China’s mass detention of Uighur Muslims — the largest of a religio-ethnic group since World War II — is not the inevitable or predictable outcome of Chinese communist policies toward ethnic minorities. I have spent the past 20 years studying ethnicity in China and, when viewing the present situation in Xinjiang through the prism of history, one thing becomes clear: This is not what was “supposed” to happen.

In the early 1950s the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) was holding on to revolutionary victory by its fingernails. The postwar economy was in a shambles, and the outbreak of the Korean War brought a nuclear hegemon to its doorstep in the form of the US. Not the moment most regimes would choose to enlarge their to-do lists.

However, the CCP did, committing to officially recognizing more minority peoples than any other Chinese regime in history.

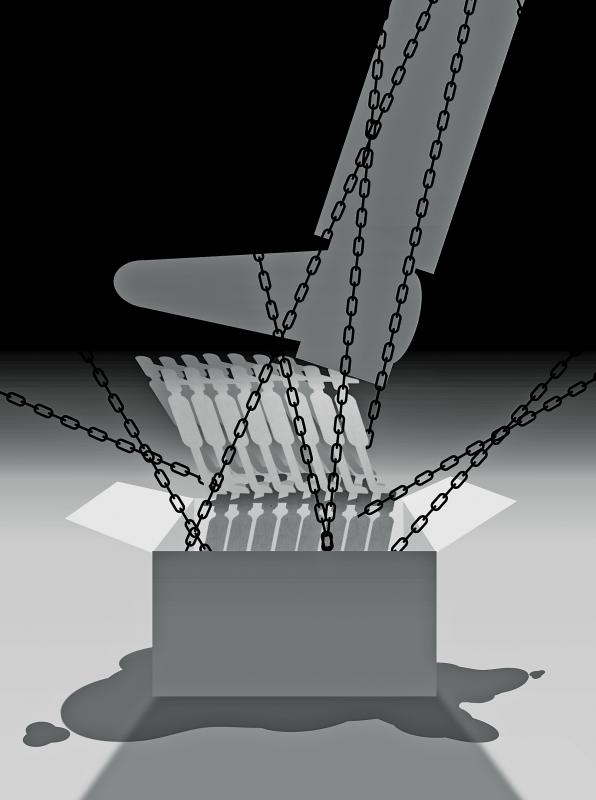

Illustration: Yusha

While Chiang Kai-shek’s (蔣介石) nationalists had begrudgingly accepted the official existence of five groups in the 1930s and 1940s, the communists recognized 55 in all (plus the Han majority), many with populations under 10,000.

A remarkable amount of time and capital was dedicated to the celebration and bolstering of these groups. Perhaps the largest social survey in human history sent thousands of researchers into minority communities, filling libraries with their reports. Linguists created writing systems for minorities who did not already have them.

The scale of the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) investment in groups it designated as “minorities” has been staggering.

Here is the irony: The Chinese communists do not believe that “ethnic identity” truly exists — not in the long run. Rooted in Marxism-Leninism, the party maintains — or at least, it did — that class is the only fundamental dimension of human identity. Other collective identities, such as nationality, religion and ethnicity are long-lasting but ultimately ephemeral fictions, constructed by those at the top of the economic pyramid to distract the poor from seeking comradeship with fellow proletarians.

Why would the party invest in something it does not think exists? To neutralize it.

While other countries have used denialism as a tactic to combat perceived threats of internal ethnic diversity — insisting on the singularity and indivisibility of one’s nation by recognizing as few minorities as possible, or perhaps none at all — the Chinese communist game plan was the opposite: to recognize ethnic diversity into irrelevance; to shepherd it into extinction.

By embracing so many ethnic identities, the goal has been to pre-empt threats of local nationalism; to ensure that the country’s minority nationalities never aspire to national self-determination or nation states. After all, if the state was recognizing and championing minority groups, what legitimate reason would anyone have to break off and form their own political entity?

A slow-acting process of disintegration was supposed to unfold, less a fiery melting pot than a leisurely slow cooker. Identities once important enough to declare independence over, even to die for, were supposed to matter less and less in people’s daily lives.

The goal was technically not assimilationist. A century from now — even 200 or 500 years — there should still be Tibetans, Uighurs, Miao and so on, but these monikers should not matter, except on festive occasions.

The plan has been remarkably effective. For some minority groups, such as the Manchu and Zhuang, it is not uncommon for people to speak nothing but flawless Mandarin.

Meanwhile, the provinces of Yunnan, Guangxi and Guizhou — once sites to some of the bloodiest ethnic violence in world history — have been transformed into “colorful” and “harmonious” lands of diverse cultures ready to welcome authenticity-seeking tourists.

This plan is not benign or nonviolent, let us be clear. The occupation of Tibet in 1951, the suppression of the 1958 Amdo Rebellion, and many other episodes demonstrate the bloody extent to which the state has gone and would go to maintain control.

