The Jan. 8 insurrection in Brazil’s capital was driven by a mix of factors. Participants’ delirium, passion, obstinacy and resentment, as well as their lack of education and political literacy, all played a part. While none of these factors justifies what happened, they can help us understand why it happened.

Like his role model, former US president Donald Trump, Brazil’s defeated president, Jair Bolsonaro, spun the narrative and created the conditions that led his followers to attack the seat of democratic governance. Well before losing his re-election bid in 2020, Trump had sowed doubts about the process, telling his supporters that fraud was likely. Bolsonaro followed suit, suggesting to his followers that if he lost last year’s election, they should conclude that it was rigged against him.

In both cases, the incumbents had prepared the ground for challenging the election results and fomenting outrage among their supporters. Once they had indeed lost, their followers had a clear target. While Trump ultimately mobilized his supporters to challenge the vote-certification process in the US Senate, where then-US vice president Mike Pence was the presiding officer, Bolsonaro focused on the issue of electronic voting machines, which are managed by the Superior Electoral Court (TSE) under the leadership of Brazilian Supreme Court Justice Alexandre de Moraes.

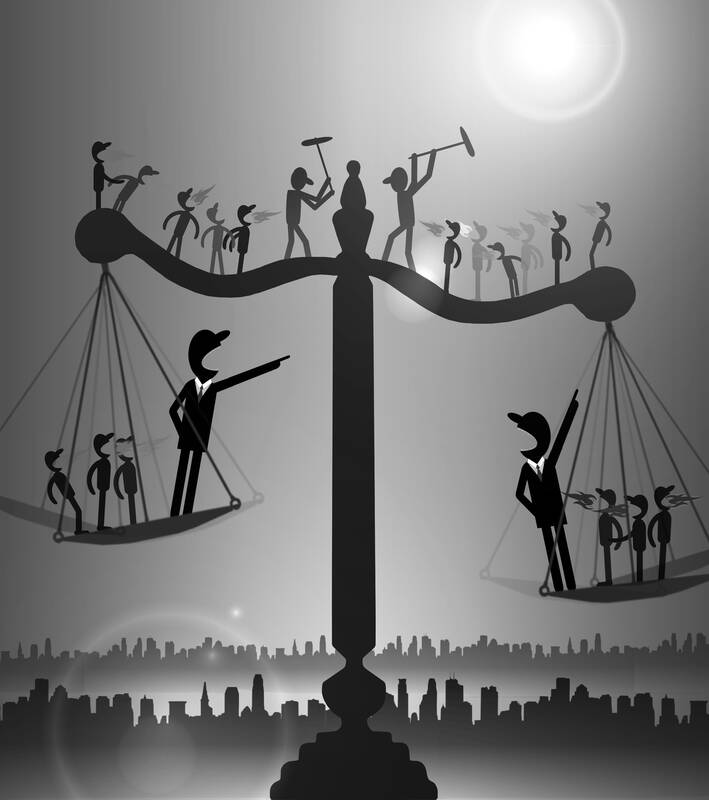

Illustration: Yusha

Since Bolsonaro had no concrete evidence to show that the electronic voting machines were vulnerable, he relied on the old maxim: “If you can’t convince them, confuse them.”

Many of his supporters already had their sights set on the TSE and De Moraes before the election. When Bolsonaro lost by only a narrow margin, even as his party performed well in the parliamentary election, the outcome seemed to corroborate his pre-election warnings about a looming communist coup (at least in the minds of his supporters).

Then, in the weeks following the election, false, distorted and exaggerated reports of voting irregularities were pumped out to Bolsonaro’s base through social media and other channels. Consumed by their dissatisfaction, many began to imagine that the result could still be reversed.

The first step was to deny the legitimacy of the newly elected government to justify suspending the usual rules. The events of Jan. 8 followed from the participants’ collective belief, which followed from the signals they had received from the former president and his allies, that violence and other lawless behavior were justified in confronting an even greater act of “illegality.”

While the full implications of Jan. 8 remain to be seen, we can already trace some of the immediate effects.

First, there is no denying that Bolsonarismo has shot itself in the foot. Even if the attacks on government buildings were spontaneous, they revealed a failure by now-suspended Federal District Governor Ibaneis Rocha, a Bolsonaro ally, to provide basic public security. If they were premeditated, they demonstrated an utter lack of maturity on the part of the planners.

