Lashed to Rod Palm's dock at his Strawberry Island home may be the key to unraveling one of the most enduring mysteries of North American maritime history.

Or it might just be an old anchor.

To Palm and some others in this small community on the lush west coast of Vancouver Island, the anchor fulfills decades of dreams. They say they are convinced that it once belonged to the Tonquin, a fur-trading vessel that established the first American settlement on the West Coast before being lost off Vancouver Island in 1811. If true, it would be a momentous discovery.

PHOTO: NY TIMES

Despite several searches dating to 1890, the wreck of the Tonquin has never been found. But many doubt that the 2.6m-by-2.5m anchor sitting on Palm's dock changes anything.

E.W. Giesecke, a retired professor and Tonquin scholar in Olympia, Washington, said there were four sites where the wreck of the Tonquin might be, Clayoquot Sound near Tofino being just one of them.

"It's conjecture," Giesecke said.

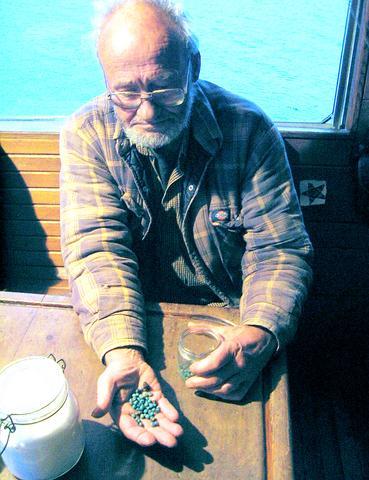

At 61, Palm is one of the older working divers on Vancouver Island. The deck around his house, an old ferry in a concrete dry dock, is littered with the detritus of 30 years of salvage work: whale skulls, anchors, crab baskets.

But it is the island's many shipwrecks, particularly the Tonquin, that captivate Palm. So in April when a crab fisherman asked Palm to investigate a snag that had fouled his traps in Templar Strait, he was excited to discover that the protuberance was the exposed arm of a large anchor.

He later returned to retrieve the anchor, and now it sits in his ferry house on Strawberry Island.

From Strawberry Island, which he owns, Palm said he had watched Tofino transform from a salmon fishing village to a tourist destination, and his hope is that his discovery could be a boon for the town's fading maritime legacy.

"It's totally turned into a tourism-dependent village," Palm said. "It's not the sleepy village it used to be."

But his claim that the anchor is from the Tonquin has set off a lively debate among maritime historians and underwater archaeologists, and his determination to keep the anchor in Tofino has perturbed the provincial government.

"We don't know what Rod found, or even if it's necessarily connected to a ship. What we know is he found an anchor," said Jacques Marc, president of the Underwater Archaeological Society of British Columbia.

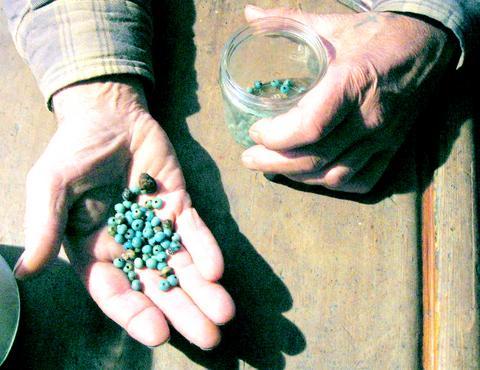

What is known is that the anchor is of a design used by fur-trading ships of the Tonquin's era, and that along with the anchor Palm found blue beads of the type used in the trade, Marc said.

Beyond that, he said, any statement that the mystery of the Tonquin has been solved is premature.

The Tonquin, a 30m vessel built in the East River, New York, shipyard of Adam and Noah Brown, was launched by John Jacob Astor as part of his grand commercial scheme to loosen the grip that the British and Russians had on the Pacific fur trade. In the process Astor established the first permanent American colony in the far West, Astoria.

The Tonquin's voyage -- most famously documented by Washington Irving's 1836 book Astoria -- occurred at a time when the Pacific Northwest might as well have been the moon. While the coast was well traveled by trading ships, it was only six years after Lewis and Clark first reached the Pacific, and the interior remained a dark mystery.

