In 1968, protests against the Vietnam War swept through US college campuses and, in some cases, turned violent. At Columbia University, student protesters were angry about several issues, as James Simon Kunen chronicled in The Strawberry Statement, a series that first ran in New York Magazine and was later published as a book.

The protesting students opposed Columbia’s ties with the Institute for Defense Analyses, a think tank researching war strategy, and the university’s plans to build a gym in Harlem’s Morningside Park. After students shut down the university and occupied several buildings in April 1968, the New York Police Department (NYPD) forcibly removed them.

However, student revolts and strikes, and the resulting campus violence, were not confined to the US. In March 1968, the commencement at the University of Tokyo, Japan’s most selective university, was canceled due to protests staged by medical students and interns.

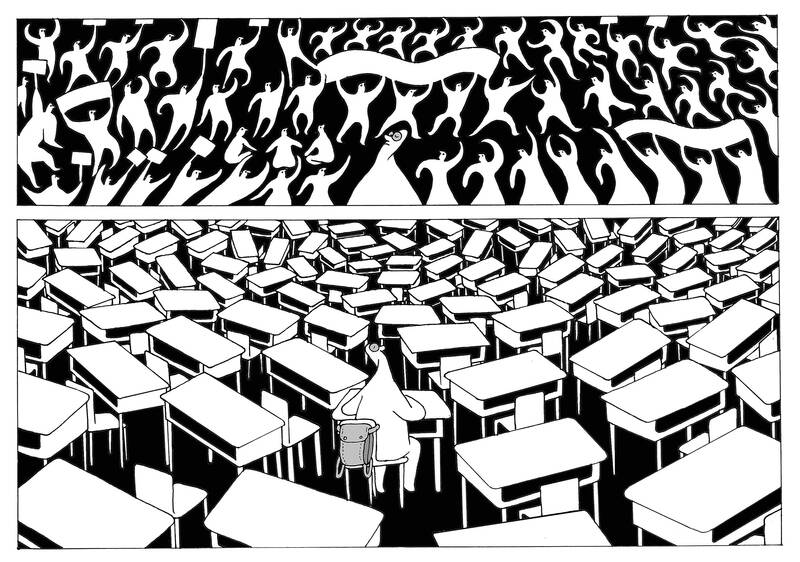

Illustration: Mountain People

Turmoil soon spread to the rest of the university, attracting radical leftists from other colleges. About 600 students — many of whom did not attend the University of Tokyo — eventually occupied Yasuda Auditorium, a campus symbol that housed the president’s office, for months.

By the end of 1968, the Japanese government threatened to cancel the University of Tokyo’s entrance exam, scheduled for the following March, if the situation was not normalized by mid-January. On Jan. 18 to 19, 1969, 8,500 police officers fought for about 48 hours to retake Yasuda Auditorium in a nationally televised battle.

At the time, I was studying for the University of Tokyo’s entrance exam and, like many high-school seniors across Japan, was deeply disappointed and confused when the Ministry of Education held firm to its decision.

The admission freeze had a cascading effect, forcing an entire cohort of seniors to aim lower and suffer the consequences, as graduating from a top university has been shown in some instances to influence promotion and pay progression. Ironically, some of the student radicals later embraced conservatism, using their elite credentials to land government and corporate jobs.

The experience taught me several lessons — above all, that the world is unfair. It also exposed fundamental flaws in university governance, whereby a vocal minority can override the silent majority. Neither the Japanese government, the University of Tokyo nor the protesters seemed to consider the damage wrought on us high-school seniors.

Since then, I have had little sympathy for protesters who disrupt the lives of bystanders, no matter how noble their cause. The pro-Palestinian protests at Columbia, where I am a professor, have done nothing to change my view. Instead, the experience has made me more appreciative of university administrators who can take decisive action to protect the silent majority.

Pressure began to build on April 17, when Columbia University president Minouche Shafik faced a grilling on Capitol Hill in Washington. Republican members of the House of Representatives Committee on Education and the Workforce called into question the university’s handling of pro-Palestinian protesters. However, Shafik emerged from the hearing relatively unscathed. For example, when asked: “Does calling for a genocide of Jews violate Columbia’s code of conduct?” — a question that tripped up the presidents of Harvard, MIT and the University of Pennsylvania at an earlier congressional hearing — Shafik simply said: “Yes.” That same day, pro-Palestinian protesters pitched tents on the south lawn of Columbia’s main campus.

On April 18, Shafik called in the NYPD to clear the tents, explaining that students had ignored the administration’s warning about occupying the lawn. I found this move to be sudden and a bit hasty, because the encampment was not disrupting the lives of others. Many of us on the faculty considered this a tactical error — inviting the police onto campus to remove students from the property forcibly or to arrest them is always a weighty decision that could invite a backlash. Unsurprisingly, the students returned with their tents.

