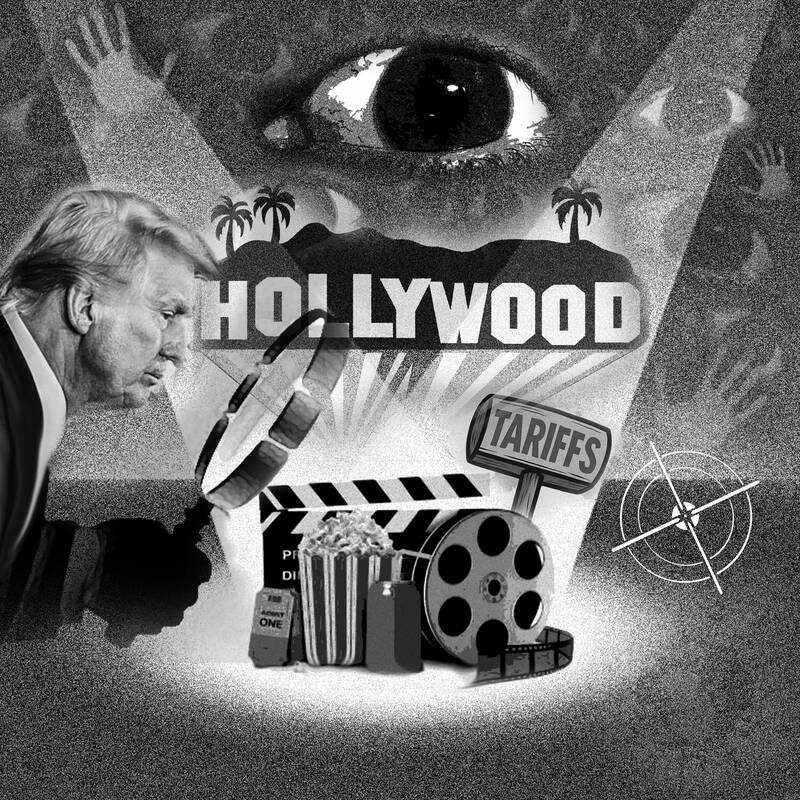

US President Donald Trump let the world know last weekend that movies have become another one of his tariff targets.

“The Movie Industry in America is DYING a very fast death,” he wrote on social media. “Other Countries are offering all sorts of incentives to draw our filmmakers and studios away from the United States … This is a concerted effort by other Nations and, therefore, a National Security threat. It is, in addition to everything else, messaging and propaganda! ... WE WANT MOVIES MADE IN AMERICA, AGAIN!”

To get the “credit where due” piece of this out of the way: As with the administration’s overall tariff policy, there is in fact a genuine economic issue to consider here. Big-budget studio blockbusters are taking advantage of tax breaks, cheaper labor and other incentives to shoot in London, New Zealand and Canada (among others). Mid and low-budget genre films are frequently shot in eastern European countries such as Romania and Bulgaria for the same reasons. Animation and post-production work (such as editing and special effects) are also typically farmed out overseas.

Illustration: Kevin Sheu

However, a broad and sweeping “solution” like this amounts to using a chainsaw for a job that requires a scalpel — a familiar theme within this administration.

How would one even impose a tariff on “movies”? This is an art form. It is not like a car or a television, where you purchase the individual parts and assemble them into a product that comes over in a shipping container. Movies are comprised of ideas brought to life by the labor and talent of skilled professionals, and more often than not these days, they are digitally transmitted — not contained in a physical form.

Does Trump want to tariff ticket prices? Does he propose making Blu-rays for foreign films twice as expensive? What about streaming services, which typically fill out their catalogs with international programming?

More importantly, as economics professor Justin Wolfers noted on Bluesky, the US exports far more films and television shows than it imports. Most Hollywood blockbusters at least match, if not exceed, their domestic grosses with foreign ticket sales. So, if typically lucrative markets like China, the UK, Japan and Australia choose to impose retaliatory tariffs on American movies, well, that would be the very definition of, to borrow Trump’s words, a “very fast death” for the “movie industry in America.”

China, for its part, threatened to do just that nearly a month ago when Trump was not even talking about movies yet.

However, we are not just talking about a financial loss. Art, in whatever medium, can offer different perspectives and unite communities. Movies are particularly adept at exploring complex themes in a relatively tight time frame; they are, and always have been, a universal language for the exchange of our individual stories, histories and ideas.

