Goya y Lucientes (1746 to 1828) is one of those towering figures whose vision and achievements still loudly echo down the centuries -- a colossus like Shakespeare or Dickens, at once emblematic of his place and times and thoroughly modern. Just as Goya's etchings known as Los Desastres de la Guerra convey for the first time the full, blood-soaked awfulness of combat, so do the phantasmagorical images of his iconic Black Paintings -- an abandoned dog peering into the abyss, a demented Saturn devouring one of his own children, a pair of embattled men locked in a primordial feud -- look forward to the existential terrors of our own age.

Robert Hughes' dazzling new study of Goya not only conveys the range and prescience of the artist's work with enormous acuity and verve, but also conjures the world of 18th- and early 19th-century Spain with vivid, pictorial ardor.

Writing in fierce, tactile prose, Hughes jolts the reader into a visceral appreciation of Goya's art, while at the same time situating Goya's work against the historical backdrop of Spain's harrowing war with Napoleon and the country's sufferings under a series of ineffectual and backward rulers.

Hughes deconstructs Goya's masterly technique, from his use of light and shadow to his framing of often chaotic subject matter with strict, geometrical compositions. And, most important, he communicates the moral urgency of Goya's art and its remarkable eloquence and scope: its determination to bear witness to the great historical subjects of the day while tackling the full spectrum of folly and joy and torment that is the human condition, an audacious ambition sadly lacking in so much of contemporary art.

There were many different Goyas, of course: Goya the court painter, the dutiful servant of kings; Goya the master portrait painter, a meticulous observer of fashion and gesture and class; Goya the satirist and scourge, assailing war and injustice and the sins of the Inquisition; and Goya the haunted pessimist, chronicler of insanity, madness and violent death.

Hughes explicates the relationship between these many Goyas, showing how the painter developed over the years, even as he debunks the many myths that have sprung up around the artist's life. Hughes reminds us that for all of his anticlerical fervor, Goya remained a Roman Catholic, and he argues that the painter was not mad, as popularly believed, only fascinated, like many under the spell of Romanticism, with madness as an extreme mental state and a part of the human condition.

Near the beginning of this volume, Hughes observes that Goya was both "one of the few great describers of physical pain, outrage, insult to the body" and "a mighty celebrant of pleasure."

"He loved everything that was sensuous: the smell of an orange or a girl's armpit; the whiff of tobacco and the aftertaste of wine; the twanging rhythms of a street dance," he writes. In retrospect, Goya is perhaps best described as a realist endowed with a tragic sense of life, an artist whose creed, in Terence's words, was "I think nothing human alien to me."

While images of pleasure pervade Goya's earlier work -- glimpses of men and women picnicking on the banks of a river, children frolicking in a garden, nubile women gazing flirtatiously at the viewer -- darker, more disturbing images came to predominate in the wake of a serious illness that left the painter functionally deaf after 1793. The deafness, as Hughes notes, meant isolation and immurement within "the silent prison of the self." It left Goya with the fear that he would no longer be "able to impose himself upon the world," heightened his sense of mortality and focused his imagination on "disaster and mayhem."

In fact, as Goya's work grew more inward and expressionistic, it became freighted with nightmare visions: a picador being horribly gored and tossed by a furious bull; shipwreck survivors gasping for life in a roiling sea; murderous bandits threatening a group of terrified travelers; madmen crudely gesticulating in a prisonlike asylum; women being raped and murdered in a cavernous void.

Witches -- emblems of the superstitions many in Enlightenment-era Spain still clung to -- proliferate in Los Caprichos, and his oeuvre serves up other bizarre, enigmatic images as well: a huge, muscular giant rising over the Spanish landscape, like a god of war; a cadaver holding a piece of paper emblazoned with the single word "Nada" ("Nothing"); a quartet of hideous creatures -- perhaps the three Fates or Daughters of the Night, with a victim -- hovering over a chilly river landscape.

Many of the most alarming images belong to the Black Paintings, which covered the walls of Goya's farmhouse outside Madrid. They are images that reflect the despair Goya and other liberals felt after King Fernando VII was restored to the Spanish throne, and all that that event inevitably meant: "A weak but still absolute tyranny, the Church in the saddle, the Inquisition back, the Constitution erased."

Although a professor of art history has recently questioned Goya's authorship of those paintings, Hughes clearly has no patience for such theories, arguing that the works are "not only among the most dramatic painted images Goya ever made," but also his "most private by far": "He had no audience in mind. He was talking to himself."

Those paintings, like Los Caprichos and Los Desastres, attest to both Goya's radical modernity and his enduring mythic power -- his identity, as Hughes puts it in this galvanic volume, as "a true hinge figure, the last of what was going and the first of what was to come."

Taiwan can often feel woefully behind on global trends, from fashion to food, and influences can sometimes feel like the last on the metaphorical bandwagon. In the West, suddenly every burger is being smashed and honey has become “hot” and we’re all drinking orange wine. But it took a good while for a smash burger in Taipei to come across my radar. For the uninitiated, a smash burger is, well, a normal burger patty but smashed flat. Originally, I didn’t understand. Surely the best part of a burger is the thick patty with all the juiciness of the beef, the

The ultimate goal of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is the total and overwhelming domination of everything within the sphere of what it considers China and deems as theirs. All decision-making by the CCP must be understood through that lens. Any decision made is to entrench — or ideally expand that power. They are fiercely hostile to anything that weakens or compromises their control of “China.” By design, they will stop at nothing to ensure that there is no distinction between the CCP and the Chinese nation, people, culture, civilization, religion, economy, property, military or government — they are all subsidiary

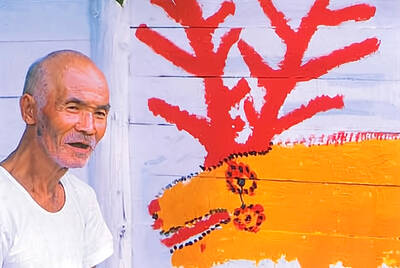

Nov.10 to Nov.16 As he moved a large stone that had fallen from a truck near his field, 65-year-old Lin Yuan (林淵) felt a sudden urge. He fetched his tools and began to carve. The recently retired farmer had been feeling restless after a lifetime of hard labor in Yuchi Township (魚池), Nantou County. His first piece, Stone Fairy Maiden (石仙姑), completed in 1977, was reportedly a representation of his late wife. This version of how Lin began his late-life art career is recorded in Nantou County historian Teng Hsiang-yang’s (鄧相揚) 2009 biography of him. His expressive work eventually caught the attention

This year’s Miss Universe in Thailand has been marred by ugly drama, with allegations of an insult to a beauty queen’s intellect, a walkout by pageant contestants and a tearful tantrum by the host. More than 120 women from across the world have gathered in Thailand, vying to be crowned Miss Universe in a contest considered one of the “big four” of global beauty pageants. But the runup has been dominated by the off-stage antics of the coiffed contestants and their Thai hosts, escalating into a feminist firestorm drawing the attention of Mexico’s president. On Tuesday, Mexican delegate Fatima Bosch staged a