At the start of the last week of instruction before final exams, the administration decided that classes would move online “to de-escalate the rancor and give us all a chance to consider next steps,” expressing concern that some students felt under threat and were afraid to come to campus. Offering online classes is an effective response to small-scale protests, and the ability to do so is one of the major differences between now and 1968, when students went on “strike” and refused to attend classes.

Even though the board of trustees professed its support for Shafik, the Columbia University senate, led by members who disagreed with her decision to summon the police, called for an investigation into the administration’s response. Shafik, the provost, and the cochairs of the board of trustees then announced that they were engaging in dialogue with the protesters and would not bring back the NYPD to dismantle the encampment.

However, after a few days, the administration set a deadline to clear the encampment and warned that it would initiate disciplinary procedures against students who did not comply. That night, pro-Palestinian protesters occupied Hamilton Hall — the first building that anti-war protesters took over in 1968. This represented a major escalation that breached several university rules.

Within 24 hours, the administration wisely asked the NYPD to retake Hamilton Hall and clear the encampment, resulting in nearly 110 arrests. Some students and faculty members later voiced concerns that police officers were allowed back on campus, though such swift action probably prevented protesters from occupying other buildings, including Low Library, where the president’s office is located, as their counterparts in 1968 had.

However, much of the damage had already been done. Columbia announced that all remaining final exams would be held remotely. Again, online teaching technology is useful in a crisis, but the timing and reason proved unfortunate. Switching to a remote final requires extra work and preparations for faculty and students, and the deadline for submitting grades was pushed back. The School of International and Public Affairs, where I teach, recognized the disruptiveness of these events and announced that students could switch to pass/fail for all courses this semester, even after the release of conventional grades.

However, in my view, the main question was whether Columbia would be able to hold commencement ceremonies on May 15. Unfortunately, on May 6, the administration announced its decision to cancel the university-wide ceremony, which would have been held in front of Low Library, and to hold, instead, smaller ceremonies for each of its 19 schools at various different locations, including the Baker Athletics Complex more than 100 blocks north of the main campus.

This decision has devastated college seniors — many of whom did not have a normal high-school graduation due to COVID-19 — and graduate students. Many of my students are upset, as are their parents, who are flying in from all over the world to watch their children graduate.

The pro-Palestinian demonstrations at Columbia, like the student protests at the University of Tokyo in 1968 to 1969, show how a small group of people can disrupt the lives of others in the community — whether through the cancelation of an entrance exam or a commencement ceremony. A righteous cause does not give students the right to act in a way that adversely affects their peers’ studies, careers and memories of university life. The resulting feelings of disappointment and frustration, if not intense anger, can last a lifetime.

Takatoshi Ito, a former Japanese deputy vice minister of finance, is a professor at the School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University and a senior professor at the National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies in Tokyo.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

The saga of Sarah Dzafce, the disgraced former Miss Finland, is far more significant than a mere beauty pageant controversy. It serves as a potent and painful contemporary lesson in global cultural ethics and the absolute necessity of racial respect. Her public career was instantly pulverized not by a lapse in judgement, but by a deliberate act of racial hostility, the flames of which swiftly encircled the globe. The offensive action was simple, yet profoundly provocative: a 15-second video in which Dzafce performed the infamous “slanted eyes” gesture — a crude, historically loaded caricature of East Asian features used in Western

Is a new foreign partner for Taiwan emerging in the Middle East? Last week, Taiwanese media reported that Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Francois Wu (吳志中) secretly visited Israel, a country with whom Taiwan has long shared unofficial relations but which has approached those relations cautiously. In the wake of China’s implicit but clear support for Hamas and Iran in the wake of the October 2023 assault on Israel, Jerusalem’s calculus may be changing. Both small countries facing literal existential threats, Israel and Taiwan have much to gain from closer ties. In his recent op-ed for the Washington Post, President William

A stabbing attack inside and near two busy Taipei MRT stations on Friday evening shocked the nation and made headlines in many foreign and local news media, as such indiscriminate attacks are rare in Taiwan. Four people died, including the 27-year-old suspect, and 11 people sustained injuries. At Taipei Main Station, the suspect threw smoke grenades near two exits and fatally stabbed one person who tried to stop him. He later made his way to Eslite Spectrum Nanxi department store near Zhongshan MRT Station, where he threw more smoke grenades and fatally stabbed a person on a scooter by the roadside.

Taiwan-India relations appear to have been put on the back burner this year, including on Taiwan’s side. Geopolitical pressures have compelled both countries to recalibrate their priorities, even as their core security challenges remain unchanged. However, what is striking is the visible decline in the attention India once received from Taiwan. The absence of the annual Diwali celebrations for the Indian community and the lack of a commemoration marking the 30-year anniversary of the representative offices, the India Taipei Association and the Taipei Economic and Cultural Center, speak volumes and raise serious questions about whether Taiwan still has a coherent India