Either way, Bolsonarismo’s image has been further tarnished. Any future peaceful demonstrations would be closely monitored, and more mainstream politicians who have previously aligned themselves with Bolsonaro presumably would not want to play a leading role in the official opposition.

Does Bolsonaro want to lead the opposition to Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva within Brazil’s political institutions, or does he want to lead an opposition movement in the streets?

He cannot have it both ways. To lead the formal opposition, Bolsonaro would have to condemn the insurrection unambiguously; but if he sides with the insurrectionists, he would strengthen Lula’s position regarding the Brazilian Congress. After all, Jan. 8 has brought together numerous government and opposition parliamentarians, and Lula would be looking to peel off support from center-right politicians who are questioning their ties to the former president.

Lula’s administration has promised a full investigation of the insurrection, including how it was funded and planned. Hundreds of participants have been arrested and would be prosecuted.

One pressing question is how the informal street opposition would respond now that De Moraes has temporarily removed Rocha. Could Bolsonaro allies leading other states meet a similar fate?

Much would depend on what Lula, Brazilian Minister of Defense Jose Mucio, and Brazilian Minister of Justice Flavio Dino do in the coming days. If they indulge their sense of outrage, they would risk strengthening the street opposition. They must choose whether to focus on the acts that can be prosecuted under the law. Targeting their enemies more broadly would merely perpetuate the pattern of polarization, further trivializing terms like “fascist” and “communist.”

However, if the government ensures accountability for criminal acts, it can reinforce the message that any attacks on democratic institutions, regardless of whether they come from the left or the right, would be met by swift enforcement of the rule of law.

More broadly, Jan. 8 shows what can happen when democracy is understood merely as a process, rather than as a core value. With Bolsonarismo having discredited itself, Brazil’s democracy is not immediately at risk.

However, that could change quickly unless Brazilians develop a more mature appreciation of how and why the procedures of democracy work.

Thiago de Aragao, executive director of public affairs at Arko Advice, is a senior research associate at the Center for Strategic & International Studies. Otaviano Canuto, a former vice president and executive director of the World Bank and executive director of the IMF, is a nonresident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and a senior fellow at the Policy Center for the New South.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

Congratulations to China’s working class — they have officially entered the “Livestock Feed 2.0” era. While others are still researching how to achieve healthy and balanced diets, China has already evolved to the point where it does not matter whether you are actually eating food, as long as you can swallow it. There is no need for cooking, chewing or making decisions — just tear open a package, add some hot water and in a short three minutes you have something that can keep you alive for at least another six hours. This is not science fiction — it is reality.

A foreign colleague of mine asked me recently, “What is a safe distance from potential People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Rocket Force’s (PLARF) Taiwan targets?” This article will answer this question and help people living in Taiwan have a deeper understanding of the threat. Why is it important to understand PLA/PLARF targeting strategy? According to RAND analysis, the PLA’s “systems destruction warfare” focuses on crippling an adversary’s operational system by targeting its networks, especially leadership, command and control (C2) nodes, sensors, and information hubs. Admiral Samuel Paparo, commander of US Indo-Pacific Command, noted in his 15 May 2025 Sedona Forum keynote speech that, as

In a world increasingly defined by unpredictability, two actors stand out as islands of stability: Europe and Taiwan. One, a sprawling union of democracies, but under immense pressure, grappling with a geopolitical reality it was not originally designed for. The other, a vibrant, resilient democracy thriving as a technological global leader, but living under a growing existential threat. In response to rising uncertainties, they are both seeking resilience and learning to better position themselves. It is now time they recognize each other not just as partners of convenience, but as strategic and indispensable lifelines. The US, long seen as the anchor

Kinmen County’s political geography is provocative in and of itself. A pair of islets running up abreast the Chinese mainland, just 20 minutes by ferry from the Chinese city of Xiamen, Kinmen remains under the Taiwanese government’s control, after China’s failed invasion attempt in 1949. The provocative nature of Kinmen’s existence, along with the Matsu Islands off the coast of China’s Fuzhou City, has led to no shortage of outrageous takes and analyses in foreign media either fearmongering of a Chinese invasion or using these accidents of history to somehow understand Taiwan. Every few months a foreign reporter goes to