As crunch UN talks to reverse the accelerating destruction of nature loom, indigenous communities are sounding an alarm over proposed conservation plans that they say could clash with their rights.

The COP-15 UN biodiversity summit in Kunming, China — provisionally slated for early October — will see nearly 200 nations attempt to thrash out new goals to preserve Earth’s battered ecosystems.

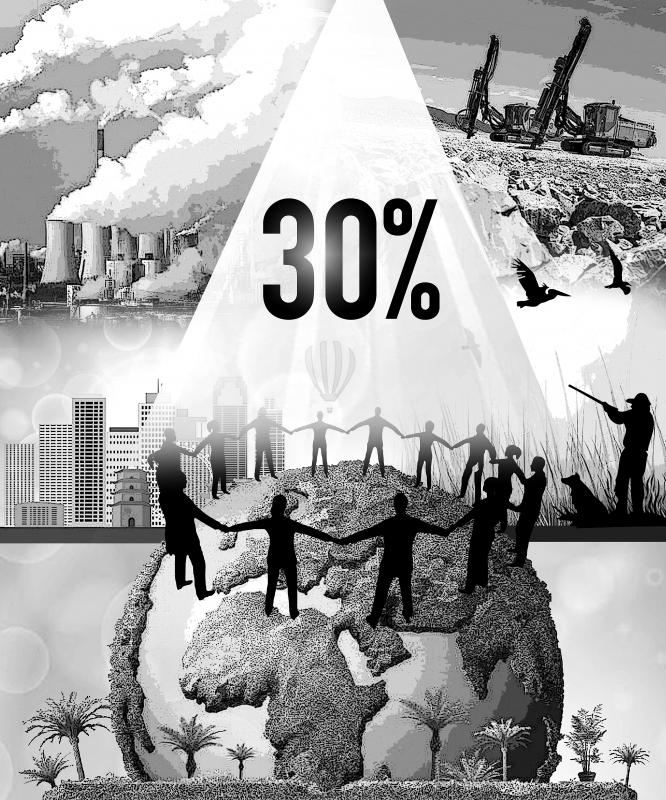

To limit the devastating effects of species loss caused by pollution, hunting, mining, tourism and urban sprawl, the draft treaty proposes to create protected areas covering 30 percent of the planet’s lands and oceans by 2030.

Illustration: Constance Chou

On Monday last week, global leaders from more than 50 countries pledged at the One Planet Summit to back the plan, which could become the cornerstone of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) meeting in China.

However, the past experience of indigenous populations has made them wary of the proposal. Earlier efforts to create protected areas such as national parks sometimes led to their eviction from ancestral lands.

“By just setting a target without adequate standards and commitment to accountability mechanisms, the CBD could unleash another wave of colonial land grabbing that disenfranchises millions of people,” Rights and Resources Initiative coordinator Andy White said.

For example, when the Kahuzi-Biega National Park in the Democratic Republic of the Congo was dramatically enlarged in 1975, the Bambuti community lost more than access to the forest. A whole culture intertwined with nature perished.

“We no longer have access to medicinal plants,” Integrated Programme for the Development of the Pygmy People regional director Diel Mochire said. “Our diet changed. In the forest, we had easy access to resources. Now we have to buy everything.”

The first conservation-related evictions date back to the 19th century, when the US government violently expelled Native Americans from lands that became the Yellowstone and Yosemite national parks.

“That model was exported around the world,” White said, adding that it is still the dominant model.

The Rights and Resources Initiative, which defends indigenous communities’ rights, estimates that 136 million people have so far been displaced globally during the creation of the world’s protected areas, which cover about 8.5 million square kilometers.

It further calculates that more than 1.6 billion people could be affected — directly or indirectly — by the so-called “30-30” initiative.

A 2016 report by the UN concluded that some of the world’s leading conservation groups had violated the rights of some indigenous communities by backing conservation projects that ousted them from ancestral homes.

A 2019 Buzzfeed investigation implicated the WWF in serious rights abuses — including torture and murder — carried out by rogue anti-poaching units in national parks in Asia and Africa.

An independent audit released in November last year found that none of the group’s staff participated in abuses, but that the WWF should be “more transparent” and must more firmly engage governments to uphold human rights.

WWF said that it would “do more.”

Scientists and environmental groups alike are increasingly emphasizing indigenous communities’ role in conservation.

However, efforts to protect and restore nature on a global scale have spectacularly failed.

Most scientists agree that the planet is on the cusp of a mass extinction event, in which species are vanishing at 100 to 1,000 times the normal “background” rate.

The UN’s science advisory panel for biodiversity, called IPBES, said in a 2019 landmark report that 1 million species face extinction, due mostly to habitat loss and over-exploitation.

