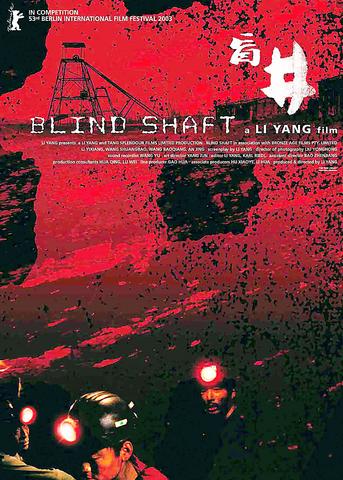

This year's Berlin Film Festival may be a disappointing one for Chinese-language films, but perhaps a very promising beginning for Chinese director Li Yang (李楊) and his German-Chinese co-production Blind Shaft (盲井).

The film earned Li a Silver Bear for artistic contribution at the festival, making it one of only two Chinese-language films to win an award at the 2003 Berlinale (the other being Zhang Yi-mou's Hero).

PHOTO COURTESY OF THE FILM LIBRARY

Unlike Hero, with its stunning cinematography and fancy kung fu, Blind Shaft is a realistic drama portraying the dangerous coal mines and the equally dangerous human behaviors of greed, treachery and murder.

This documentary-like film is Li's feature film debut, and it made an impressive appearance in the Berlinale's competition section, both in its revelation of the harsh life at the bottom rungs of Chinese society and in its comic twist at the end of the story.

In China, there are reportedly 7,000 coal miners killed in accidents each year. And in many cases, miners' bodies are cremated and buried without the victim's families ever being notified.

The circumstances surrounding these accidents -- the most famous of which occurred in Guangxi in 2001 -- are rarely made public, as many mines are illegal and corrupt local officials (who take bribes from the mines' owners) do not want such details made public.

Li Yang's film is a fictionalized account of one such accident. Two mine workers in a run-down illegal mine have killed one of their fellow miners, a man they had previously introduced to the job as their "relative." They make the death look like an accident and extort compensation from the mine's owner for the death of their "relative," threatening to report the accident to the public.

Returning home with their loot, the two murderers seek another victim. This time they find a 16-year-old peasant boy. The two ask him to introduce himself to the mine's management as a relative of theirs, because they say it will be easier for him to get a job that way. The real scheme is to arrange another accidental death and demand compensation for another deceased "family member."

"What is portrayed here is no deliberate melodrama or dramatization. It's a real story," said the 44-year-old director, who has made three documentaries prior to this feature film.

Making the movie was nearly as hazardous a venture as mining. As many of the owners of illegal mines and corrupt bureaucrats would not have welcomed an effort to dig up the dirt on their businesses, Li and his crew were risking their lives when they filmed 700m underground in the mines of Shaanxi Province.

"One time, I was surrounded by the owners of a mine and [armed] police, and they threatened to take me away," Li said. And of course, the film is banned in China, something which has given it a higher profile abroad.

After Berlin, Blind Shaft goes to Cannes to be screened in the Director's Fortnight section and is expected to be distributed throughout Asia, with one notable exception.

The canonical shot of an East Asian city is a night skyline studded with towering apartment and office buildings, bright with neon and plastic signage, a landscape of energy and modernity. Another classic image is the same city seen from above, in which identical apartment towers march across the city, spilling out over nearby geography, like stylized soldiers colonizing new territory in a board game. Densely populated dynamic conurbations of money, technological innovation and convenience, it is hard to see the cities of East Asia as what they truly are: necropolises. Why is this? The East Asian development model, with

June 16 to June 22 The following flyer appeared on the streets of Hsinchu on June 12, 1895: “Taipei has already fallen to the Japanese barbarians, who have brought great misery to our land and people. We heard that the Japanese occupiers will tax our gardens, our houses, our bodies, and even our chickens, dogs, cows and pigs. They wear their hair wild, carve their teeth, tattoo their foreheads, wear strange clothes and speak a strange language. How can we be ruled by such people?” Posted by civilian militia leader Wu Tang-hsing (吳湯興), it was a call to arms to retake

Desperate dads meet in car parks to exchange packets; exhausted parents slip it into their kids’ drinks; families wait months for prescriptions buy it “off label.” But is it worth the risk? “The first time I gave him a gummy, I thought, ‘Oh my God, have I killed him?’ He just passed out in front of the TV. That never happens.” Jen remembers giving her son, David, six, melatonin to help him sleep. She got them from a friend, a pediatrician who gave them to her own child. “It was sort of hilarious. She had half a tub of gummies,

The wide-screen spectacle of Formula One gets a gleaming, rip-roaring workout in Joseph Kosinski’s F1, a fine-tuned machine of a movie that, in its most riveting racing scenes, approaches a kind of high-speed splendor. Kosinski, who last endeavored to put moviegoers in the seat of a fighter jet in Top Gun: Maverick, has moved to the open cockpits of Formula One with much the same affection, if not outright need, for speed. A lot of the same team is back. Jerry Bruckheimer produces. Ehren Kruger, a co-writer on Maverick, takes sole credit here. Hans Zimmer, a co-composer previously, supplies the thumping