The US has benefited greatly from this trade— so much so that Hollywood is considered one of the country’s soft powers. And it is not a one-way street. Foreign films allow more members of our melting pot to see themselves onscreen; they also inspire domestic filmmakers, and contribute to the growth of the art. There are other, less high-minded benefits to boot. The South Korean hit Parasite, for example, grossed US$50 million-plus in the US, with moviegoers not only spending money on tickets, but popcorn, candy and drinks, boosting theaters’ bottom lines.

The logistics of a tariff on movies, it seems, have not been well thought out.

As if on schedule, the White House has already issued a statement all but walking back the president’s jeremiad.

However, the message cannot be walked back. As with the administration’s aggressive rollbacks of diversity, equity and inclusion policies, and targeted whitewashing of American history, the announcement of this movie tariff is indicative of the MAGA movement’s ongoing effort to reshape American life and culture. What is left behind is a cultural vacuum, which prompts a simple question: What will fill it? Trump, of course, has ideas.

I am reminded of 2019 when he devoted time at one of his re-election rallies to address the then-recent Oscar sweep Parasite.

“The winner is ... a movie from South Korea! What the hell was that all about?” he said. “We got enough problems with South Korea with trade. On top of that, they give them best movie of the year? Was it good? I don’t know. Let’s get Gone With the Wind. Can we get Gone With the Wind back, please?”

The most chilling words in his social post last weekend, at least for students of history, are the ones that, at first, read as a sidebar: his contention that, in addition to the economic impact of overseas production, “other Nations” are using movies to carry their own nefarious “messaging and propaganda.”

This was the same accusation lobbed at left-leaning screenwriters and directors during the dark days of the Hollywood blacklist and the investigations of the US House of Representatives Committee on Un-American Activities. During that time, creativity was stifled and industry professionals were locked out of jobs and opportunities.

There is little reason to believe that the Trump administration — in the name of its all-purpose interest in “national security” — will not follow the same path.

Some might think that is hyperbole or paranoia.

Perhaps.

However, if we have learned one thing over the past decade, it is that we underestimate Trump and those he has placed in power, and the extremity of their views and their goals, at our own peril.

Jason Bailey is a film critic, author and historian whose work has appeared in the New York Times, Vulture, the Playlist, Slate and Rolling Stone. This column reflects the personal views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Taiwan stands at the epicenter of a seismic shift that will determine the Indo-Pacific’s future security architecture. Whether deterrence prevails or collapses will reverberate far beyond the Taiwan Strait, fundamentally reshaping global power dynamics. The stakes could not be higher. Today, Taipei confronts an unprecedented convergence of threats from an increasingly muscular China that has intensified its multidimensional pressure campaign. Beijing’s strategy is comprehensive: military intimidation, diplomatic isolation, economic coercion, and sophisticated influence operations designed to fracture Taiwan’s democratic society from within. This challenge is magnified by Taiwan’s internal political divisions, which extend to fundamental questions about the island’s identity and future

Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) Chairman Huang Kuo-chang (黃國昌) is expected to be summoned by the Taipei City Police Department after a rally in Taipei on Saturday last week resulted in injuries to eight police officers. The Ministry of the Interior on Sunday said that police had collected evidence of obstruction of public officials and coercion by an estimated 1,000 “disorderly” demonstrators. The rally — led by Huang to mark one year since a raid by Taipei prosecutors on then-TPP chairman and former Taipei mayor Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) — might have contravened the Assembly and Parade Act (集會遊行法), as the organizers had

Minister of Foreign Affairs Lin Chia-lung (林佳龍) last week made a rare visit to the Philippines, which not only deepened bilateral economic ties, but also signaled a diplomatic breakthrough in the face of growing tensions with China. Lin’s trip marks the second-known visit by a Taiwanese foreign minister since Manila and Beijing established diplomatic ties in 1975; then-minister Chang Hsiao-yen (章孝嚴) took a “vacation” in the Philippines in 1997. As Taiwan is one of the Philippines’ top 10 economic partners, Lin visited Manila and other cities to promote the Taiwan-Philippines Economic Corridor, with an eye to connecting it with the Luzon

The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) has postponed its chairperson candidate registration for two weeks, and so far, nine people have announced their intention to run for chairperson, the most on record, with more expected to announce their campaign in the final days. On the evening of Aug. 23, shortly after seven KMT lawmakers survived recall votes, KMT Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) announced he would step down and urged Taichung Mayor Lu Shiow-yen (盧秀燕) to step in and lead the party back to power. Lu immediately ruled herself out the following day, leaving the subject in question. In the days that followed, several