Power-hungry, fossil fuel dependent Japan has successfully tested a system that could provide a constant, steady form of renewable energy, regardless of the wind or the sun.

For more than a decade, Japanese heavy machinery maker IHI has been developing a subsea turbine that harnesses the energy in deep ocean currents, and converts it into a steady and reliable source of electricity. The giant machine resembles an airplane, with two counterrotating turbine fans in place of jets and a central “fuselage” housing a buoyancy adjustment system.

Called “Kairyu,” the 330 tonne prototype is designed to be anchored to the sea floor at a depth of 30m to 50m.

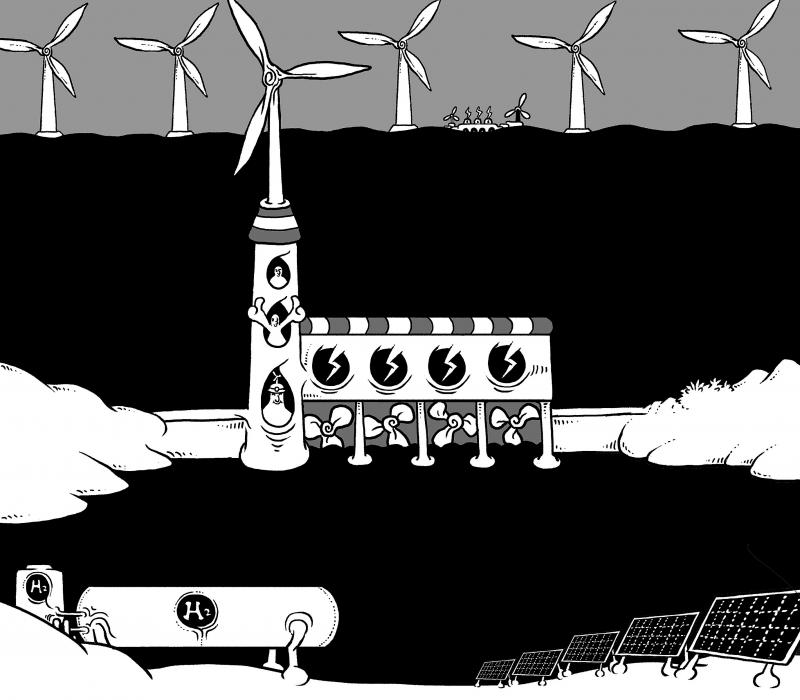

Illustration: Mountain People

In commercial production, the plan is to site the turbines in the Kuroshio Current, one of the world’s strongest, which runs along Japan’s eastern coast, and transmit the power via seabed cables.

“Ocean currents have an advantage in terms of their accessibility in Japan,” said Ken Takagi, a professor of ocean technology policy at the University of Tokyo Graduate School of Frontier Sciences. “Wind power is more geographically suited to Europe, which is exposed to predominant westerly winds and is located at higher latitudes.”

The Japanese New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO) estimates that the Kuroshio Current could potentially generate as much as 200 gigawatts — about 60 percent of Japan’s present generating capacity.

Like other nations, the lion’s share of investment in renewables has gone into wind and solar, especially after the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant disaster curbed Japan’s appetite for atomic energy.

The world’s third-largest generator of solar power, Japan is investing heavily in offshore wind, but harnessing ocean currents could provide the reliable baseline power needed to reduce the need for energy storage or fossil fuels.

The advantage of ocean currents is their stability. They flow with little fluctuation in speed and direction, giving them a capacity factor — a measure of how often the system is generating energy — of 50 to 70 percent, compared with about 27 percent for onshore wind and 15 percent for solar.

In February, IHI completed a three-year demonstration study of the technology with NEDO. Its team tested the system in the waters near the Tokara Islands in southwestern Japan by hanging Kairyu from a vessel and sending power back to the ship. It first drove the ship to artificially generate a current and then suspended the turbines in the Kuroshio.

The tests proved that the prototype could generate the expected 100 kilowatts of stable power, and the company now plans to scale up to a full 2 megawatt system that could be in commercial operation in the next decade or later.

Like other advanced maritime nations, Japan is exploring various ways of harnessing energy from the sea, including tidal and wave power, as well as ocean thermal energy conversion (OTEC), which exploits the difference in temperature between the surface and the deep ocean.

Mitsui OSK Lines has invested in UK-based Bombora Wave Power to explore the potential for the technology in Japan and Europe. The company is also investing in OTEC and in April began operating a 100 kilowatt demonstration facility in Okinawa, Japan, said Yasuo Suzuki, general manager of OSK’s marketing division.

Kyushu Electric’s renewable unit Kyuden Mirai Energy this year begins a ¥650 million (US$5.02 million) feasibility test to produce 1 megawatt of tidal power near Japan’s Goto Islands in the East China Sea.

