US President Donald Trump spent much of the last week of last month in Asia. He managed to bring about ceasefires on several fronts of a trade war largely of his own making, after imposing tariffs on friends and foes alike. What he did not do was create enduring structures in the economic sphere or put to rest increasing doubts about the US’ strategic commitment to the region.

To be sure, there were some valuable accomplishments. Trump’s meetings in Japan, arguably the most important US ally nowadays by virtue of its economic and military heft, and its critical role in balancing a stronger and more assertive China, went as well or better than anyone could have hoped. A hallmark of the Trump administration’s foreign policy is to be tough on friends and allies, but Trump and Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi got off to an excellent start.

It helped that Takaichi was closely associated with former Japanese prime minister Abe Shinzo, the foreign leader who built the closest relationship with Trump during his first term as president. It also helped that Japan is spending more on defense and is offering to substantially increase its investment in the US.

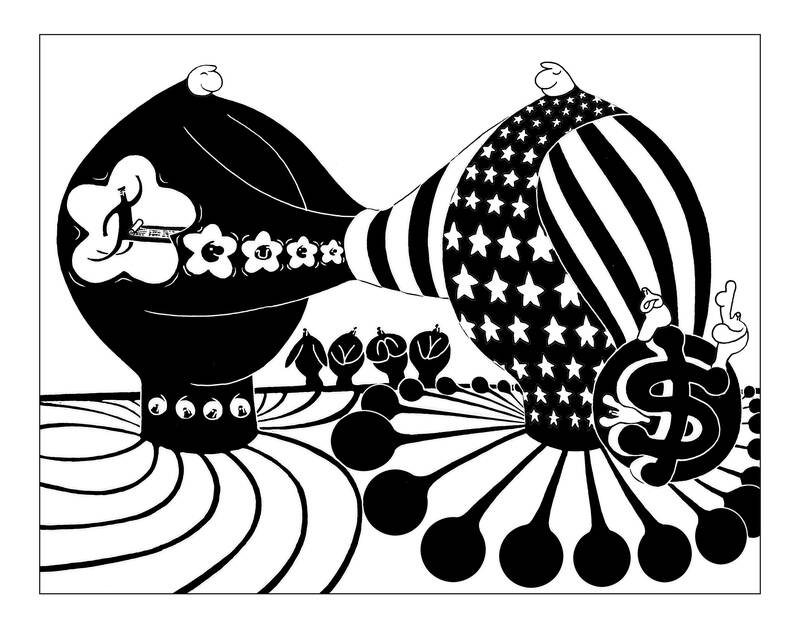

Illustration: Mountain People

The US and South Korea also managed to put their economic relationship on a better footing. Clearly, Washington’s allies in Asia as in Europe have got better at managing the often-difficult diplomatic dance with Trump. Flattery, gifts and fanfare, packaged with increases in defense spending and investment in the US, can make for a successful visit.

The positive tone of these meetings made for a strong backdrop to the bilateral session between Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平). The meeting produced something of a truce in the US-China trade war, but did not resolve the underlying economic frictions or address the growing geopolitical tensions between the world’s two biggest economies.

China would resume some modest purchases of US soybeans, has promised to rein in exports of chemicals used to make fentanyl, and would postpone restrictions on rare earth exports for one year.

The US, for its part, would reduce overall tariffs on Chinese goods from 57 percent to 47 percent. A deal on the social media app TikTok appears close to being finalized. New export controls limiting what advanced US technology can go to China seem to have been put on hold.

However, a truce is not permanent peace. Trade issues could and probably would resurface, much as they recently have between the US and Canada when Trump was angered by a television spot put out by Ontario’s government that quoted former US president Ronald Reagan’s criticisms of tariffs. Moreover, owing to the dependence of many US companies’ supply chains on access to Chinese minerals and components, China retains important leverage over the US that could be brought to bear amid any crisis.

Perhaps more important, what did not emerge from the Trump-Xi meeting is any comprehensive rationale for this era of US-China relations, one that governs not just trade and investment, but also geopolitical differences. No surprise, then, that these talks ended with no common understanding about Taiwan, while China’s purchases of Russian energy and support for Russia’s military would continue. While these issues are sure to come up and even dominate Trump’s announced visit to China in April next year, progress is far from guaranteed.

