It was billed as one of the most important company-wide meetings in the history of Uber. Yet, as staff gathered on Tuesday last week at Uber’s headquarters in San Francisco, there was one very conspicuous absence.

“Let us address the elephant in the room,” said Arianna Huffington, perhaps the most high-profile member of Uber’s board. “Where is Travis?”

The answer: Travis Kalanick, Uber’s 40-year-old cofounder and chief executive, was taking a leave of absence from the ride-hailing app he has transformed into a global behemoth valued at almost US$70 billion.

Huffington told Uber’s staff that the company would not await Kalanick’s return, choosing instead to act immediately on the findings of a damning investigation, accepted by the board, into the company’s workplace culture amid claims of sexual harassment.

“Uber is his life,” she said of Kalanick. “He has taken full responsibility for what the company has gone through in the last few months and now he wants to be part of us turning a new page and together building the next chapter in Uber’s history.”

The embattled company had hit the reset button, without its controversial CEO, it would, Huffington declared, be “a new Uber.”

It lasted all of six minutes and 45 seconds, when another board member, venture capitalist David Bonderman, interjected with a sexist joke, saying that more women on the board means “it’s much more likely to be more talking.”

Within a few hours, Bonderman had resigned, the latest in a seemingly never-ending stream of company leaders and senior executives who have either been forced out or, more often, simply abandoned ship.

At about the time Uber’s San Francisco staff were informed that their chief executive was taking an indefinite break from his company, Dante was waking up in his car on a quiet street not far from downtown Los Angeles. The 28-year-old rolled up his sleeping bag, put it in the trunk with his pillow and drove off to get breakfast before picking up his first Uber passenger.

Dante, who lives out of the car, knew little about the turmoil in the upper echelons of his employer, 560km away in northern California.

“It is what it is,” he said. “I don’t really expect anything else from them.”

“It would be nice to make more money,” he added.

Yet, the most remarkable aspect of Uber’s calamitous staff meeting was not necessarily Bonderman’s misogynistic remark, or even the findings of the review led by the law firm of former US attorney general Eric Holder. It was a subject that was barely mentioned at the meeting: the increasingly frustrated and demoralized workforce of Uber drivers — some of whom, like Dante, have been rendered homeless.

To some labor activists, the major ethical failing that should be inspiring bold promises of change at Uber is not so much the treatment of its well-paid tech workers, but the plight of its impoverished drivers, who are earning low and unstable wages in a job without security or benefits, or struggling to pay off loans for their Uber cars — debts that some have equated to dodgy subprime mortgages.

Classified as contractors, the drivers have little recourse to deal with a litany of workplace challenges and hazards, including wage cuts by the company, harassment and sexual assault by passengers and a rating system that some have said is plagued by racial biases. It is well-known that Uber has done battle with labor organizing efforts and traditional taxi regulations in markets across the world.

However, what is only now starting to become more apparent is how Uber’s aggressive global expansion and alleged neglect of its workforce has left at least some of these workers with no option but to live in parking lots and on street corners — including in Los Angeles, one of Uber’s most successful cities, and the place where Kalanick was born.

In an e-mail to his staff this week, Kalanick said his departure was an opportunity to grieve the recent loss of his mother and work on “Travis 2.0.”

His leave follows a months-long onslaught of negative publicity over a long list of controversies and scandals.

It was an account of sexual harassment and discrimination from former Uber engineer Susan Fowler, published in February as an instantly viral blogpost, which finally prompted the company to commission Holder to launch an investigation into the company’s workplace culture. (The inquiry resulted in the termination of more than 20 employees and recommendations that Uber overhaul its human resources processes and leadership training.)

Like many Silicon Valley companies propelled by the personality of their founders, Uber’s culture seemed molded around that of its abrasive leader, who famously used the term “Boob-er” to encapsulate his desirability among women and bemoaned the fact that, as CEO, he could not sleep with any of his employees.

In March, he was caught on camera berating an Uber driver who raised with him the subject of declining wages and the profound financial struggles of drivers, prompting Kalanick to say: “Some people don’t like to take responsibility for their own shit.”

UBER ‘SLAVES’

Critics have argued that a dismissive attitude toward drivers is embedded in the company’s current business model, which is dependent on cheap labor. Yet, Uber’s recent public discussions of reform have barely broached the issue of its relationship with drivers, which is often tested when workers are put in vulnerable positions.

