McCarthy does allow the movie bigger scenes, providing a burst of contentment for the withdrawn Fin. In one, Joe drives next to a train, while Fin, a quiet smile on his face, catches the locomotive with his video camera. After that, it's a return to the depot, which is such a welcoming, ramshackle oasis that you think the producers might offer it on eBay one day. I'd buy it.

US President Donald Trump may have hoped for an impromptu talk with his old friend Kim Jong-un during a recent trip to Asia, but analysts say the increasingly emboldened North Korean despot had few good reasons to join the photo-op. Trump sent repeated overtures to Kim during his barnstorming tour of Asia, saying he was “100 percent” open to a meeting and even bucking decades of US policy by conceding that North Korea was “sort of a nuclear power.” But Pyongyang kept mum on the invitation, instead firing off missiles and sending its foreign minister to Russia and Belarus, with whom it

When Taiwan was battered by storms this summer, the only crumb of comfort I could take was knowing that some advice I’d drafted several weeks earlier had been correct. Regarding the Southern Cross-Island Highway (南橫公路), a spectacular high-elevation route connecting Taiwan’s southwest with the country’s southeast, I’d written: “The precarious existence of this road cannot be overstated; those hoping to drive or ride all the way across should have a backup plan.” As this article was going to press, the middle section of the highway, between Meishankou (梅山口) in Kaohsiung and Siangyang (向陽) in Taitung County, was still closed to outsiders

Many people noticed the flood of pro-China propaganda across a number of venues in recent weeks that looks like a coordinated assault on US Taiwan policy. It does look like an effort intended to influence the US before the meeting between US President Donald Trump and Chinese dictator Xi Jinping (習近平) over the weekend. Jennifer Kavanagh’s piece in the New York Times in September appears to be the opening strike of the current campaign. She followed up last week in the Lowy Interpreter, blaming the US for causing the PRC to escalate in the Philippines and Taiwan, saying that as

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has a dystopian, radical and dangerous conception of itself. Few are aware of this very fundamental difference between how they view power and how the rest of the world does. Even those of us who have lived in China sometimes fall back into the trap of viewing it through the lens of the power relationships common throughout the rest of the world, instead of understanding the CCP as it conceives of itself. Broadly speaking, the concepts of the people, race, culture, civilization, nation, government and religion are separate, though often overlapping and intertwined. A government