At Karet Bivak Cemetery in Jakarta, the neat rows of headstones extend as far as the eye can see, seeming to sprout into skyscrapers at the horizon.

Driving his scooter through after Friday prayers, a friendly Muslim man wearing white robes and a taqiyah cap seems at peace with his fate.

“This is my future home,” he says, leaning on the handlebars and indicating the graves. “Your home, my home — everybody’s home.”

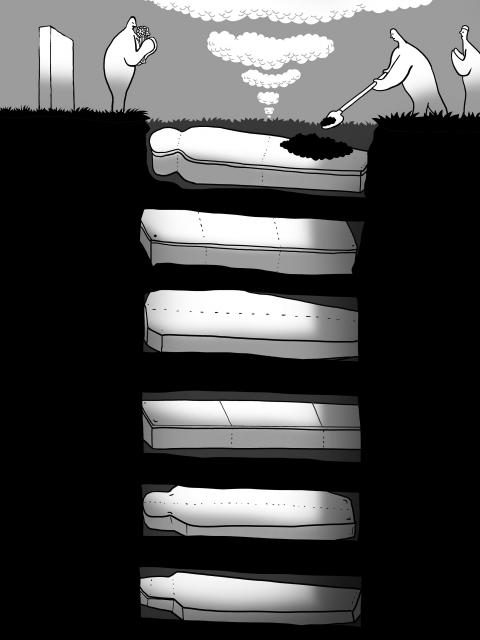

Illustration: Mountain People

That is no longer the case. Spread over 16 hectares of a former rubber plantation, Karet Bivak is Jakarta’s second-largest cemetery — and, like an increasing number across the city, it is full. Authorities froze new plots in November 2017 to prevent overcrowding. For now and the foreseeable future, the only way to be buried here is for your body to be stacked on top of another one.

Up to six people, typically from the same family, are being buried in a space originally designated for one. There are now about 100,000 bodies in 48,400 plots.

It is a stopgap solution to a shortage of burial land in a city where overcrowding above ground is increasingly extending below it. Of 84 public cemeteries, a quarter have stopped licensing new plots, limiting burials to those with written permission to join an existing one.

Meanwhile, the number of cemeteries stacking bodies, known as makam tumpeng — “overlapping graves” — was reported as 16 in August, and is now confirmed at 20.

Bodies can be stacked alongside or on top of each other, according to the municipal policy, with a minimum of 1m between them. Plots must also be at least three years old before another body can be added, by which point only a skeleton remains.

The head of Karet Bivak, Saiman — who, like many Indonesians, goes by one name — says that stacking is no issue for the dead: Problems only arise among the living.

There have been graveside conflicts when one of the bereaved has realized too late that the deceased is joining an occupied plot, he says.

Family rifts have also been weaponized by the requirement for written permission from the license holder.

One woman refused to allow her late ex-husband use of the family plot because he had remarried, Jakarta Forestry Agency funeral service unit Ricky Putra says.

In another case, a man wanted to be buried on top of his uncle, but his cousin blocked him due to jealousy.

As the overcrowding issue emerged about three years ago, the department has worked hard to educate the public about its stacking solution, Putra says.

As well as articles in the press and social media, Karet Bivak hung banners in the lead-up to Ramadan — the busiest time of year for Muslim cemeteries, when thousands make a pilgrimage to loved ones’ graves.

Jakarta’s high population density means that most public cemeteries are boxed in by buildings, with regulations further preventing their expansion. In south Jakarta, the Kalibata Heroes Cemetery is converting its gardens into graves, to expand its capacity by 900.

“It is very hard to get land for a cemetery, or even development of infrastructure,” says Rangi Faridha, an architect on the city planning and development board. “There are many factors, but the biggest one is that people don’t want to sell their land.”

Long before they started stacking, cemeteries also dug up “expired” graves, ones where licenses had been allowed to lapse. About 20,000 plots at Karet Bivak were freed up in this way — but as with stacking, this policy can only do so much to meet demand.

The growing number of public cemeteries reaching capacity is a concern, but not a crisis, says Putra in his office, the files behind him piled almost to the ceiling as if to undermine his claims.

The city still has 200 hectares of land in reserve for cemeteries, he says, pulling up pictures on his smartphone of a 20-hectare area under development in north Jakarta — a stretch of swampland that is slated to open in 2021.