Casmir Patterson, 32, found early on in her Uber driving career that she preferred to work late nights, when the Los Angeles traffic was more tolerable and when she could provide rides to women looking for a safe way to get home. However, on June 13 last year, during her last ride of the night, three intoxicated men entered her vehicle in West Hollywood and she quickly sensed trouble.

One of her passengers sounded like he was going to vomit in her car. She pulled over and asked the trio to leave. They refused, and then dragged her into her backseat, where they started punching her.

“I thought I was going to die,” she told the Guardian.

The men eventually fled, but not before kicking the outside of her car and running off with her keys.

Patterson called the police and reported the incident to Uber in the hope that the company could track down her attackers and help her with medical bills. However, the criminal investigation went nowhere and Uber did little to support her, she said.

Los Angeles police did not respond to repeated inquiries.

A week before the incident, Patterson had signed a lease through Uber’s vehicle loan program, known as Xchange. She was required to pay weekly fees of about US$146. As a result, Patterson had no choice but to keep driving for Uber, despite suffering from post-traumatic stress stemming from the attack, as well as damaged vision in her right eye.

“I just felt like I was trapped, like I was an Uber slave,” she said, adding that she could barely drive enough hours to make the car payments.

Unable to keep up with her bills, she ended up living out of her leased Uber vehicle for about a month until, running out of options, she moved back home to Chicago, where she fell further into debt before her car was repossessed.

“It’s just been a domino effect,” she said. “It’s really ruined my life.”

An Uber spokesperson said in a statement to the Guardian that after Patterson reported the incident, the passenger who booked the ride was immediately blocked from the platform, and after further investigation was banned permanently.

“Uber does not tolerate any violence in our community and this incident was upsetting,” the spokesperson said.

Uber also said that it has recently launched a pilot program to give drivers the option of purchasing injury protection insurance.

Patterson is just one of several women driving for Uber who have come forward in recent months to share stories of assault and harassment. However, despite all of its promises of corporate reform, there appear to be few if any substantive changes that enhance the rights of victimized drivers.

That might be because Uber does not see its drivers as its future. Part of the company’s sky-high valuation stems from an assumption by investors that Uber will do away with its human workforce, and the company has invested hundreds of millions of US dollars in a bid to lead the race for self-driving car technology.

Even that effort has been mired in controversy, because Uber is locked in a costly lawsuit with Google’s parent corporation, Alphabet, which has accused Kalanick’s company of stealing its proprietary self-driving technology.

Uber recently fired the head of its autonomous car unit, Anthony Levandowski, a former Google engineer alleged to have stolen 14,000 internal documents from his former employer. (In response to requests to hand over documents, Levandowski has invoked his fifth amendment right against self-incrimination.)

Although the lawsuit and departure of Levandowski could hamper Uber’s development of its own technology, the company has continued testing autonomous cars with pilot projects in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Arizona and San Francisco, where Uber’s self-driving vehicles were caught driving through red lights and initially banned by regulators.

One senior Silicon Valley executive who Uber tried and failed to poach last year told the Guardian that his job interview left him with the impression the company had little regard for its current fleet of human workers.

The executive said he asked Uber chief product officer Jeff Holden about the company’s long-term viability given the discontent he had observed among its drivers, and was shocked at the reply.

“He said: ‘Well, we’re just going to replace them all with robots.’ It was quite chilling,” the executive said.

“There was zero human empathy,” the executive said of his impression during the recruitment process. “It was as if he was saying: ‘Duh. Who cares if they complain?’ That was the moment I thought, ‘I don’t want to work here.’”

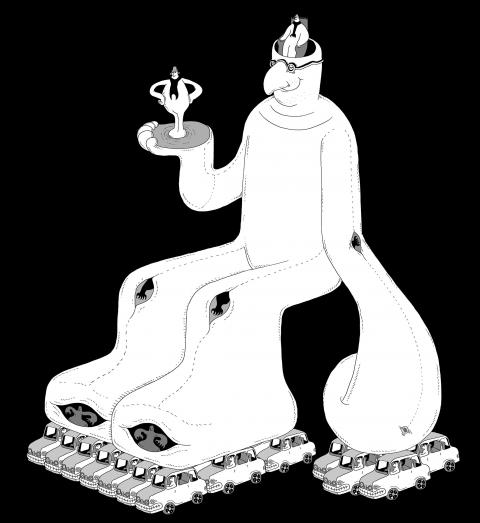

Uber views its human drivers as a stopgap, a prelude to a roboticized and thus far more profitable era. In the meantime, Uber appears to be adopting sophisticated psychological tricks to manipulate its drivers into acting with the kind of efficiency it would expect from machines.

