Chinese literati of 700 years ago were not much different from their contemporary counterparts. They trained in literature and philosophy, "loved good houses, nice clothes, delicacies, night life, going to entertainments, collecting vintage items ..." Ming dynasty prose writer Zhang Dai (

As Literati Aesthetics in the 21st Century, (

The literati painters in the past set themselves apart from those producing meticulously realistic works for the imperial academy. While earning their bread on government jobs, they sublimated their longing for an idyllic life away from the treacherous world of politics to express themselves in ink and paper.

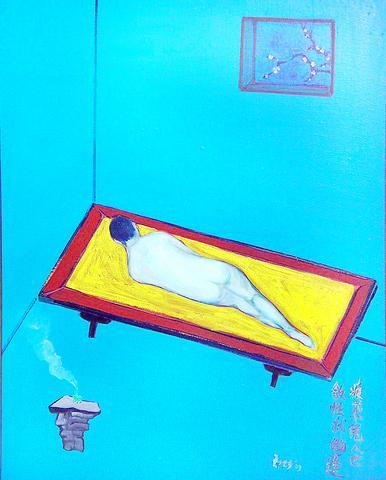

PHOTO COURTESY OF JEFF HSU'S ART

The works of 10 of the contemporary artists in the exhibition constitute a wide range of genres, from oil painting, furniture/sculpture, installation, to traditional ink painting and calligraphy. As ancient literati artists enthused about their moods and enjoyments in the tranquility of their homes, today's literati artists are more self-absorbed and express that through depicting the apparently uneventful surroundings of their lives.

"The transition into a new century sounds an alarm for traditional literati. Paper fans [a favorite medium in the past] have been replaced by air conditioners. The prevalence of computers made ink brushes useful only for a few calligraphy die-hards. The onslaught of technology and a transformed, Westernized society are testing the traditional literati lifestyle," writes curator Michael Chen (

At first glance, the works are all flowers and mountains, but in their respective choice of media and styles, they are all attempts to solve the traditional/modern and Chinese/Western conflicts.

Lin Chuan-chu (

Chen Kun-de (

Extension of the Unusual combines two studies of popular Sung dynasty subjects -- a gentleman on a horse and a dancing lady. What prevents the Sung man and the woman from catching sight of each other is an expanse of meadow on top of today's Yangmingshan. A stray zebra also betrays the post-modernist era in which Chen made the work.

Cheng Tzai-dong's (

"Literati Aesthetics in the 21st Century" will run until Oct. 5 at Jeff Hsu's Art, B1, 1, Ln 200, Sungteh Rd. (台北松德路200巷1號B1).

Growing up in a rural, religious community in western Canada, Kyle McCarthy loved hockey, but once he came out at 19, he quit, convinced being openly gay and an active player was untenable. So the 32-year-old says he is “very surprised” by the runaway success of Heated Rivalry, a Canadian-made series about the romance between two closeted gay players in a sport that has historically made gay men feel unwelcome. Ben Baby, the 43-year-old commissioner of the Toronto Gay Hockey Association (TGHA), calls the success of the show — which has catapulted its young lead actors to stardom -- “shocking,” and says

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) invaded Vietnam in 1979, following a year of increasingly tense relations between the two states. Beijing viewed Vietnam’s close relations with Soviet Russia as a threat. One of the pretexts it used was the alleged mistreatment of the ethnic Chinese in Vietnam. Tension between the ethnic Chinese and governments in Vietnam had been ongoing for decades. The French used to play off the Vietnamese against the Chinese as a divide-and-rule strategy. The Saigon government in 1956 compelled all Vietnam-born Chinese to adopt Vietnamese citizenship. It also banned them from 11 trades they had previously

Inside an ordinary-looking townhouse on a narrow road in central Kaohsiung, Tsai A-li (蔡阿李) raised her three children alone for 15 years. As far as the children knew, their father was away working in the US. They were kept in the dark for as long as possible by their mother, for the truth was perhaps too sad and unjust for their young minds to bear. The family home of White Terror victim Ko Chi-hua (柯旗化) is now open to the public. Admission is free and it is just a short walk from the Kaohsiung train station. Walk two blocks south along Jhongshan

Snoop Dogg arrived at Intuit Dome hours before tipoff, long before most fans filled the arena and even before some players. Dressed in a gray suit and black turtleneck, a diamond-encrusted Peacock pendant resting on his chest and purple Chuck Taylor sneakers with gold laces nodding to his lifelong Los Angeles Lakers allegiance, Snoop didn’t rush. He didn’t posture. He waited for his moment to shine as an NBA analyst alongside Reggie Miller and Terry Gannon for Peacock’s recent Golden State Warriors at Los Angeles Clippers broadcast during the second half. With an AP reporter trailing him through the arena for an