The nationwide protests in Iran over women’s rights and abuses by the religious morality police have once again shined a light on the country’s ruling clerical class and the seemingly limitless powers of Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

The Islamic Republic has a two-tier government. The first tier, ostensibly representing the sovereignty of the people, includes a president who serves as the executive of a highly centralized state, a parliament charged with creating and debating laws, and a judiciary that vets and interprets those laws. The second tier, representing the sovereignty of God, consists of just one man: the supreme leader, or faqih.

The faqih has an absolute monopoly over state power. He appoints the head of the judiciary and can dismiss the president at will. He is the commander-in-chief of the army, and he can veto any law passed by parliament. The office is anachronistic and utterly unique, allowing for the institutionalization of clerical control over all aspects of government.

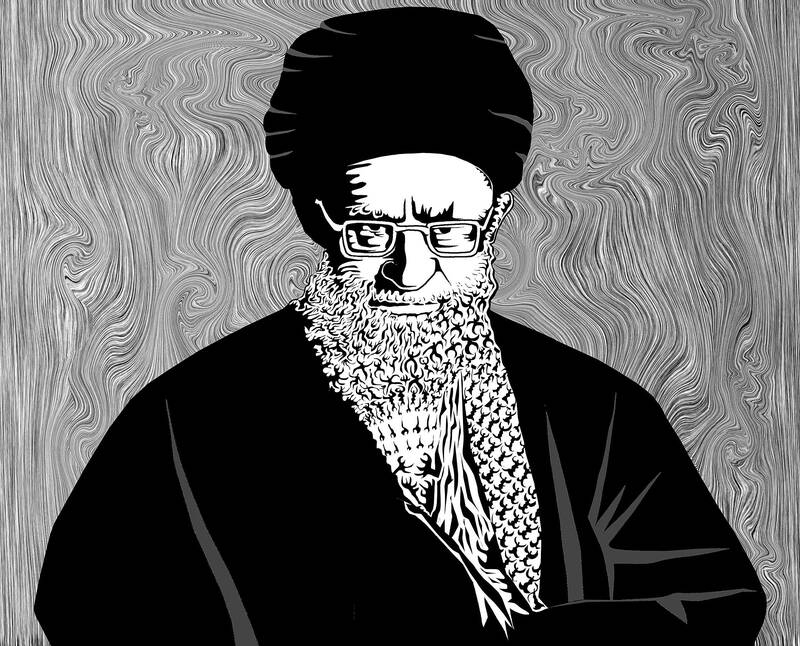

Illustration: Mountain People

It is also heretical. Far from being the foundation of Shia Islam, as Iran’s clerical regime claims, the concept of the faqih represents neither the historical consensus nor the current majority view of Shia political thought. It is a wholly made-up office, concocted by the man who first claimed the position for himself: former Iranian supreme leader ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.

Shiism, like Christianity, is messianic. Shia doctrine posits that the temporal world and all its imperfections would be swept away by the appearance of a figure known as the mahdi, who would one day rule over the Earth. Until then, all governments are temporary and illegitimate, as any exercise of direct political power would be considered a usurpation of the mahdi’s divine authority. Thus, for most of the past 1,400 years, Shia clergy have refused to interfere in governmental affairs, instead adopting a position of political quietism.

To be sure, Iran’s leading ayatollahs did fight alongside the country’s merchants and young intellectuals to create the first indigenous democratic movement in the Middle East. The Persian Constitutional Revolution of 1906, as it came to be known, resulted in the creation of a progressive constitution guaranteeing basic rights and freedoms for all Persians, an independent parliament (the Persian National Consultative Assembly), free elections and a clear separation of powers.

However, the revolution was short-lived. In 1921, a British-backed military coup established the Pahlavi dynasty in Iran. The constitution was discarded, parliament was defanged and the state reverted to dictatorship.

The Pahlavis brutally suppressed any political activity by the clergy. While a few prominent clerics participated in the country’s second revolution of the century, the so-called Iranian Nationalist Revolution of 1953, it was not until Iran’s third revolution, in 1979, that the clergy left the mosques and entered government.

That development owed everything to Khomeini’s unprecedented interpretation of the mahdi. Countering 14 centuries of Shia doctrine, he argued that, in the absence of the mahdi — the sole legitimate leader of an Islamic state — political power should rest in the hands of the mahdi’s representatives on Earth: the clergy. Put another way, rather than waiting for the mahdi to return at the end of time to create the perfect society, the clergy should be empowered to create the perfect society for him so that he would return at the end of time. Khomeini called this theory the valayat-e faqih, or “the guardianship of the jurist.”