Indigenous communities’ know-how represents a glimmer of hope in an otherwise bleak picture, the same report found.

IPBES said that at least one-quarter of global lands are traditionally owned, managed or occupied by indigenous communities.

“Within that 25 percent, the lands managed by indigenous peoples tend to have less biodiversity loss,” said Pamela McElwee, a lead author of the report.

Research has shown that forests under indigenous management are more effective at storing carbon and are less prone to wildfires than many “protected areas” controlled by business concessions.

Private companies that manage huge tracts of forests under a UN-approved financial mechanism to curb deforestation — known as Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation — too often bulldoze the rights of forest-dwelling communities, earlier research has shown.

Indigenous communities are “disproportionately attacked for standing up for their rights and territories,” watchdog Global Witness said in July last year.

In 2019, a record 212 environmental campaigners, nearly half from indigenous communities, were murdered around the world, the group’s annual tally showed.

Major conservation groups ranging from the International Union for Conservation of Nature to the WWF emphasize the importance of indigenous communities’ role in conservation.

“WWF firmly believes that we will only be able to halt and reverse our unprecedented loss of nature if we work hand in hand with indigenous peoples and local communities,” the group said in a statement.

“The biggest single determinant of success in conservation is ... having the rights included and having something that’s bottom up,” International Union for Conservation of Nature program development manager James Hardcastle said. “That’s where you will be successful on all accounts — you’ll be able to defend the rights, territory, integrity, the ecological functions or species in the area.”

Canadian Basile van Havre, cochair of the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) said: “The CBD makes ample room for indigenous peoples.”

However, indigenous leaders have yet to be convinced that a shift in narrative is to translate into a change in practice.

“Until I see action, I will not believe it,” said Peter Kitelo, a 45-year-old telecommunications engineer from the Ogiek community in Kenya. “Most conservation organizations have perfected the art of public relations.”

The draft treaty for the COP15 summit says that 30 percent of the planet should be covered by “protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures.”

For Hardcastle, “other effective” measures could include governance by indigenous communities.

Mochire said that he is not necessarily opposed to expanding protected areas, but needs to see how the measures would be carried out.

“We are currently putting forward proposals to the government on how to get there without damaging communities,” he said.

The COP15 treaty should enshrine indigenous communities’ land rights and devise accountability mechanisms to ensure that expanded protected areas do not lead to human rights violations, White said.

“In many cases local people cannot complain to their own governments when they are abused by the national park service,” White said. “So they need to have recourse through the international arena.”

Recently, China launched another diplomatic offensive against Taiwan, improperly linking its “one China principle” with UN General Assembly Resolution 2758 to constrain Taiwan’s diplomatic space. After Taiwan’s presidential election on Jan. 13, China persuaded Nauru to sever diplomatic ties with Taiwan. Nauru cited Resolution 2758 in its declaration of the diplomatic break. Subsequently, during the WHO Executive Board meeting that month, Beijing rallied countries including Venezuela, Zimbabwe, Belarus, Egypt, Nicaragua, Sri Lanka, Laos, Russia, Syria and Pakistan to reiterate the “one China principle” in their statements, and assert that “Resolution 2758 has settled the status of Taiwan” to hinder Taiwan’s

Can US dialogue and cooperation with the communist dictatorship in Beijing help avert a Taiwan Strait crisis? Or is US President Joe Biden playing into Chinese President Xi Jinping’s (習近平) hands? With America preoccupied with the wars in Europe and the Middle East, Biden is seeking better relations with Xi’s regime. The goal is to responsibly manage US-China competition and prevent unintended conflict, thereby hoping to create greater space for the two countries to work together in areas where their interests align. The existing wars have already stretched US military resources thin, and the last thing Biden wants is yet another war.

As Maldivian President Mohamed Muizzu’s party won by a landslide in Sunday’s parliamentary election, it is a good time to take another look at recent developments in the Maldivian foreign policy. While Muizzu has been promoting his “Maldives First” policy, the agenda seems to have lost sight of a number of factors. Contemporary Maldivian policy serves as a stark illustration of how a blend of missteps in public posturing, populist agendas and inattentive leadership can lead to diplomatic setbacks and damage a country’s long-term foreign policy priorities. Over the past few months, Maldivian foreign policy has entangled itself in playing

A group of Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers led by the party’s legislative caucus whip Fu Kun-chi (?) are to visit Beijing for four days this week, but some have questioned the timing and purpose of the visit, which demonstrates the KMT caucus’ increasing arrogance. Fu on Wednesday last week confirmed that following an invitation by Beijing, he would lead a group of lawmakers to China from Thursday to Sunday to discuss tourism and agricultural exports, but he refused to say whether they would meet with Chinese officials. That the visit is taking place during the legislative session and in the aftermath