In 1603, Dutch ships ventured into the waters of the South China Sea searching for a base from which to open trade with China. They bore the commission and the guns of the then one-year-old Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC), or the Dutch East India Company, which was working out of a new base in Batavia (now Jakarta), through which it would funnel nearly all Asian trade for the next 200 years.

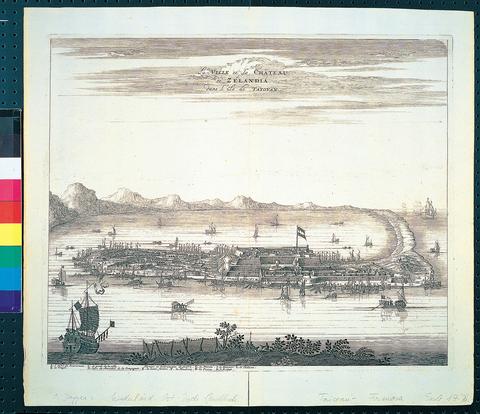

But access to the riches of East Asia wasn't easy. After Ming dynasty forces kicked the Dutch out of what is now Penghu for the second time in 1624, the European traders were allowed to take possession of a larger island beyond the Penghu archipelago to the west. They settled near present day Tainan on a sandbar islet that they inferred from local speech was called "Tayouan" or "Taywan." The name was eventually used to identify the entire island, but did it also produce an identity?

A case for this historical origin of Taiwan -- and by this I don't just mean an Aboriginal word for some sandbar, but instead the international perception of Taiwan as a place distinct from China -- is advocated in The Birth of Taiwan: Formosa in the Seventeenth Century (

Two years in the planning, the exhibition focuses on the Taiwan of the Dutch colonial era (1624-1662), taking full advantage of the VOC's rich legacy of historical records, maps, trade wares and other sundry artifacts. Its contents include more than 270 pieces from more than 35 museums in Taiwan and Europe. Several are rare and fascinating finds, like a handwritten dictionary that translates Aboriginal names from Sinkanese, a Dutch romanization of an Aboriginal language, into Chinese characters.

The lexicon is just one of many details of a show that offers the most complete and interesting picture of Dutch-occupied Taiwan ever exhibited locally, or for that matter, probably anywhere in the world.

At the time of the Dutch arrival in 1624, little was known about Taiwan. China's court records produced conflicting accounts, and the Portuguese, who never really spent much time in Taiwan even though they christened the "Ihla Formosa" after spying it from a ship three-quarters of a century earlier, depicted it on their maps as a string of three separate islands. Taiwan was not mapped as a single body by Europeans until the first Dutch governor of Taiwan, a man named Snock, in 1625 sent the cartographer Nordeloos to circumnavigate his new territory and map the coastline.

But maps are only one topic explored. Another major element is the introduction of Dutch trade and technology and the transformations that ensued. Under the guidance of a group known as the Seventeen Gentlemen, the VOC's directors in Amsterdam, Taiwan became a Dutch transit hub with major links to both China and Japan. It moved Chinese silks and porcelain, Indonesian pepper and Japanese silver. Taiwan's sugarcane, silk, and skins of the abundant Formosan deer, whose hides were used by the Japanese in the manufacture of samurai armor.

Dutch journals and engravings show an ethnographic interest in the native Formosans, the Aborigines of the Pingpu (平埔) tribe. There were few Chinese settlers in the Taiwan of the 1620s, though by the time the Dutch left that had changed. In a push for development, the new colonists introduced European-style agriculture and imported water buffaloes and plows from China. Han Chinese colonists followed. There were an estimated 40,000 of them by 1662, the year the Dutch were expelled at the hands of Koxinga (鄭成功).

Koxinga was a pirate warlord who rebelled against the encroaching Manchus, maintaining loyalty to the Ming even after the 1644 suicide of its last emperor, Chung Chen (崇禎). In the years that followed he continued to foment resistance in southern China, but a 1659 defeat forced his 1661 retreat to Taiwan. He landed with an army of 25,000 and immediately contested the Dutch, laying siege to the Dutch fort of Zeelandia at Tainan. The Dutch held out for nine months at the cost of 1,600 lives before signing a treaty that allowed them to leave peaceably with the majority of their possessions.