However, with 80 to 100 bodies being received at public cemeteries every day, the issue continues to be pressing, particularly for poorer Jakartans.

Five of the 20 full cemeteries are in east Jakarta, where the city’s poverty rate is highest. Public cemeteries typically charge about 100,000 Indonesian rupiah (US$7.12) for burial in a new plot, and then a smaller license fee every three years — for perspective, the poverty line is set at 400,000 rupiah per month.

Most poorer people seek to send their dead to the one closest to their home, in the interests of convenient visits and lowering costs — but if your closest public cemetery is full, you must incur the extra costs yourself of traveling further afield. Even ambulances charge a fee.

Private cemeteries are popping up for those who can afford them, including “luxury parks” such as San Diego Hills in Karawang, West Java, where a burial — including coffin, embalming, certification and license — can cost more than 26 million rupiah, Saiman says.

At Karet Bivak, it costs between 10,000 and 25,000 rupiah to license a plot for three years, but for extra care, there are hundreds of informal caretakers — often below the poverty line themselves — who make their living providing grave maintenance as “freelancers,” and in many cases live in the cemetery itself, Saiman says.

In east Jakarta, the predominantly Chinese Kebon Nanas Cemetery is home to as many as 200 people.

With its active service economy — signposted subdivisions as well as food carts and stalls at each gate — the cemetery is like a central neighborhood. For many residents, it is also their most accessible open green space.

Jakarta has less than 5 percent green space, forcing people in search of respite from the pace and pollution of the city into cemeteries. Last year, a party in an east Jakarta graveyard, complete with sound system and marquees, prompted a rebuke from the city administration.

Building more cemeteries could be a huge opportunity for the city, says Mohamad Reza Mohamed Afla, a senior lecturer at Universiti Sains Malaysia in Penang who specializes in burial land management.

Cities across Southeast Asia are facing the same issue of overcrowding — in Singapore, stacking has been mandated for many years, while Kuala Lumpur is considering it — but he says that Jakarta is at an advantage in that many of its public cemeteries are centrally located, and residents and authorities recognize their value as public space.

“In Jakarta, the local people live close to them, so they really have a social value,” he says. “People just hang out there — in Kuala Lumpur, we don’t do that.”

Cemeteries also create jobs and help reduce the impact of heat, he says, adding that a truly livable city is one that ensures its residents’ well-being into the afterlife.

The conflict in the Middle East has been disrupting financial markets, raising concerns about rising inflationary pressures and global economic growth. One market that some investors are particularly worried about has not been heavily covered in the news: the private credit market. Even before the joint US-Israeli attacks on Iran on Feb. 28, global capital markets had faced growing structural pressure — the deteriorating funding conditions in the private credit market. The private credit market is where companies borrow funds directly from nonbank financial institutions such as asset management companies, insurance companies and private lending platforms. Its popularity has risen since

The Donald Trump administration’s approach to China broadly, and to cross-Strait relations in particular, remains a conundrum. The 2025 US National Security Strategy prioritized the defense of Taiwan in a way that surprised some observers of the Trump administration: “Deterring a conflict over Taiwan, ideally by preserving military overmatch, is a priority.” Two months later, Taiwan went entirely unmentioned in the US National Defense Strategy, as did military overmatch vis-a-vis China, giving renewed cause for concern. How to interpret these varying statements remains an open question. In both documents, the Indo-Pacific is listed as a second priority behind homeland defense and

Every analyst watching Iran’s succession crisis is asking who would replace supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. Yet, the real question is whether China has learned enough from the Persian Gulf to survive a war over Taiwan. Beijing purchases roughly 90 percent of Iran’s exported crude — some 1.61 million barrels per day last year — and holds a US$400 billion, 25-year cooperation agreement binding it to Tehran’s stability. However, this is not simply the story of a patron protecting an investment. China has spent years engineering a sanctions-evasion architecture that was never really about Iran — it was about Taiwan. The

For Taiwan, the ongoing US and Israeli strikes on Iranian targets are a warning signal: When a major power stretches the boundaries of self-defense, smaller states feel the tremors first. Taiwan’s security rests on two pillars: US deterrence and the credibility of international law. The first deters coercion from China. The second legitimizes Taiwan’s place in the international community. One is material. The other is moral. Both are indispensable. Under the UN Charter, force is lawful only in response to an armed attack or with UN Security Council authorization. Even pre-emptive self-defense — long debated — requires a demonstrably imminent