As the sun sets on the third UN Ocean Conference in Nice, France, there is much to celebrate, but also much unfinished business for the world to address at the UN Climate Change Conference (COP30) in Belem, Brazil, later this year.

Against a backdrop of global uncertainty and questions about whether multilateral processes can still deliver, the nations represented in Nice were largely united on the need for a more ambitious response to the challenges facing our oceans, but this was only the first leg of the journey. To protect this life-preserving global commons in time, much more must be done ahead of COP30.

Among the outcomes to celebrate, the High Seas Treaty has made remarkable progress. With 19 nations ratifying it in Nice, and another dozen committing to do so, we are now on course to make this landmark global agreement operational by the start of next year, enabling the creation of marine protected areas on the high seas. That would plug an enormous hole in ocean governance.

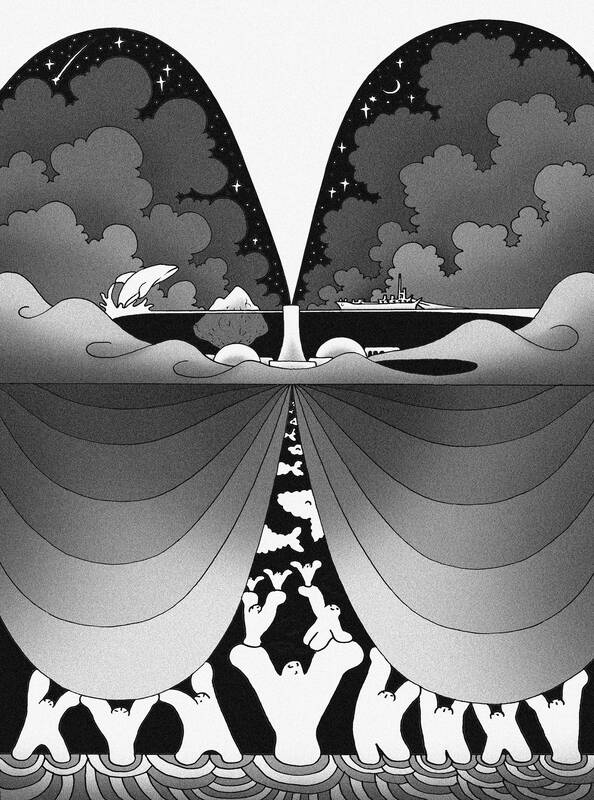

Illustration: Mountain People

Achieving the goal of protecting at least 30 percent of the world’s oceans by 2030 is not possible without setting aside large areas of the vast high seas — an area representing two-thirds of the oceans and half our planet’s surface. Establishing effective marine protection is especially urgent in polar regions, which are on the front line of the climate crisis. The situation in the Southern Ocean is dire, demanding immediate action to advance long-stalled proposals for marine protected areas. Such protections would both safeguard the ocean’s ability to help mitigate climate change (by absorbing carbon) and increase marine species’ resilience against warming temperatures (such as by removing pressures from overfishing).

In Nice, several nations also announced significant new marine protections in their national waters, with French Polynesia announcing what, at nearly 5 million square kilometers, would be the world’s largest network of protected areas, and the conference delivered welcome progress toward combating plastic pollution and restricting the most harmful fishing practices. However, none of these milestones should be mistaken as a turning of the tide for ocean protection. Rather, each must be part of a broader shift — a rising tide of higher ambitions that still has further to go.

Consider what remains to be done.

First, we are still falling woefully short in designating and enforcing marine protection. Even after Nice, only 10 percent of oceans are now protected in some fashion. That is a long way from the 30 percent we need to protect by the end of the decade. Worse, many protected areas are protected in name only. For example, many hoped that an environmental champion such as France would have announced a strict ban on bottom trawling in its protected areas. Still, there is time for more nations to set an example, including at COP30.

Second, dollars still count. There remains a big gap between what has been pledged and what has been delivered. Globally, only US$1.2 billion annually is going toward ocean protection, less than 10 percent of what is needed, even when studies show that protecting 30 percent of oceans by 2030 could unlock US$85 billion annually by 2050. In fact, redirecting the money allocated to harmful fishing subsidies in just 10 nations would plug the financing gap for ocean protection. Government spending must rehabilitate, not debilitate, this critical resource.

Third, the silence in Nice on ending our fossil-fuel addiction was deafening. Although the world committed two years ago, at COP28 in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, to “transition away” from fossil fuels, this issue seems to be relitigated at every multilateral convening. With the climate crisis providing an existential threat to all life on our blue planet, new unmitigated offshore oil and gas development is antithetical to all our stated goals.

Still, one bright spot was the Blue NDC Challenge — launched by Brazil and France, and supported by eight inaugural nations — which is pushing for ocean-based measures to be included in national climate plans.

The Nice conference must become a springboard for greater ocean action in Belem. COP30 is the ideal platform to announce new marine protections and financing for conservation efforts in developing nations, and for resilience-building in vulnerable island and coastal countries.

As the COP30 president and a coastal country itself, Brazil has the opportunity to use the momentum generated in Nice to integrate the world’s response to our connected climate and ocean crises. We have a choice. We can be the generation that turned ambition into action, or we can let our most important global commons collapse irretrievably. The oceans cannot wait. COP30 must deliver.

John F. Kerry is a former US secretary of state and special presidential envoy for climate.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

Father’s Day, as celebrated around the world, has its roots in the early 20th century US. In 1910, the state of Washington marked the world’s first official Father’s Day. Later, in 1972, then-US president Richard Nixon signed a proclamation establishing the third Sunday of June as a national holiday honoring fathers. Many countries have since followed suit, adopting the same date. In Taiwan, the celebration takes a different form — both in timing and meaning. Taiwan’s Father’s Day falls on Aug. 8, a date chosen not for historical events, but for the beauty of language. In Mandarin, “eight eight” is pronounced

In a recent essay, “How Taiwan Lost Trump,” a former adviser to US President Donald Trump, Christian Whiton, accuses Taiwan of diplomatic incompetence — claiming Taipei failed to reach out to Trump, botched trade negotiations and mishandled its defense posture. Whiton’s narrative overlooks a fundamental truth: Taiwan was never in a position to “win” Trump’s favor in the first place. The playing field was asymmetrical from the outset, dominated by a transactional US president on one side and the looming threat of Chinese coercion on the other. From the outset of his second term, which began in January, Trump reaffirmed his

US President Donald Trump’s alleged request that Taiwanese President William Lai (賴清德) not stop in New York while traveling to three of Taiwan’s diplomatic allies, after his administration also rescheduled a visit to Washington by the minister of national defense, sets an unwise precedent and risks locking the US into a trajectory of either direct conflict with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) or capitulation to it over Taiwan. Taiwanese authorities have said that no plans to request a stopover in the US had been submitted to Washington, but Trump shared a direct call with Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平)

It is difficult to think of an issue that has monopolized political commentary as intensely as the recall movement and the autopsy of the July 26 failures. These commentaries have come from diverse sources within Taiwan and abroad, from local Taiwanese members of the public and academics, foreign academics resident in Taiwan, and overseas Taiwanese working in US universities. There is a lack of consensus that Taiwan’s democracy is either dying in ashes or has become a phoenix rising from the ashes, nurtured into existence by civic groups and rational voters. There are narratives of extreme polarization and an alarming