Most people have encountered “AI slop,” the deluge of low-quality content produced by generative artificial intelligence (AI) tools that has inundated the Internet, but is this computer-made hogwash taking over work as well?

News that Deloitte Australia would partially refund the government for a report sprinkled with apparent AI-generated errors has caused a local furor and spurred international headlines.

Australian Senator Barbara Pocock said in a radio interview that the A$440,000 (US$287,001) taxpayer-funded document misquoted a judge and cited nonexistent references.

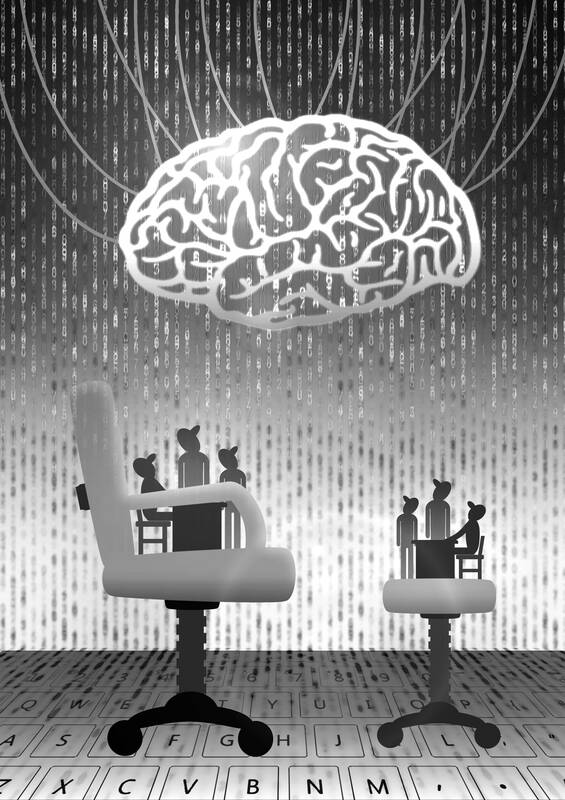

Illustration: Yusha

The alleged AI mistakes are “the kinds of things that a first-year university student would be in deep trouble for,” she said.

Deloitte Australia did not immediately respond to my request for comment, but has said the corrections did not impact the report’s substance or recommendations, and told other outlets that: “The matter has been resolved directly with the client.”

Besides being a bad look for the Big Four firm at a time when Australians’ trust in government-use of private consulting firms was already fraught, there is a reason it has struck such a nerve.

It has reopened a global debate on the limitations — and high cost — of the technology backfiring in the workplace. It is not the first case of AI hallucinations or chatbots making things up, to surface in viral ways. It likely would not be the last.

The tech industry’s promises that AI would make us all more productive are part of what is propping up their hundreds of billions of dollars in spending, but the jury is still out on how much of a difference it is actually making in the office.

Markets were rattled in August after researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology said that 95 percent of firms surveyed have not seen returns on investments into generative AI. A separate study from McKinsey found that while nearly eight in 10 companies are using the technology, just as many report “no significant bottom-line impact.”

Some of it can be attributed to growing pains as business leaders work out the kinks in the early days of deploying AI in their organizations. Technology companies have responded by putting out their own findings suggesting AI is helping with repetitive office tasks and highlighting its economic value.

However, fresh research suggests some of the tension might be due to the proliferation of “workslop,” which the Harvard Business Review defines as “AI generated work content that masquerades as good work, but lacks the substance to meaningfully advance a given task.” It encapsulates the experience of trying to use AI to help with your job, only to find it has created more work for you or your colleagues.

About 40 percent of US desk workers have received workslop over the past month, a survey from last month from researchers at BetterUp and the Stanford Social Media Lab. The average time it takes to resolve each incident is two hours, and the phenomenon can cost US$9 million annually for a 10,000-person company.

It can also risk eroding trust at the office, something that is harder to rebuild once it is gone. About one-third of people (34 percent) who receive workslop notify their teammates or managers, and about the same share (32 percent) say they are less likely to want to work with the sender in the future, the Harvard Business Review reported.

There are ways to smooth out the transition. Implementing clear policies is essential. Disclosures of when and how AI was used during workflows can also help restore trust. Managers must make sure that employees are trained in the technology’s limitations, and understand that they are ultimately responsible for the quality of their work regardless of whether they used a machine’s assistance. Blaming AI for mistakes just does not cut it.

The growing cases of workslop should also be a broader wake-up call. At this nascent stage of the technology, there are serious hindrances to the “intelligence” part of AI. The tools might seem good at writing because they recognize patterns in language and mimic them in their outputs, but that should not be equated with a true understanding of materials. In addition, they are sycophantic — they are designed to engage and please users — even if that means getting important things wrong.

As mesmerizing as it can be to see chatbots instantaneously create polished slides or savvy-sounding reports, they are not reliable shortcuts. They still require fact-checking and human oversight.

Despite the big assurances that AI will improve productivity, and is thus worth businesses paying big bucks for, people seem to be using it more for lower-stakes tasks. Data suggest that consumers are increasingly turning to these tools outside of the office. A majority of ChatGPT queries (73 percent) in June were non-work related, according to a study published last month from OpenAI’s own economic research team and a Harvard economist. That is up from 53 percent last year.

An irony is that all this might end up being good news for some staff at consulting giants such as the one caught up in the Australia backlash. It turns out AI might not be so good at their jobs just yet.

The more workslop piles up in the office, the more valuable human intelligence would become.

Catherine Thorbecke is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asia tech. Previously she was a tech reporter at CNN and ABC News. This column reflects the personal views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

There is a modern roadway stretching from central Hargeisa, the capital of Somaliland in the Horn of Africa, to the partially recognized state’s Egal International Airport. Emblazoned on a gold plaque marking the road’s inauguration in July last year, just below the flags of Somaliland and the Republic of China (ROC), is the road’s official name: “Taiwan Avenue.” The first phase of construction of the upgraded road, with new sidewalks and a modern drainage system to reduce flooding, was 70 percent funded by Taipei, which contributed US$1.85 million. That is a relatively modest sum for the effect on international perception, and

At the end of last year, a diplomatic development with consequences reaching well beyond the regional level emerged. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu declared Israel’s recognition of Somaliland as a sovereign state, paving the way for political, economic and strategic cooperation with the African nation. The diplomatic breakthrough yields, above all, substantial and tangible benefits for the two countries, enhancing Somaliland’s international posture, with a state prepared to champion its bid for broader legitimacy. With Israel’s support, Somaliland might also benefit from the expertise of Israeli companies in fields such as mineral exploration and water management, as underscored by Israeli Minister of

When former president Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文) first took office in 2016, she set ambitious goals for remaking the energy mix in Taiwan. At the core of this effort was a significant expansion of the percentage of renewable energy generated to keep pace with growing domestic and global demands to reduce emissions. This effort met with broad bipartisan support as all three major parties placed expanding renewable energy at the center of their energy platforms. However, over the past several years partisanship has become a major headwind in realizing a set of energy goals that all three parties profess to want. Tsai

On Sunday, elite free solo climber Alex Honnold — famous worldwide for scaling sheer rock faces without ropes — climbed Taipei 101, once the world’s tallest building and still the most recognizable symbol of Taiwan’s modern identity. Widespread media coverage not only promoted Taiwan, but also saw the Republic of China (ROC) flag fluttering beside the building, breaking through China’s political constraints on Taiwan. That visual impact did not happen by accident. Credit belongs to Taipei 101 chairwoman Janet Chia (賈永婕), who reportedly took the extra step of replacing surrounding flags with the ROC flag ahead of the climb. Just