Developing a COVID-19 vaccine in record time will be tough. Producing enough to end the pandemic will be the biggest medical manufacturing feat in history.

That work is under way.

From deploying experts amid global travel restrictions to managing extreme storage conditions, and even inventing new kinds of vials and syringes for billions of doses, the path is strewn with formidable hurdles, according to Reuters interviews with more than a dozen vaccine developers and their backers.

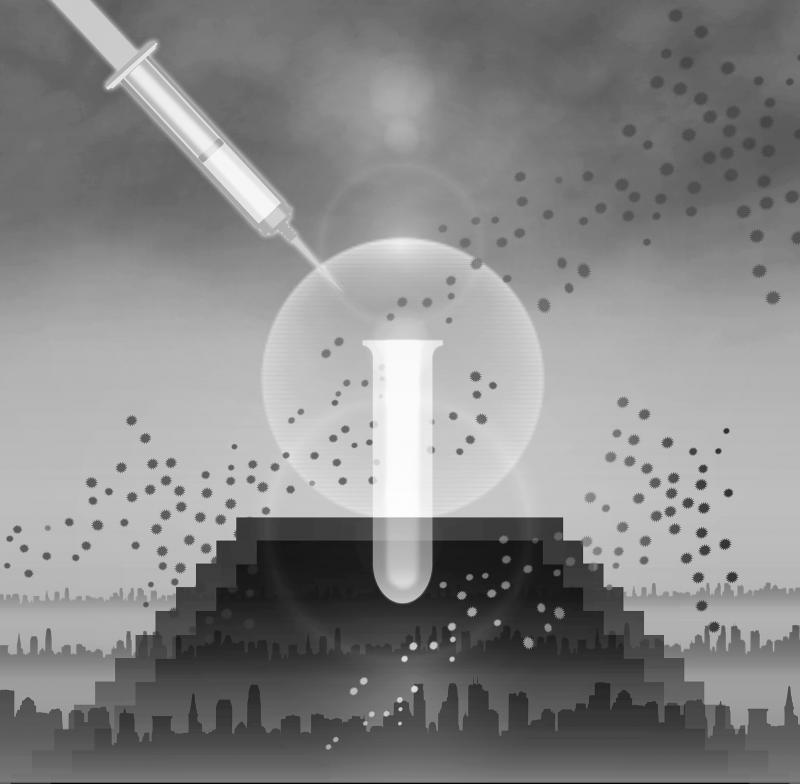

Illustration: Yusha

Any hitch in an untested supply chain — which could stretch from Pune in India to England’s Oxford and Baltimore in the US — could torpedo or delay the complex process.

Colonel Nelson Michael, director of the US Army’s Center for Infectious Disease Research who is working on the government’s “Warp Speed” project to deliver a vaccine at scale by January, said companies usually have years to figure this stuff out.

“Now, they have weeks,” he said.

Much of the world’s attention is focused on the scientific race to develop a vaccine. But behind the scenes, experts are facing a stark reality: We may simply not have enough capacity to make, package and distribute billions of doses all at once.

Companies and governments are racing to scale up machinery to address a critical shortage in automated filling and finishing capacity — the final step in the manufacturing process of putting the vaccine into vials or syringes, sealing them and packaging them up for shipping.

“This is the biggest logistical challenge the world has ever faced,” said Toby Peters, an engineering and technology expert at Britain’s Birmingham University. “We could be looking at vaccinating 60 percent of the population.”

Several developers, including frontrunner Moderna, are experimenting with new ways to mitigate the extreme cold storage demands of their vaccines, which at present need to be kept at minus-80oC.

SiO2 Materials Science is working on producing vials that will not shatter at super-cold temperatures.

Travel restrictions, meanwhile, are posing more prosaic problems: For example, Johnson & Johnson, which plans to start clinical trials this summer, has struggled to send its vaccine experts to oversee the launch of production sites.

‘NEVER IN HISTORY’

By setting up massive clinical trials involving 10,000 to 30,000 volunteers per vaccine, scientists hope to get an answer on whether a vaccine works as early as this October. However, even if they succeed, manufacturing in bulk, getting regulators to sign off and packaging billions of doses are a monumental challenge.

GAVI vaccines alliance chief executive Seth Berkley said that in reality, the world is unlikely to go straight from having zero vaccines to having enough doses for everyone.

“It’s likely to be a tailored approach to start with,” he said in an interview. “We’re looking to have something like 1 to 2 billion doses of vaccine in the first year, spread out over the world population.”

J&J has partnered with the US government on a US$1 billion investment to speed development and production of its vaccine, even before it is proven to work. It has contracted Emergent Biosolutions and Catalent to manufacture in bulk in the US. Catalent will also do some fill-and-finish work.

“Never in history has so much vaccine been developed at the same time — so that capacity doesn’t exist,” said Paul Stoffels, J&J’s chief scientific officer who sees filling capacity as the main limiting factor.

Emergent’s manufacturing plant in Bayview, Maryland, can accommodate four vaccines in parallel using different manufacturing platforms and equipment.

Funded by the government in 2012, the plant includes single-use disposable bioreactor equipment featuring plastic bags rather than stainless steel fermentation equipment, which makes it easier to switch from one vaccine to another.

This month, the company received an additional US$628 million to make those four suites available to support any candidate the government selects, chief executive Bob Kramer said.

BLOW-FILL-SEAL-REPEAT

As well as working with J&J, New Jersey-based Catalent signed a deal with British drugmaker AstraZeneca earlier this month to provide vial-filling and packaging services at its plant in Anagni, Italy.

