The town of Joshimath might be nestled 1,800m above sea level in the Himalayas, but it is sinking fast. Early last month, large cracks split homes, hotels and roads, leaving the town’s future hanging in the balance.

Joshimath is a grim metaphor for India’s woefully unaccountable state.

The town is located in a seismically active zone of landslide debris and sediment layered over a weak assemblage of rocks. Such terrain naturally sinks and slides, but the problem is made worse by deforestation.

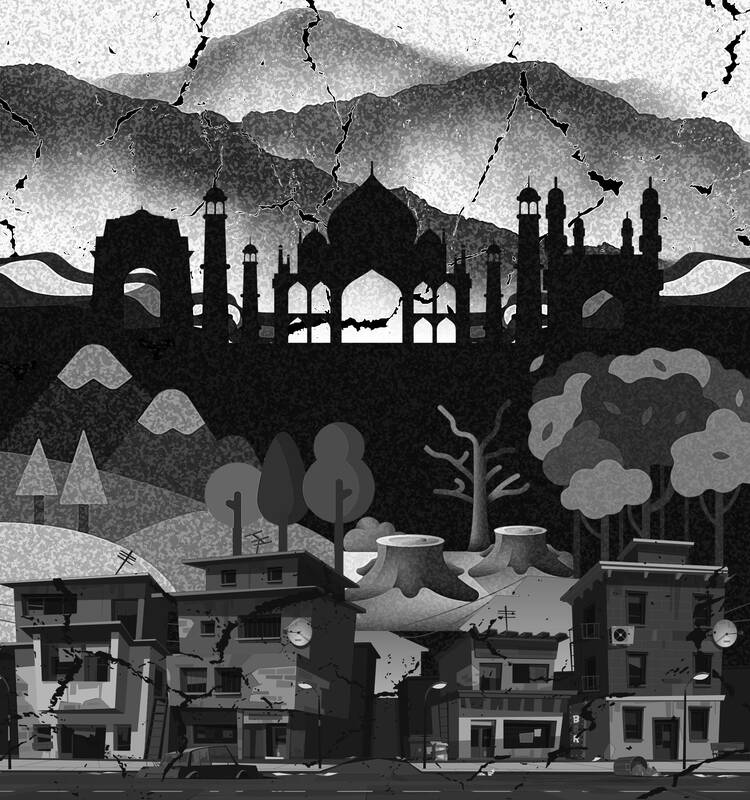

Illustration: Louise Ting

Moreover, because the Alaknanda River — a tributary of the Ganges — has eroded the northwestern toe of the slope on which Joshimath stands, the formation does not have a high load-bearing capacity, as has been known since the 1930s.

Cracks appeared in Joshimath’s roads in the 1970s. In 1976, a committee appointed by the government of Uttar Pradesh, of which Joshimath was then a part, reiterated the risk of subsidence (sinking) and advised that construction be undertaken only in areas determined to be stable. This official warning went unheeded, and local activists fought unsuccessfully to forestall unsafe construction.

The problem grew worse following the economic liberalization of the early 1990s, when the state endorsed and supported a form of unregulated capitalism, which often centered around lucrative construction contracts and featured a total disregard — even contempt — for the environment.

Joshimath’s current troubles began innocuously in 1993, when Auli, a neighboring town, began construction of a ski-resort ropeway. That was the opening salvo in a much broader construction program.

State authorities soon launched ambitious plans for hydroelectric dams to harness the energy from Himalayan runoff. The 400-megawatt Vishnuprayag plant became operational in 2006, and construction of the more controversial 520-megawatt Tapovan-Vishnugad dam began the same year.

To generate electricity from the project, a tunnel had to be built under the Joshimath hillslope, directly below the Auli ski resort. In 2009, a tunnel-boring machine punctured an aquifer in the mountain, depleting the groundwater on which Joshimath and other nearby towns depended. Sediment then filled the gaps left by the receding water, which some experts and activists believe added to the area’s subsidence tendency.

In June 2013, a disastrous flood killed more than 4,000 people in the area, leading to legal proceedings in which the Supreme Court expressed grave concerns over the “mushrooming” of dams in the region.

