China’s military has long been accused of reckless behavior in the air and at sea. Last week’s collision between two of its vessels in the South China Sea underscores how a single miscalculation could spark a wider conflict.

At stake is the stability of the Indo-Pacific, a strategically important region for the US, where several of its partners, including Japan, the Philippines and Australia, are increasingly exposed to Beijing’s risky maneuvers.

The latest incident is part of a broader pattern of behavior, especially in the areas China says it owns. Video of the dangerous encounter on Monday last week shows a China Coast Guard ship firing water cannons as it chased a Philippine Coast Guard vessel, before slamming into one of its own warships. Despite the evidence, Beijing blamed Manila for the accident, accusing it of deliberately “intruding” into its waters.

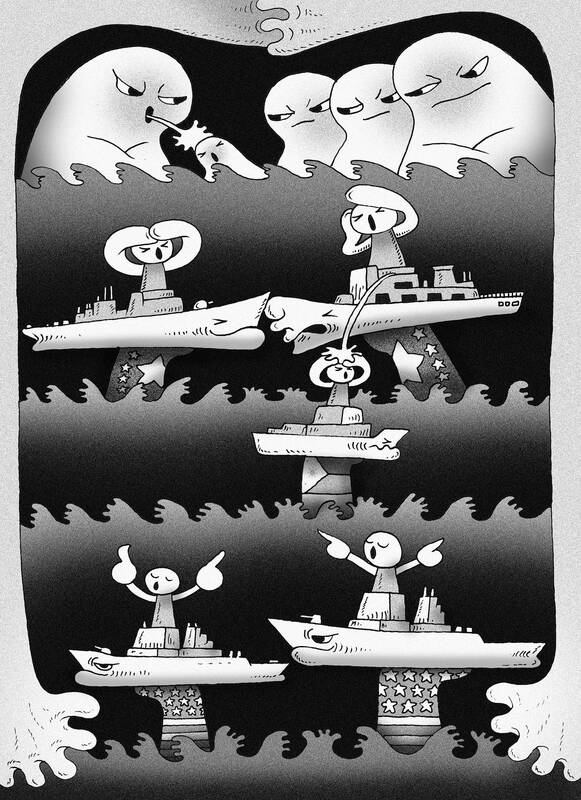

Illustration: Mountain People

China’s strategy of pushing boundaries is also about testing US resolve. The US and the Philippines are treaty allies, with Washington legally obligated to defend Manila if attacked. By escalating encounters at sea just to the brink of confrontation, Beijing is probing whether Washington would stand by that commitment.

China’s repeated harassment of Philippine vessels comes despite a 2016 arbitration ruling in The Hague that sided with the Philippines, declaring Beijing’s historical assertions baseless. China claims more than 80 percent of the lucrative waters and refuses to acknowledge the competing stakes of other Southeast Asian nations.

This assertiveness is not limited to the sea. Beijing regularly deploys warplanes toward Taiwan. One of the most recent high-profile incursions took place in June after US lawmakers visited a top Taiwanese military figure. The tactic appears to have two goals in mind: Exhaust Taipei’s pilots, but also to normalize China’s military presence.

It is also about checking how far Washington would go to defend Taiwan in a crisis. Under US President Donald Trump, there has been little guarantee the US would step in if it were attacked.

Key allies Japan and Australia have felt heightened pressure, too. Last month, Tokyo expressed serious concerns after a Chinese fighter bomber flew within 30m of one of its surveillance planes over the East China Sea. Beijing defended those actions as “justified” and “professional.”

In February, Australia was forced to issue aviation warnings when Chinese naval vessels staged live-fire exercises off its coast, followed by similar drills near New Zealand the next day.

Individually, Beijing can dismiss these incidents as isolated, and insist that it is doing nothing wrong. Combined, they reveal a broader pattern — a calculated strategy to assert dominance while stopping short of outright war, as the RAND Corp, a California-based think tank said in a report last year.

China views these actions as a continuation of politics rather than warfare, deliberately keeping them below the threshold of open conflict, the report added. This allows Beijing to secure economic resources in disputed territories, while limiting the ability of other countries to do the same.

Some recent moves from Washington have been reassuring. On Wednesday last week, the US deployed two warships to Scarborough Shoal (Huangyan Island, 黃岩島), the site of the collision, in an apparent show of support.

Beijing said it had expelled one of the US ships that entered its territorial waters, while Washington defended the operation as legal under international law.

Such freedom-of-navigation operations must continue in the face of China’s expanding claims, even at the risk of further angering Beijing. Equally important is consistently raising awareness about its destabilizing actions, challenging the narrative of ownership.

These incidents cannot be shrugged off as routine. Left unchecked, the dangers of a miscalculation would only grow in China’s high-seas game of chicken. One wrong move could ignite a much wider crisis.

Karishma Vaswani is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asia politics with a special focus on China. Previously, she was the BBC’s lead Asia presenter, and worked for the BBC across Asia and South Asia for two decades. This column reflects the personal views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Donald Trump’s return to the White House has offered Taiwan a paradoxical mix of reassurance and risk. Trump’s visceral hostility toward China could reinforce deterrence in the Taiwan Strait. Yet his disdain for alliances and penchant for transactional bargaining threaten to erode what Taiwan needs most: a reliable US commitment. Taiwan’s security depends less on US power than on US reliability, but Trump is undermining the latter. Deterrence without credibility is a hollow shield. Trump’s China policy in his second term has oscillated wildly between confrontation and conciliation. One day, he threatens Beijing with “massive” tariffs and calls China America’s “greatest geopolitical

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairwoman Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) made the astonishing assertion during an interview with Germany’s Deutsche Welle, published on Friday last week, that Russian President Vladimir Putin is not a dictator. She also essentially absolved Putin of blame for initiating the war in Ukraine. Commentators have since listed the reasons that Cheng’s assertion was not only absurd, but bordered on dangerous. Her claim is certainly absurd to the extent that there is no need to discuss the substance of it: It would be far more useful to assess what drove her to make the point and stick so

The central bank has launched a redesign of the New Taiwan dollar banknotes, prompting questions from Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) legislators — “Are we not promoting digital payments? Why spend NT$5 billion on a redesign?” Many assume that cash will disappear in the digital age, but they forget that it represents the ultimate trust in the system. Banknotes do not become obsolete, they do not crash, they cannot be frozen and they leave no record of transactions. They remain the cleanest means of exchange in a free society. In a fully digitized world, every purchase, donation and action leaves behind data.

Yesterday, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), once the dominant political party in Taiwan and the historic bearer of Chinese republicanism, officially crowned Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) as its chairwoman. A former advocate for Taiwanese independence turned Beijing-leaning firebrand, Cheng represents the KMT’s latest metamorphosis — not toward modernity, moderation or vision, but toward denial, distortion and decline. In an interview with Deutsche Welle that has now gone viral, Cheng declared with an unsettling confidence that Russian President Vladimir Putin is “not a dictator,” but rather a “democratically elected leader.” She went on to lecture the German journalist that Russia had been “democratized