Moreover, ethnic violence was widespread during the Cultural Revolution in 1966, as Maoist fanatics defaced mosques, dynamited Tibetan temples and attacked those wearing ethnic clothing — vestiges of the “old China” they sought to destroy.

However, as violent as these moments were, they were episodic and short-lived. Each time, the state snapped back to the earlier playbook of celebration and neutralization.

What happened? How did mass detention, the systematic destruction of mosques and imprisonment for showing signs of Muslim religiosity become state policy in Xinjiang?

Three reasons, primarily: growing inequality, the forces unleashed by China’s experiment with capitalism and the rise of ethnic scapegoating, fueled by rampant Han Chinese resentment.

The CCP’s ethno-political game plan has always depended on the gulf between rich and poor growing smaller, not larger.

Within the Han Chinese majority, as many basic aspects of the “Chinese dream” fall out of reach — for instance, even graduates of prestigious universities huddle in cramped apartments in the outskirts of cities they cannot afford to live in — resentment and intolerance has increased. It is not uncommon to find people taking aim online at affirmative action policies and the celebration of minorities.

While the party has long policed Han nationalism — or “chauvinism” as it still calls it — the sheer scale of this angry Han Chinese malaise is beyond anything Beijing ever planned for.

Meanwhile, when minority regions continue to fall behind the coastal Han provinces, and when lucrative local jobs go to internal Han migrants, a tiny subset find their way back to the always present, destabilizing potentials of ethnic identity: separatism, national self-determination, transnationalism and other things that keep party members up at night.

Even for those without any separatist ambitions — by far the majority of minorities — capitalist forces have turned ethnic identity into a form of commodity: a product that, in some locales, is their only “cash crop.” Capitalism has made ethnic identity more volatile and more resistant to the party’s hoped-for disintegration.

This is the forest fuel, collecting over many years of drought, that caught fire in the 21st century. Sept. 11, 2001, the 2009 protests that turned into riots in Urumqi, Xinjiang, and the 2014 Kunming rail station attack: These events provided the justification for Beijing’s brutal clampdown on Muslim Uighurs in the name of its “people’s war on terror.” They triggered a weakening, perhaps an abandonment, of ethnic policies that served the party for half a century, and which it spent a fortune building.

Will things snap back, as they did before? It is doubtful. The about-face in CCP ethno-politics seems to be melding with other, powerful forces. China’s multitrillion-dollar infrastructure gamble — the Belt and Road Initiative — marches straight through the north-west, where Xinjiang is. Climate migrants will need many places to go when sea water begins to fill the populous Pearl River Delta, among other regions.

Meanwhile, the “one country, two systems” approach to Hong Kong is essentially dead, and the PRC looks eerily close to contemplating military invasion of Taiwan. Should the party abandon the “56 nationalities of China” model, it would be just one more longstanding policy jettisoned in an already drastic list.

So again, the situation in Xinjiang was not “supposed” to happen. It might well augur the end of China’s ethnic diversity policies. As for what could replace them, the prospects seem grim.

Thomas S. Mullaney is a professor of Chinese history at Stanford University.

China has not been a top-tier issue for much of the second Trump administration. Instead, Trump has focused considerable energy on Ukraine, Israel, Iran, and defending America’s borders. At home, Trump has been busy passing an overhaul to America’s tax system, deporting unlawful immigrants, and targeting his political enemies. More recently, he has been consumed by the fallout of a political scandal involving his past relationship with a disgraced sex offender. When the administration has focused on China, there has not been a consistent throughline in its approach or its public statements. This lack of overarching narrative likely reflects a combination

Behind the gloating, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) must be letting out a big sigh of relief. Its powerful party machine saved the day, but it took that much effort just to survive a challenge mounted by a humble group of active citizens, and in areas where the KMT is historically strong. On the other hand, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) must now realize how toxic a brand it has become to many voters. The campaigners’ amateurism is what made them feel valid and authentic, but when the DPP belatedly inserted itself into the campaign, it did more harm than good. The

US President Donald Trump’s alleged request that Taiwanese President William Lai (賴清德) not stop in New York while traveling to three of Taiwan’s diplomatic allies, after his administration also rescheduled a visit to Washington by the minister of national defense, sets an unwise precedent and risks locking the US into a trajectory of either direct conflict with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) or capitulation to it over Taiwan. Taiwanese authorities have said that no plans to request a stopover in the US had been submitted to Washington, but Trump shared a direct call with Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平)

Workers’ rights groups on July 17 called on the Ministry of Labor to protect migrant fishers, days after CNN reported what it described as a “pattern of abuse” in Taiwan’s distant-water fishing industry. The report detailed the harrowing account of Indonesian migrant fisher Silwanus Tangkotta, who crushed his fingers in a metal door last year while aboard a Taiwanese fishing vessel. The captain reportedly refused to return to port for medical treatment, as they “hadn’t caught enough fish to justify the trip.” Tangkotta lost two fingers, and was fired and denied compensation upon returning to land. Another former migrant fisher, Adrian Dogdodo