The court was aghast that the authorities had not scientifically assessed “the cumulative impact” of the dams and the associated blasting, tunneling, muck disposal, mining and deforestation. Under a court order, the government appointed an expert committee headed by environmental scientist and activist Ravi Chopra.

The Chopra Committee concluded that the Himalayan mountains, rivers and communities were in “a crisis” exacerbated by global warming. The government’s “rampant development” approach, the committee said, would cause more deforestation and biodiversity loss alongside “unpredictable glacial and paraglacial activities.”

Warning that this explosive combination would invite even greater disasters in the future, the committee proposed halting work on 23 dams.

When a second committee endorsed the Chopra Committee’s judgment, the government appointed a third committee that gave the go-ahead for more dams, and in July 2020, the authorities invited bids for the Helang-Marwari bypass road through a fragile landslide zone near the foot of the Joshimath hill. Construction of the bypass began two years later as part of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s ecologically damaging program to ease travel to the holy shrines in the Himalayas.

Disasters continued to take lives. In February 2021, another flood killed a few hundred people, mainly around Tapovan-Vishnugad and another dam site. The dams themselves were almost irreparably damaged, and activists called on the Uttarakhand High Court to halt dam construction. The court threw out the case, reprimanding the petitioners and fining them for wasting its time.

After unusually heavy rains in October 2021, the cracks in Joshimath reached a tipping point. Last month, the threat of collapsing structures had made large parts of the town uninhabitable. Hundreds of residents have been herded into shelters, and the government has halted the rehabilitation of the Tapovan-Vishnugad dam and construction of the Helang-Marwari bypass.

Yet with calamity looming, credible information has become hard to come by. National authorities recently ordered the Indian Space Research Organization to unpublish satellite images that reveal the pace at which Joshimath is sinking, and officials are now prohibited from speaking to the media about the matter.

Joshimath is hardly alone. Many other towns and roads throughout the Himalayan range are showing similar signs of stress. This should surprise no one. It is yet another symptom of Indian authorities’ criminal lack of accountability.

More tipping points loom as forests are being cleared; lakes, wetlands and natural water reservoirs are being built over; urban areas are contending with mountains of garbage; and rivers have been almost irreversibly polluted. Education, healthcare, the judicial system and city services work mainly for the privileged.

The practice of embellishing data, integral to the lack of accountability, extends to macroeconomic management. GDP growth jumped inexplicably after a data revision in 2015. In 2018, the government rejected its own survey when it showed that poverty had increased.

The Indian Ministry of Finance reported absurdly unrealistic unemployment figures, despite a jobs crisis. A census conducted each decade was due in 2021, but has been postponed until some unknown future date.

India’s elite, with its “see-no-evil” approach to economic discourse and policy, has blotted out Joshimath’s fate as an aberration of nature. Instead, world-class electronic-payment systems and technology-based startups have fed a global narrative of an imminent “Indian century.”

Make no mistake, though. Joshimath is a microcosm of the brazen unaccountability corroding Indian politics and society. It should be a reality check, not a footnote.

Ashoka Mody is a visiting professor of international economic policy at Princeton University, and previously worked for the World Bank and the IMF.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) were born under the sign of Gemini. Geminis are known for their intelligence, creativity, adaptability and flexibility. It is unlikely, then, that the trade conflict between the US and China would escalate into a catastrophic collision. It is more probable that both sides would seek a way to de-escalate, paving the way for a Trump-Xi summit that allows the global economy some breathing room. Practically speaking, China and the US have vulnerabilities, and a prolonged trade war would be damaging for both. In the US, the electoral system means that public opinion

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

They did it again. For the whole world to see: an image of a Taiwan flag crushed by an industrial press, and the horrifying warning that “it’s closer than you think.” All with the seal of authenticity that only a reputable international media outlet can give. The Economist turned what looks like a pastiche of a poster for a grim horror movie into a truth everyone can digest, accept, and use to support exactly the opinion China wants you to have: It is over and done, Taiwan is doomed. Four years after inaccurately naming Taiwan the most dangerous place on

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.