This was an astounding assertion and a radical religious innovation in Shia Islam. Yet Khomeini went even further, saying that political authority should rest not with the whole of the clergy, but with a single “supreme” cleric.

He said that, as the deputy of the mahdi, the supreme cleric’s authority should be identical not just to the mahdi’s, but to that of the Prophet Mohammed himself.

“When a mujtahid [a qualified jurist] who is just and learned stands up for the establishment and organization of the government, he will enjoy all the rights in the affairs of the society that were enjoyed by the prophet,” Khomeini wrote in his political treatise Islamic Government.

No Muslim cleric had ever made so startling a proposal. The notion that any human being could have the same infallible, divine authority as the prophet contradicts centuries of Islamic theology.

The theory was so plainly heretical that it was immediately rejected by almost every other ayatollah in Iran, including Khomeini’s then-superiors, ayatollahs Hossein Kazemeyni Boroujerdi and Mohammad Kazem Shariatmadari, as well as nearly all grand ayatollahs in Najaf, Iraq — the religious center of Shia Islam.

What made Khomeini so alluring was his ability to couch his radical doctrine in the populist rhetoric of the time. Once his colleagues had been intimidated into silence and Iran’s pious masses had been stirred to action, Khomeini was free to seize control of the post-revolutionary government.

Before most Iranians knew what they had accepted, he had injected his interpretation of the mahdi into the political realm, transforming Iran into the Islamic Republic and proclaiming himself the country’s first faqih: the supreme temporal and religious authority.

In 1989, Khomeini died and the office of faqih passed to his hand-picked successor, Khamenei, with little clerical or popular resistance.

Even though the faqih was supposed to be Iran’s most learned religious authority, Khamenei was little more than a mid-level cleric — not even an ayatollah — with thin credentials. Nevertheless, he was given the office largely because practically every other qualified religious authority in Iran — including Khomeini’s first choice as successor, then-grand ayatollah Ali Montazeri — had decried the doctrine of the faqih as anathema to Islam.

Now 83 and in ill health, Khamenei is widely believed to be grooming his eldest son, Mojtaba Khamenei — a cleric of even lower rank than he was when selected — to succeed him as the next supreme leader.

That would strip away any last remnant of religious legitimacy the office still maintains, exposing the faqih for what it is: a synonym for Iranian shah.

Should that happen, the protests that would follow could dwarf the uprisings we are seeing today.

One of the most frequent chants heard on the streets during the current protests has been: “Mojtaba, we’ll see you die before becoming leader.”

Reza Aslan, an Emmy and Peabody Award-nominated producer, is a professor at the University of California, Riverside.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

Congratulations to China’s working class — they have officially entered the “Livestock Feed 2.0” era. While others are still researching how to achieve healthy and balanced diets, China has already evolved to the point where it does not matter whether you are actually eating food, as long as you can swallow it. There is no need for cooking, chewing or making decisions — just tear open a package, add some hot water and in a short three minutes you have something that can keep you alive for at least another six hours. This is not science fiction — it is reality.

A foreign colleague of mine asked me recently, “What is a safe distance from potential People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Rocket Force’s (PLARF) Taiwan targets?” This article will answer this question and help people living in Taiwan have a deeper understanding of the threat. Why is it important to understand PLA/PLARF targeting strategy? According to RAND analysis, the PLA’s “systems destruction warfare” focuses on crippling an adversary’s operational system by targeting its networks, especially leadership, command and control (C2) nodes, sensors, and information hubs. Admiral Samuel Paparo, commander of US Indo-Pacific Command, noted in his 15 May 2025 Sedona Forum keynote speech that, as

In a world increasingly defined by unpredictability, two actors stand out as islands of stability: Europe and Taiwan. One, a sprawling union of democracies, but under immense pressure, grappling with a geopolitical reality it was not originally designed for. The other, a vibrant, resilient democracy thriving as a technological global leader, but living under a growing existential threat. In response to rising uncertainties, they are both seeking resilience and learning to better position themselves. It is now time they recognize each other not just as partners of convenience, but as strategic and indispensable lifelines. The US, long seen as the anchor

Kinmen County’s political geography is provocative in and of itself. A pair of islets running up abreast the Chinese mainland, just 20 minutes by ferry from the Chinese city of Xiamen, Kinmen remains under the Taiwanese government’s control, after China’s failed invasion attempt in 1949. The provocative nature of Kinmen’s existence, along with the Matsu Islands off the coast of China’s Fuzhou City, has led to no shortage of outrageous takes and analyses in foreign media either fearmongering of a Chinese invasion or using these accidents of history to somehow understand Taiwan. Every few months a foreign reporter goes to