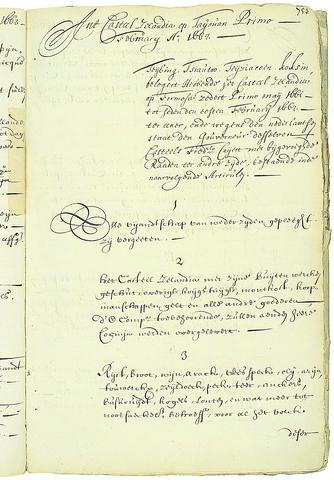

The treaty, an impressive tome of compiled Dutch records from much of the occupation, is on display, as are the 18 terms of surrender proposed by Governor Frederick Coyett and the 16 eventually accepted by Koxinga. The first of them states that both parties shall renounce hostilities and forget all previous conflicts. Predictably, this never happened. A year later, the Dutch returned with 16 men-of-war in an attack that was repelled, and as recently as the fall of 2001, Taiwanese baseball fans were still waving placards bearing Koxinga's likeness while Taiwan and the Netherlands squared off in the 2001 Baseball World Cup.

Unfortunately the exhibition basically ends with the Coyett's 1662 surrender. There is little mention of the Spanish presence in northern Taiwan at Tamsui from 1624-1642 or the Kingdom of Taiwan, which existed under Koxinga's heirs from 1662-1683, ending with the conquest of Taiwan by the Qing. The absences can be accounted for by scarcity of records from those segments of history, especially in comparison to the abundance of VOC records now scattered throughout the world's museums. Also, as the show makes a case for the birth of Taiwan that was separate from China, it would probably not want to finish off with the actual conclusion of the 17th century, a Taiwan under Chinese rule.

The Birth of Taiwan: Formosa in the Seventeenth Century is on display through April 30 at the National Palace Museum (

One of the biggest sore spots in Taiwan’s historical friendship with the US came in 1979 when US president Jimmy Carter broke off formal diplomatic relations with Taiwan’s Republic of China (ROC) government so that the US could establish relations with the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Taiwan’s derecognition came purely at China’s insistence, and the US took the deal. Retired American diplomat John Tkacik, who for almost decade surrounding that schism, from 1974 to 1982, worked in embassies in Taipei and Beijing and at the Taiwan Desk in Washington DC, recently argued in the Taipei Times that “President Carter’s derecognition

This year will go down in the history books. Taiwan faces enormous turmoil and uncertainty in the coming months. Which political parties are in a good position to handle big changes? All of the main parties are beset with challenges. Taking stock, this column examined the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) (“Huang Kuo-chang’s choking the life out of the TPP,” May 28, page 12), the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) (“Challenges amid choppy waters for the DPP,” June 14, page 12) and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) (“KMT struggles to seize opportunities as ‘interesting times’ loom,” June 20, page 11). Times like these can

June 23 to June 29 After capturing the walled city of Hsinchu on June 22, 1895, the Japanese hoped to quickly push south and seize control of Taiwan’s entire west coast — but their advance was stalled for more than a month. Not only did local Hakka fighters continue to cause them headaches, resistance forces even attempted to retake the city three times. “We had planned to occupy Anping (Tainan) and Takao (Kaohsiung) as soon as possible, but ever since we took Hsinchu, nearby bandits proclaiming to be ‘righteous people’ (義民) have been destroying train tracks and electrical cables, and gathering in villages

Dr. Y. Tony Yang, Associate Dean of Health Policy and Population Science at George Washington University, argued last week in a piece for the Taipei Times about former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) leading a student delegation to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) that, “The real question is not whether Ma’s visit helps or hurts Taiwan — it is why Taiwan lacks a sophisticated, multi-track approach to one of the most complex geopolitical relationships in the world” (“Ma’s Visit, DPP’s Blind Spot,” June 18, page 8). Yang contends that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has a blind spot: “By treating any