It aims to handle hundreds of millions of doses, starting as early as August and possibly running until March 2022.

It has ordered high-speed vial-filling equipment to boost output at its Indiana plant, where it is also hiring an additional 300 workers.

Catalent’s North American president for biologics Michael Riley said his biggest challenge was trying to compress work that normally takes years into months.

Adding to the challenge is that glass vials are in short supply.

To save glass, companies plan to use larger vials of 5 to 20 doses — but this raises new problems, such as potential waste, if not all the doses are used before the vaccine spoils.

“The downside is that after a healthcare practitioner opens a vial, they need to then vaccinate 20 people in a short, 24-hour time,” said Prashant Yadav, a global healthcare supply chain expert at the Center for Global Development in Washington.

As part of the same drive, the US Department of Health and Human Services and the Department of Defense have awarded ApiJect Systems up to US$138 million to upgrade its facilities to be able to make up to 100 million plastic pre-filled syringes by the end of this year, and as many as 600 million next year.

The company plans to use a technology called Blow-Fill-Seal, where syringes are blown out of plastic, filled with vaccine and sealed in seconds.

This will need US Food and Drug Administration approval, ApiJect chief executive Jay Walker said.

BREAKING COLD CHAIN

SiO2 Materials Science is ramping up capacity of plastic vials with a glass lining, which are more stable at ultra-low temperatures.

“You can bring us down to minus-196oC, which none of the vaccines need,” chief business officer Lawrence Ganti said. “You can throw it against the wall and it doesn’t break. Our founder has done that. He’s thrown frozen vials at me.”

The company expects to boost production from the current 5 million to 10 million vials a year to 120 million within three-and-a-half months, he said.

Once packaged, many vaccines need to be kept cold — and some leading contenders made from genetic material, such as messenger RNA, need to be kept very cold — presenting another challenge that may limit access.

“People who work with mRNA store it at minus-80oC, which is not something you’re gonna find in most pharmacies or doctor’s offices,” said Paul Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and co-inventor of the rotavirus vaccine.

Peters has been gathering data from poorer regions of Africa and Asia, and said breaks in the temperature-controlled supply chain — “cold chain” — are already frequent.

In some places, it is common to lose 25 percent or more of vaccines because of broken cold chains, he said.

“So if you’re looking to manufacture 4 billion, and you reckon you’re going to lose 25 percent, then you have to manufacture 5 billion,” he said. “It’s all the elements to move it from the point of manufacture to the point of aggregation, right down to the health centers and then out to the community.”

QUARANTINE QUAGMIRE

Companies developing mRNA vaccines, including Moderna and Translate Bio, which is partnering with Sanofi, are working to make candidates stable at higher temperatures.

Translate Bio chief executive Ron Renaud said he was confident this would happen “within a short amount of time.”

“We are getting more confident that we could run our supply chain at minus-20oC, which is an easier storage condition than deep freezing,” Moderna spokeswoman ModerColleen Hussey said.

Moderna plans to add a small period of time in which the vaccine can be stored at normal fridge temperatures of 2 to 8oC in doctors’ offices or clinics.

“We will know more in the next two to three months,” she said.

The pandemic is also presenting obstacles of a less technical nature.

Catalent, which has about 30 plants worldwide, has had to write special permission slips in eight languages explaining that its workers are considered essential.

J&J is having trouble getting experienced personnel to far-flung labs to oversee the transfer of technology to contract manufacturers because they are subject to 14-day quarantines.

“It is absolutely a factor,” Stoffels said. “If you have to send your people to the middle of India to get to filling capacity, that’s not easy at the moment.”

As the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and its People’s Liberation Army (PLA) reach the point of confidence that they can start and win a war to destroy the democratic culture on Taiwan, any future decision to do so may likely be directly affected by the CCP’s ability to promote wars on the Korean Peninsula, in Europe, or, as most recently, on the Indian subcontinent. It stands to reason that the Trump Administration’s success early on May 10 to convince India and Pakistan to deescalate their four-day conventional military conflict, assessed to be close to a nuclear weapons exchange, also served to

The recent aerial clash between Pakistan and India offers a glimpse of how China is narrowing the gap in military airpower with the US. It is a warning not just for Washington, but for Taipei, too. Claims from both sides remain contested, but a broader picture is emerging among experts who track China’s air force and fighter jet development: Beijing’s defense systems are growing increasingly credible. Pakistan said its deployment of Chinese-manufactured J-10C fighters downed multiple Indian aircraft, although New Delhi denies this. There are caveats: Even if Islamabad’s claims are accurate, Beijing’s equipment does not offer a direct comparison

After India’s punitive precision strikes targeting what New Delhi called nine terrorist sites inside Pakistan, reactions poured in from governments around the world. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) issued a statement on May 10, opposing terrorism and expressing concern about the growing tensions between India and Pakistan. The statement noticeably expressed support for the Indian government’s right to maintain its national security and act against terrorists. The ministry said that it “works closely with democratic partners worldwide in staunch opposition to international terrorism” and expressed “firm support for all legitimate and necessary actions taken by the government of India

Minister of National Defense Wellington Koo (顧立雄) has said that the armed forces must reach a high level of combat readiness by 2027. That date was not simply picked out of a hat. It has been bandied around since 2021, and was mentioned most recently by US Senator John Cornyn during a question to US Secretary of State Marco Rubio at a US Senate Foreign Relations Committee hearing on Tuesday. It first surfaced during a hearing in the US in 2021, when then-US Navy admiral Philip Davidson, who was head of the US Indo-Pacific Command, said: “The threat [of military