The COVID-19 pandemic is forcing senior doctors in the British National Health Service (NHS) to contemplate the unthinkable: How to ration access to critical care beds and ventilators should resources fall short.

The country’s public health system is ill-equipped to cope with an outbreak that is unprecedented in modern times.

Hospitals are now striving to at least quadruple the number of intensive care beds to meet an expected surge in serious virus cases, senior physicians told reporters, but expressed dismay that preparations had not begun weeks earlier.

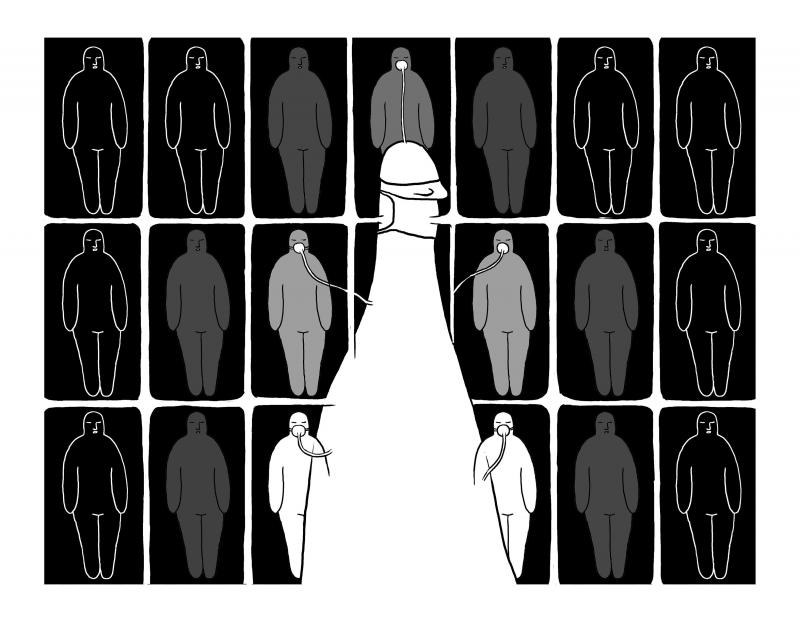

Illustration: Mountain People

With serious shortages of ventilators, protective equipment and trained workers, the physicians said senior staff at hospitals were beginning to confront an excruciating debate on intensive care rationing, although the UK might be a long way from potentially having to make such decisions.

Rahuldeb Sarkar, a consultant physician in respiratory medicine and critical care in the English county of Kent, said that local NHS trusts across the country were reviewing decisionmaking procedures drawn up, but never needed, during the 2009 H1N1 flu pandemic. They cover how to choose who, in the event of a shortage, would be put on a ventilator and for how long.

Decisions would always be based on an individual basis if it got to that point, taking into account the chance of survival, he said.

However, nevertheless, there would be difficult choices.

“It will be tough and that’s why it’s important that you know that two or more consultants will make the decisions,” he said.

Sarkar said that the choices extended not only to who was given access to a ventilator, but how long to continue if there was no sign of recovery.

“In normal days, that patient would be given some more days to see which way it goes,” he added.

However, if the worst predictions about the spread of the virus proved correct, he suspected “it will happen quicker than before.”

The UK is by no means the only country that faces having its health system overwhelmed by COVID-19, but the data on critical care beds — a crucial bulwark against the disease — are concerning for UK authorities.

Italy, where the coronavirus has driven hospitals to the point of collapse in some areas and thousands have died, had about 12.5 critical care beds per 100,000 of its population before the outbreak.

That is above the European average of 11.5, while the figure in Germany is 29.2, according to a widely quoted academic study dating back to 2012, which doctors said was still valid. The UK has 6.6.

Estimates of the potential death toll in the UK range from a government estimate of about 20,000 to an upper end of more than 250,000 predicted by researchers at Imperial College.

As of Thursday last week, 64,621 people had been tested, with 3,269 positive.

The NHS is preparing for the biggest challenge it has faced since it was founded after the ravages of World War II, promising cradle-to-grave healthcare for all.

It was stretched long before COVID-19, struggling to adapt to the vast increase in healthcare demand in the past few years. Some doctors complain that it is underfunded and poorly managed. About one-10th of more than 1 million staff roles in the health service are vacant, while almost nine out of 10 beds are occupied.

British Prime Minister Boris Johnson was asked at a media conference on Friday, after Reuters reported the concerns of physicians, whether the UK could get to a stage where NHS workers had to choose who to save because there were not enough ventilators.

He urged people to follow public safety measures.

“The objective of this whole campaign is to ensure we flatten the curve, as we have been saying repeatedly over the last couple of weeks, but also that we lift up the line of NHS resilience and capabilities,” he said.

“That means there is a massive effort going on right now to make sure we do have enough ventilators and ICUs to cope,” he added.

So how many life-saving ventilators are needed?

British Secretary of State for Health and Social Care Matt Hancock on Sunday said that hospitals had about 5,000, but that they needed “many times more than that.”

The physicians interviewed by reporters said that, if ventilators were secured, the aim was to increase intensive care beds from about 4,200 to more than 16,000, partly by using beds in other parts of hospitals.

Rob Harwood, a consultant anesthetist in Norfolk who has worked in the health service for almost four decades, said that access to critical care could ultimately have to be determined by patient scoring systems for survivability.

