In global climate policy, the ocean was long treated as an afterthought, too vast to manage effectively and too resilient to be degraded. Instead, the focus was almost exclusively on reducing greenhouse-gas (GHG) emissions and preserving forests. That era is now over.

At the most recent UN Climate Change Conference (COP30) in Belem, Brazil, the ocean moved from the margins to the mainstream of climate governance. It featured prominently in national climate plans, adaptation frameworks, the follow-up to the first “global stocktake” under the Paris climate agreement and even the evolving architecture of climate finance.

This shift in the global agenda was likely inevitable, as the ocean increasingly suffers the effects of absorbing more than 90 percent of the excess heat trapped by GHGs and about one-quarter of annual carbon dioxide emissions. The consequences include warming, acidification, deoxygenation, collapsing fisheries, and coastal erosion. Small island developing states (SIDS) and least developed countries (LDCs), many of which are extremely vulnerable to sea-level rise, accelerated the shift by framing ocean governance as a matter not just of environmental management, but of survival and justice.

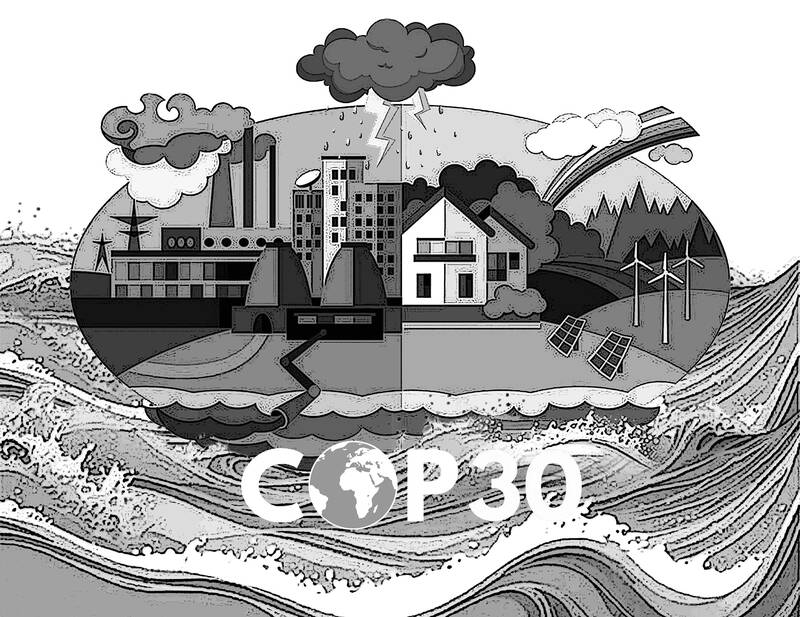

Illustration: Constance Chou

Consider, for example, COP30’s headline political declaration, the Global Mutirao, which frames climate change, biodiversity loss, and land and ocean degradation as interconnected crises demanding shared solutions and collective action. It explicitly recognizes the role of marine ecosystems in climate stability and sustainable development, giving governments the political cover to integrate ocean and coastal issues into their national climate strategies, development plans and funding proposals.

A new baseline has been established. For the first time in the UN climate process, the official synthesis of national climate plans contains a section dedicated to the ocean. Roughly three-quarters of these national plans include marine references, such as blue carbon, offshore renewables, fisheries resilience and maritime decarbonization. The next step is to move toward quantified ocean-based targets, measurable blue-carbon accounting and concrete investment pledges for coastal communities.

At COP30, governments also adopted the Belam Adaptation Indicators to track action and progress under the Global Goal on Adaptation. While these indicators are sector-neutral, they are still highly relevant to the health of coastal ecosystems, the resilience of fisheries, the vulnerability of coastal infrastructure and livelihoods, and early-warning coverage. Crucially, climate funds — including the Green Climate Fund, the Global Environment Facility and the Adaptation Fund — have been encouraged to align their support with these indicators. This could give rise to a new generation of bankable ocean-adaptation projects.

