The large-scale import of inexpensive wood carvings from China and Southeast Asian countries over the past decade has made the lives of Taiwanese wood carvers difficult.

In Sanyi (

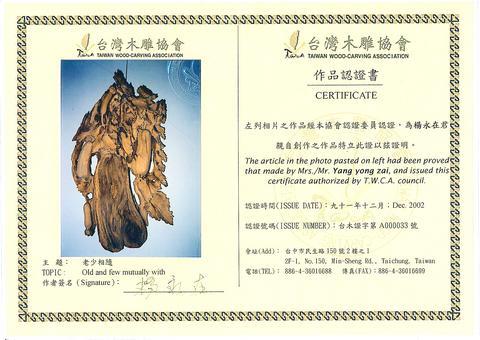

To differentiate between original Taiwanese wood carvings and the often mass produced versions on the market, the Taiwan Wood-carving Association (

Wood carvings made in Taiwan range from several thousand NT dollars to several million, with most works costing from NT$30,000 to NT$150,000. A busy wood carver can earn around NT$2,000 a day. Chinese wood carvers typically earn 30 times less than this (around NT$67).

"A country's wood carvings gradually evolve from handicraft level to the level of art. Chinese wood carvings are still at the handicraft stage. What we see on the market are mostly factory-manufactured products. However, their low prices have caused Taiwanese wood carvers to suffer economically," said Yang Yung-tzai (

Association (TWCA).

"Over the past decade, many local wood carvers have gone to China and set up factories there producing handicraft-level works. Those who did not go learned to refine their craft into works of art," Yang said.

There is also a large number of wood carvings of dubious origin sold at retail stores. Yang said that some of these are commissioned by local wood carvers to be produced by factories in China, while others are unauthorized Chinese imitations of works by popular local artists. One wood carver even submitted a Chinese-made work to participate in the National Literature and Art Achievement Award (

To help combat the problem of fakes, certificates of authenticity for wood carving works have been introduced by the TWCA to show that the works were made in the country, from start to finish, by a Taiwanese artist. They also detail the materials used. Though a neglected aspect for collectors, materials are important for pricing a work. Taiwanese beech timber, for example, is 20 times the price of its Vietnamese or Laotian counterparts.

Faking it

In the past, the only proof of a wood carving's authenticity were privately printed certificates that some stores and artists attached to the works. The most widespread device to prove that a carving is genuine, however, is the autograph, which, Yang said, can easily be faked.

To get a certificate of authenticity, judges and wood craftsmen at TWCA examine the carving styles, techniques and "artistic spirit," to determine whether or not the work was made abroad. A copy of the certificate is kept at the association's office for the reference of doubtful buyers. The association has issued 200 certificates so far, each costing the creator NT$600. There is no refund for failed applications and less than 2 percent of applications fail to gain certification.

Shen Pei-tze (

"I used to give my buyers a certificate I made and I always carved my autograph on the works. But these can still be copied. Having a third party certificate for my works is a much better solution."

Others are not so sure. Lin Chin-chang (

For genuine artists, Lin went on, the best guarantee is the artists themselves. "If a wood carver has an unmistakable style, his or her name naturally becomes a brand, like Ju Ming (朱銘) in the sculpture circle. People recognize that brand."

Like most Sanyi wood carvers, Lin sells his works directly to collectors. So far, they have not required certificates from Lin. "I have been making wood carvings for over a decade, but the association has been around for less than a year. I think I am in a better position to guarantee my works."

Making it

Lin said there had been no disputes regarding the authenticity of his works so far.

Other well known wood carvers have come up with different ways to prove the authenticity of their works to collectors. Huang Ma-ching (

"A wood carving that has been featured at exhibitions has few problems with establishing its authenticity. I have had no authenticity troubles so far," said Huang, who nevertheless admitted there is a large number of copies of his works on the market.

The application fee, Huang said, discouraged him from applying for a certificate. "My works do not cater to the market, so that usually out of 100 works I have done, I can only sell a few of them. The situation is even worse these days because of the recession. Certificates may be a good thing for more commercial wood carvings, but it makes little difference to me."

Despite the mixed response, Yang is intent on making the system last.

"When Chinese factories stamp `Made in Taiwan' on their wood products to raise their price, issuing the certificates is an act of self-help," Yang said. "Both mass manufactured products and art crafts need guarantees of their origin and authenticity.

"We chose to keep our roots in Taiwan when others sought development in China. [Last year,] before the government did anything about the economic crisis we are facing, we launched this system to help ourselves."

But, six months after the launch of the certification scheme, government authorities are catching up. The Council for Cultural Affairs (

The certificate for ceramic works is scheduled to be launched at the end of this year, according to Lu Chia-ching, chief executive of the Chinese Ceramic Association (

Proving it

"Unlike wood carvings, the ceramic circle has seen few disputes over the origin of ceramic works, but there are confusing standards of quality. The certificate will mark those works deemed above standard quality," Lu said.

The TWCA, meanwhile, believes it is on to a good thing with the certification scheme, but needs to convince wood carving artists the idea is sound.

"What artists do not yet seem to understand is that this is a guarantee of their intellectual property rights. Collectors may not have doubts about the origin of their collection today, but a dispute may arise decades afterward. The wood carving circle needs to promote the protection of intellectual property rights," Yang said.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Lines between cop and criminal get murky in Joe Carnahan’s The Rip, a crime thriller set across one foggy Miami night, starring Matt Damon and Ben Affleck. Damon and Affleck, of course, are so closely associated with Boston — most recently they produced the 2024 heist movie The Instigators there — that a detour to South Florida puts them, a little awkwardly, in an entirely different movie landscape. This is Miami Vice territory or Elmore Leonard Land, not Southie or The Town. In The Rip, they play Miami narcotics officers who come upon a cartel stash house that Lt. Dane Dumars (Damon)

Today Taiwanese accept as legitimate government control of many aspects of land use. That legitimacy hides in plain sight the way the system of authoritarian land grabs that favored big firms in the developmentalist era has given way to a government land grab system that favors big developers in the modern democratic era. Articles 142 and 143 of the Republic of China (ROC) Constitution form the basis of that control. They incorporate the thinking of Sun Yat-sen (孫逸仙) in considering the problems of land in China. Article 143 states: “All land within the territory of the Republic of China shall