There was a palpable sense of relief in the region that the US-China economic relationship emerged slightly more stable, as no one wants to be forced to choose between the two great powers. For many, China is their largest trading partner and a military force to be reckoned with. At the same time, many Indo-Pacific countries are dependent on the US for their security and economic wellbeing.

However, not everything went well in the region during Trump’s stay. US relations with Vietnam, like those with India, have taken a turn for the worse. China would be the principal beneficiary of this distancing between the US and countries that could complicate Chinese defense planning. More generally, the US has hurt its standing with many countries in the region by refusing to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, the region’s signature trade pact, and by Trump’s liberal use of tariffs.

Many are also uncomfortable about developments within the US. The federal government shutdown reflects a country so divided that it cannot function effectively, a view already made widespread by the government’s inability to deal with the country’s ballooning debt. Likewise, severe restrictions on immigration, reductions in federal research funding, and attacks on universities raise questions about long-term US competitiveness and reliability.

Most unnerving of all are trends in US foreign policy. Washington’s inconsistency toward backing Ukraine and its softness toward Russia have created fears that the US would choose a similar approach for dealing with Taiwan (and the South China Sea) and China.

Nor can the US’ friends and allies in Asia make sense of US military action off the coast of Venezuela in an effort that appears designed to bring down Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro’s regime, the Trump administration’s deployment of the US National Guard in US cities, and pressures on Panama’s government to cede control of the Panama Canal. Announced intentions to reduce the number of US troops in Europe would add to the impression of a US foreign policy in transition.

One could be forgiven for concluding that the pivot to Asia begun by former US president Barack Obama has been replaced by a pivot to the Western Hemisphere. Needless to say, this is not the pivot the US’ friends and allies in Asia were and are counting on.

Richard Haass, president emeritus of the Council on Foreign Relations, is a senior counselor at Centerview Partners, distinguished university scholar at New York University, and the author of the weekly Substack newsletter Home & Away.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

Donald Trump’s return to the White House has offered Taiwan a paradoxical mix of reassurance and risk. Trump’s visceral hostility toward China could reinforce deterrence in the Taiwan Strait. Yet his disdain for alliances and penchant for transactional bargaining threaten to erode what Taiwan needs most: a reliable US commitment. Taiwan’s security depends less on US power than on US reliability, but Trump is undermining the latter. Deterrence without credibility is a hollow shield. Trump’s China policy in his second term has oscillated wildly between confrontation and conciliation. One day, he threatens Beijing with “massive” tariffs and calls China America’s “greatest geopolitical

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairwoman Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) made the astonishing assertion during an interview with Germany’s Deutsche Welle, published on Friday last week, that Russian President Vladimir Putin is not a dictator. She also essentially absolved Putin of blame for initiating the war in Ukraine. Commentators have since listed the reasons that Cheng’s assertion was not only absurd, but bordered on dangerous. Her claim is certainly absurd to the extent that there is no need to discuss the substance of it: It would be far more useful to assess what drove her to make the point and stick so

The central bank has launched a redesign of the New Taiwan dollar banknotes, prompting questions from Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) legislators — “Are we not promoting digital payments? Why spend NT$5 billion on a redesign?” Many assume that cash will disappear in the digital age, but they forget that it represents the ultimate trust in the system. Banknotes do not become obsolete, they do not crash, they cannot be frozen and they leave no record of transactions. They remain the cleanest means of exchange in a free society. In a fully digitized world, every purchase, donation and action leaves behind data.

Yesterday, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), once the dominant political party in Taiwan and the historic bearer of Chinese republicanism, officially crowned Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) as its chairwoman. A former advocate for Taiwanese independence turned Beijing-leaning firebrand, Cheng represents the KMT’s latest metamorphosis — not toward modernity, moderation or vision, but toward denial, distortion and decline. In an interview with Deutsche Welle that has now gone viral, Cheng declared with an unsettling confidence that Russian President Vladimir Putin is “not a dictator,” but rather a “democratically elected leader.” She went on to lecture the German journalist that Russia had been “democratized