The Japanese government this month also proposed changes to offshore wind auctions that could speed up development.

Among marine energy technologies, the one advancing fastest toward cost-effectiveness is tidal stream, where “the technology has advanced quite a long way and it definitely works,” said Angus McCrone, a former BloombergNEF chief editor and marine energy analyst.

Orbital Marine Power is one of several companies constructing tidal systems near Scotland’s Orkney Islands, location of the European Marine Energy Centre.

Others include SIMEC Atlantis Energy’s MeyGen array and Aquantis, founded by US wind pioneer James Dehlsen, which reportedly plans to start testing a tidal system off California next year.

While tidal flows do not run 24 hours, they tend to be stronger than deep ocean currents. The Kuroshio Current flows at about 1.5 meters per second, or less than half the speed of some tidal systems.

“The biggest issue for ocean current turbines is whether they could produce a device that would generate power economically out of currents that are not particularly strong,” McCrone said.

Ocean Energy Systems, an intergovernmental collaboration established by the International Energy Agency, sees the potential to deploy more than 300 gigawatts of ocean energy globally by 2050.

However, the potential for ocean energy is location dependent, taking into account the strength of currents, access to grids or markets, maintenance costs, shipping, marine life and other factors.

In Japan, wave energy is moderate and unstable through the year, while areas with strong tidal currents tend to have heavy shipping traffic, Takagi said.

OTEC is better suited to tropical regions where the temperature gradient is bigger.

One of the advantages of the deep ocean current is that it does not restrict navigation of ships, IHI said.

However, the Japanese company has a long way to go. Compared with onshore facilities, it is much more complicated to install a system underwater.

“Unlike Europe, which has a long history of the North Sea oil exploration, Japan has had little experience with offshore construction,” Takagi said.

There are major engineering challenges to build a system robust enough to withstand the hostile conditions of a deep ocean current and to reduce maintenance costs.

“Japan isn’t blessed with a lot of alternative energy sources,” he said. “People may say that this is just a dream, but we need to try everything to achieve zero carbon.”

With the cost of wind and solar power, and battery storage declining, IHI would also need to demonstrate that overall project costs for ocean current power are competitive.

IHI aims to generate power at ¥20 per kilowatt-hour from large-scale deployment.

That compares with about ¥17 for solar in the country and about ¥12 to ¥16 for offshore wind.

IHI also said it conducted an environmental assessment before it launched the project, and would use the test results to examine effects on the marine environment and fishing industry.

If successful at scale, deep ocean currents could add a vital part in providing green baseline power in the global effort to phase out fossil fuels.

IHI’s work could help Japan’s engineering take a leading role with government support, McCrone said.

IHI has to make a convincing argument that “Japan could benefit from being a technology leader in this area,” he said.

After more than a year of review, the National Security Bureau on Monday said it has completed a sweeping declassification of political archives from the Martial Law period, transferring the full collection to the National Archives Administration under the National Development Council. The move marks another significant step in Taiwan’s long journey toward transitional justice. The newly opened files span the architecture of authoritarian control: internal security and loyalty investigations, intelligence and counterintelligence operations, exit and entry controls, overseas surveillance of Taiwan independence activists, and case materials related to sedition and rebellion charges. For academics of Taiwan’s White Terror era —

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has long been expansionist and contemptuous of international law. Under Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平), the CCP regime has become more despotic, coercive and punitive. As part of its strategy to annex Taiwan, Beijing has sought to erase the island democracy’s international identity by bribing countries to sever diplomatic ties with Taipei. One by one, China has peeled away Taiwan’s remaining diplomatic partners, leaving just 12 countries (mostly small developing states) and the Vatican recognizing Taiwan as a sovereign nation. Taiwan’s formal international space has shrunk dramatically. Yet even as Beijing has scored diplomatic successes, its overreach

On Feb. 7, the New York Times ran a column by Nicholas Kristof (“What if the valedictorians were America’s cool kids?”) that blindly and lavishly praised education in Taiwan and in Asia more broadly. We are used to this kind of Orientalist admiration for what is, at the end of the day, paradoxically very Anglo-centered. They could have praised Europeans for valuing education, too, but one rarely sees an American praising Europe, right? It immediately made me think of something I have observed. If Taiwanese education looks so wonderful through the eyes of the archetypal expat, gazing from an ivory tower, how

China has apparently emerged as one of the clearest and most predictable beneficiaries of US President Donald Trump’s “America First” and “Make America Great Again” approach. Many countries are scrambling to defend their interests and reputation regarding an increasingly unpredictable and self-seeking US. There is a growing consensus among foreign policy pundits that the world has already entered the beginning of the end of Pax Americana, the US-led international order. Consequently, a number of countries are reversing their foreign policy preferences. The result has been an accelerating turn toward China as an alternative economic partner, with Beijing hosting Western leaders, albeit