The legacy of Astor and the Tonquin survives today as the town of Astoria, Oregon, at the mouth of the Columbia River. But the ship and much of its crew met with a bloody end.

As told by Irving, while trading for furs somewhere on the coast of Vancouver Island, the Tonquin's captain, a prickly New Yorker named Jonathan Thorn, slapped a local chief with a sea otter pelt.

Outraged, scores of Indians mounted an assault on the ship the next day, massacring most of the crew. Nevertheless, one man, a clerk, survived long enough to set fire to an estimated 4.5 tons of gunpowder in the Tonquin's hold.

Irving described the destruction, relayed by an Indian translator who survived the incident:

"The ship had disappeared, but the bay was covered with fragments of the wreck, with shattered canoes, and Indians swimming for their lives, or struggling with the agonies of death."

Since the 1950s, hundreds of thousands of dollars have been spent on efforts to find the lost ship.

On a recent evening, a small group gathered in Palm's kitchen to discuss his discovery and the formation of a Tonquin Foundation.

Joining Palm were David Griffiths, a documentary filmmaker and diver, and Joseph Martin, a member of the Tla-o-qui-aht First Nations, whose traditional territory rings Clayoquot Sound.

The goal of the foundation, Griffiths said, would be to "leapfrog all of that heavy meanderings at the different levels of government" that could bog down any archaeological work. He said the foundation planned to work closely with the local Tla-o-qui-aht tribe, whose members have an oral history describing their part in the Tonquin disaster, to raise enough money to finance a survey of the strait to determine if a wreck was present.

Until then, he said, Palm would hold on to the anchor, possibly using it as the centerpiece of a future maritime heritage center in Tofino.

The provincial government is likely to object.

Steven Acheson, an archaeologist with British Columbia's Archaeology and Registry Services Branch in Victoria, said a provincial law, the Heritage Conservation Act, gave the government of British Columbia ultimate authority over any artifacts discovered in the province.

He saidthat, according to the law, the anchor should be turned over to a research institution for analysis.

Palm said he would oppose any efforts to remove the anchor from the Strawberry Island site.

"I don't think they would try to take it away from here," he said. "It's just too hot. I'm just a little worried that they're going to stomp all over Rod Palm."

The canonical shot of an East Asian city is a night skyline studded with towering apartment and office buildings, bright with neon and plastic signage, a landscape of energy and modernity. Another classic image is the same city seen from above, in which identical apartment towers march across the city, spilling out over nearby geography, like stylized soldiers colonizing new territory in a board game. Densely populated dynamic conurbations of money, technological innovation and convenience, it is hard to see the cities of East Asia as what they truly are: necropolises. Why is this? The East Asian development model, with

June 16 to June 22 The following flyer appeared on the streets of Hsinchu on June 12, 1895: “Taipei has already fallen to the Japanese barbarians, who have brought great misery to our land and people. We heard that the Japanese occupiers will tax our gardens, our houses, our bodies, and even our chickens, dogs, cows and pigs. They wear their hair wild, carve their teeth, tattoo their foreheads, wear strange clothes and speak a strange language. How can we be ruled by such people?” Posted by civilian militia leader Wu Tang-hsing (吳湯興), it was a call to arms to retake

Desperate dads meet in car parks to exchange packets; exhausted parents slip it into their kids’ drinks; families wait months for prescriptions buy it “off label.” But is it worth the risk? “The first time I gave him a gummy, I thought, ‘Oh my God, have I killed him?’ He just passed out in front of the TV. That never happens.” Jen remembers giving her son, David, six, melatonin to help him sleep. She got them from a friend, a pediatrician who gave them to her own child. “It was sort of hilarious. She had half a tub of gummies,

The wide-screen spectacle of Formula One gets a gleaming, rip-roaring workout in Joseph Kosinski’s F1, a fine-tuned machine of a movie that, in its most riveting racing scenes, approaches a kind of high-speed splendor. Kosinski, who last endeavored to put moviegoers in the seat of a fighter jet in Top Gun: Maverick, has moved to the open cockpits of Formula One with much the same affection, if not outright need, for speed. A lot of the same team is back. Jerry Bruckheimer produces. Ehren Kruger, a co-writer on Maverick, takes sole credit here. Hans Zimmer, a co-composer previously, supplies the thumping