Moreover, ocean-based solutions are attracting more resources. The One Ocean Partnership, which launched at COP30, aims to mobilize US$20 billion for coastal resilience, blue-carbon ecosystems and ocean protection; create 20 million blue jobs worldwide; and restore 20 million hectares of marine ecosystems by 2030. More consequential was the UN Standing Committee on Finance’s announcement that its forum this year would focus on financing climate action in water systems and the ocean — a formal push for blue investment that would have been unthinkable a decade ago.

However, treaties and conferences are no longer the only means for creating climate obligations. International law has started to converge with climate science. In 2024, the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea ruled that GHG emissions constitute marine pollution under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. Last year, the International Court of Justice affirmed that states have a binding legal duty to prevent foreseeable climate harm.

This legal evolution would be important for disputes over state conduct at sea, particularly as the world confronts the next frontier of climate intervention: marine carbon dioxide removal. Techniques such as alkalinity enhancement and large-scale algal cultivation might eventually contribute to net-zero strategies, but they could pose ecological risks and currently exist in a fragmented regulatory landscape. In the absence of coordinated ocean governance, unilateral experimentation could trigger transboundary effects and conflict.

As influence continues to shift away from traditional power centers (a trend on display at COP30), and as SIDS and LDCs increasingly shape global climate norms, ocean and coastal resilience would continue to gain prominence in policy debates. Even advanced economies have begun to realize the importance of a sustainable approach to marine resources and ocean management, with the G20 establishing Oceans 20, a group focused on this goal, under Brazil’s presidency in 2024.

The design of COP31 points toward a new geopolitical landscape: Australia and Turkey will colead the conference, while a pre-COP gathering would be held on a Pacific Island state with Australian support. This has raised hopes that it could be the first truly “blue” COP. In that case, ocean-based targets and action would become even more important in national climate strategies, global stocktake metrics, climate-finance rules and technology-transfer systems over the next few years.

In fact, the maritime century might be upon us. The ocean is the planet’s largest carbon sink, the backbone of global trade, a critical source of food and energy, and the frontline of climate vulnerability. It is also becoming a site of strategic competition for data, technology, resources and legal leverage.

The climate’s fate depends on what happens to the ocean, and fragmented mandates, outdated treaties and siloed financing are no longer sufficient to ensure its health. The question is whether institutions can evolve quickly enough to establish the durable, equitable and effective governance structures required for safeguarding this critical planetary system.

Kilaparti Ramakrishna is senior advisor to the president and director on ocean and climate policy at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

We are used to hearing that whenever something happens, it means Taiwan is about to fall to China. Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) cannot change the color of his socks without China experts claiming it means an invasion is imminent. So, it is no surprise that what happened in Venezuela over the weekend triggered the knee-jerk reaction of saying that Taiwan is next. That is not an opinion on whether US President Donald Trump was right to remove Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro the way he did or if it is good for Venezuela and the world. There are other, more qualified

This should be the year in which the democracies, especially those in East Asia, lose their fear of the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) “one China principle” plus its nuclear “Cognitive Warfare” coercion strategies, all designed to achieve hegemony without fighting. For 2025, stoking regional and global fear was a major goal for the CCP and its People’s Liberation Army (PLA), following on Mao Zedong’s (毛澤東) Little Red Book admonition, “We must be ruthless to our enemies; we must overpower and annihilate them.” But on Dec. 17, 2025, the Trump Administration demonstrated direct defiance of CCP terror with its record US$11.1 billion arms

The immediate response in Taiwan to the extraction of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro by the US over the weekend was to say that it was an example of violence by a major power against a smaller nation and that, as such, it gave Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) carte blanche to invade Taiwan. That assessment is vastly oversimplistic and, on more sober reflection, likely incorrect. Generally speaking, there are three basic interpretations from commentators in Taiwan. The first is that the US is no longer interested in what is happening beyond its own backyard, and no longer preoccupied with regions in other

As technological change sweeps across the world, the focus of education has undergone an inevitable shift toward artificial intelligence (AI) and digital learning. However, the HundrED Global Collection 2026 report has a message that Taiwanese society and education policymakers would do well to reflect on. In the age of AI, the scarcest resource in education is not advanced computing power, but people; and the most urgent global educational crisis is not technological backwardness, but teacher well-being and retention. Covering 52 countries, the report from HundrED, a Finnish nonprofit that reviews and compiles innovative solutions in education from around the world, highlights a