Systems developed for SARS, another coronavirus, which broke out in 2003, could for example be refined, he added.

“Once you have exhausted your capacity and exhausted your ability to expand your capacity you probably have to make other decisions about admission into intensive care,” he said.

However, for now, admission criteria would stay unaltered.

“We are a country mile from that at the moment,” Harwood said.

While shortages of critical care equipment might be most alarming, the coronavirus has exposed how generally ill-equipped the health system is for a pandemic.

The British Medical Association said that doctors have been asked to go to hardware stores and building sites to source protective masks.

Some doctors are worried about Public Health England’s (PHE) advice last week that reduces the level of the protective equipment they need to wear.

Previously, staff on ward visits were told to wear full protective equipment, comprising high-quality FFP3 face masks, visors, surgical gowns and two pairs of gloves.

However, the new advice recommends only a lower-quality standard paper surgical mask, short gloves and a plastic apron.

PHE referred queries about doctors’ worries to the health department, which did not respond to requests for comment on the matter.

A senior NHS epidemiologist, who was not permitted to be named, told reporters that this advice was based on a sensible assessment of the biohazard risk of the virus.

“It’s not Ebola,” the doctor said, pointing out the risk to medical staff without underlying medical conditions was low.

Matt Mayer, head of the local medical committee covering an area in south of England, said general physicians had been sent masks in boxes that said “best before 2016” and that have been relabeled with new stickers reading “2021.”

“If you are going to lead people into a hazardous situation, then you need to give them the confidence that they have the kit to do a decent job and they are not just going to become cannon fodder,” Harwood said.

The department of health said that it had tested certain products to see if it is possible to extend their use.

“The products that pass these stringent tests are subject to relabeling with a new shelf life as appropriate and can continue to be used,” a spokesman said.

Alison Pittard, dean of the Faculty of Intensive Medicine and a consultant in Leeds, England, said that there had been chronic underinvestment in critical care in the UK.

However, she said the country was not yet at the stage where it had to make calls about rationing patient resources.

If rationing became necessary, medical ethics should still prevail and guidelines needed to be issued on a national level so that no patient was worse off based on where they lived, she said.

The NHS might also need the advice of military leaders, she said, on how to effectively triage.

“If we got to a difficult position where we had to exhaust every bit of resource in the country then, yes, we may have to change the way we approach the decisionmaking,” Pittard said.

Stephen Powis, the national medical director of NHS England, said that there were plans to issue new guidance to give doctors advice on how to make difficult decisions if there was a surge in coronavirus cases, like in Italy.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence on Friday said that it would shortly announce a “series of rapid guidelines” on the management of people with suspected and confirmed COVID-19, including in critical care.

However, the guidelines are not expected to be prescriptive, but to suggest leaving key decisions to individual doctors.

Pittard said that patients with pre-existing conditions who already had life-threatening health difficulties should be having conversations with their family about how they wished to spend their last days, in the event of them being infected.

“If I get coronavirus now I’ve got a very high chance of dying of it,” she said, putting herself into the shoes of such a patient. “So do I want to die in hospital and when my relatives can’t come in to visit me because it’s too risky, or would I like to die at home?

“And if I do want to go into hospital, do I then want to go to intensive care where my chances of surviving are minimal?” she said.

Congratulations to China’s working class — they have officially entered the “Livestock Feed 2.0” era. While others are still researching how to achieve healthy and balanced diets, China has already evolved to the point where it does not matter whether you are actually eating food, as long as you can swallow it. There is no need for cooking, chewing or making decisions — just tear open a package, add some hot water and in a short three minutes you have something that can keep you alive for at least another six hours. This is not science fiction — it is reality.

A foreign colleague of mine asked me recently, “What is a safe distance from potential People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Rocket Force’s (PLARF) Taiwan targets?” This article will answer this question and help people living in Taiwan have a deeper understanding of the threat. Why is it important to understand PLA/PLARF targeting strategy? According to RAND analysis, the PLA’s “systems destruction warfare” focuses on crippling an adversary’s operational system by targeting its networks, especially leadership, command and control (C2) nodes, sensors, and information hubs. Admiral Samuel Paparo, commander of US Indo-Pacific Command, noted in his 15 May 2025 Sedona Forum keynote speech that, as

In a world increasingly defined by unpredictability, two actors stand out as islands of stability: Europe and Taiwan. One, a sprawling union of democracies, but under immense pressure, grappling with a geopolitical reality it was not originally designed for. The other, a vibrant, resilient democracy thriving as a technological global leader, but living under a growing existential threat. In response to rising uncertainties, they are both seeking resilience and learning to better position themselves. It is now time they recognize each other not just as partners of convenience, but as strategic and indispensable lifelines. The US, long seen as the anchor

Kinmen County’s political geography is provocative in and of itself. A pair of islets running up abreast the Chinese mainland, just 20 minutes by ferry from the Chinese city of Xiamen, Kinmen remains under the Taiwanese government’s control, after China’s failed invasion attempt in 1949. The provocative nature of Kinmen’s existence, along with the Matsu Islands off the coast of China’s Fuzhou City, has led to no shortage of outrageous takes and analyses in foreign media either fearmongering of a Chinese invasion or using these accidents of history to somehow understand Taiwan. Every few months a foreign reporter goes to