The New York Times recently reported that Uber’s social scientists and data scientists have tried techniques from video games, such as incentivizing drivers to work longer hours with quirky — but worthless — digital achievement badges, even when it is not in their best interest.

Some male Uber managers even adopted female personas when communicating with drivers, because they found it boosted the response rate.

Meanwhile, the company has cut drivers’ wages and recently admitted to underpaying them by millions in New York City. Uber has also confessed to using smartphone sensors to monitor its drivers.

However, often lost in the debate is the poverty that can afflict Uber drivers, sometimes exacerbated by programs that the company created ostensibly to be of service to them.

Although there are no official statistics, there have been anecdotal cases documented across the US of Uber workers overnighting in their vehicles because they cannot afford to live where they drive.

Parking lots in Los Angeles reveal an even darker reality — drivers who have become homeless and live full-time in their cars. This is part of a larger trend. During this year’s count of homeless people in Los Angeles County, more than 2,000 cars were doubling as makeshift homes, a 50 percent increase from last year.

Often known for its meager public transport options and status as the capital of car culture, Los Angeles also holds the distinction of most Uber drivers in the nation — more than 20,000, 2015 statistics showed.

This is not because it is an especially remunerative place to drive. Los Angeles is known for its low fares and high cost of living. One 2015 estimate put Los Angeles drivers’ take-home pay per ride at almost US$2 below the national average, and drivers said Uber’s repeated readjustments and changes to the pricing system nationwide mean fares have only gone down since then.

“Sometimes it’s really bad, because after gas, it’s like, I literally make US$8 or US$9 an hour,” Dante said.

The minimum hourly wage in Los Angeles is US$10.50.

Before he started driving for Uber, Dante drove trucks. Like most of the homeless drivers who spoke with the Guardian, Dante asked not to use his full name because of the stigma associated with his situation, and also because of fears he could get into trouble with Uber.

Before taxes, he earns about US$1,200 per month driving for Uber and US$2,600 per month at another job, delivering medical cannabis products for a San Francisco-based company. However, the car Dante rents through Uber and Enterprise Rent-A-Car costs more than US$1,000 a month, including insurance.

That was the best deal he could get with so little cash on hand and a low credit score, he said.

His other major expenses — gas, a storage unit and a gym membership — come to about US$1,000, and he struggles with debt.

“I’m just going to stay in my car to save my money, so I can get into a better situation as fast as possible,” he said.

‘REWARDING EXPERIENCE’

Brandon, who has been driving more than a year for Uber and rival Lyft, said he usually parks in a different neighborhood every night. He sleeps in his back seat, concealed behind tinted windows.

“I don’t think people look into it too much,” he said. “But, you know, if they do, I’d have to advocate for myself, and I’d tell the truth, which is that, I’m an Uber and Lyft driver, I make less than minimum wage. My option is to sleep in my backseat, or to sleep on the street. Which would you prefer?”

The Guardian provided Uber with detailed questions about homeless drivers and their struggles with car payments and low wages. The company’s response was a two-sentence statement, released through a spokesperson.

“With Uber, people make their own decisions about when, where and how long to drive. We’re focused on making sure that driving with Uber is a rewarding experience, however you choose to work,” it said.

Uber, which reportedly has a very high turnover rate for drivers, has worked to find creative ways to attract enough drivers to support its rapid growth. That includes its Xchange leasing program, which offers short-term leases to drivers, taking payments directly out of their wages.

The leases are expensive and even predatory, according to experts quoted in a Bloomberg investigation, which suggested the agreements resemble subprime lending programs that target risky borrowers with poor credit.

“Families end up homeless, because they literally cannot make enough money to pay for their vehicles and to fulfill any of their basic living needs,” said Veena Dubal, an associate law professor at the University of California, Hastings, whose research has involved interviewing Uber drivers.

One case in point is Renee, a mother of three, who began driving for Uber in Los Angeles in May 2015. She rented her car through the ride-share company and said she initially felt upbeat about her prospects.

“But then, when things got slow...” she said.

When things got slow, Renee went on to explain, she started to feel the full bite of her rental fees and the additional US$0.16 per kilometer she owed if she ever drove more than 145km per day.

That was a problem. Renee had been living in Lancaster, California, a 225km round trip from Los Angeles, the place where she would find most business. Renee’s children moved in with family and friends in Lancaster, and Renee moved into her car.

“It ended up being like running up an escalator going down,” she said. “It was hell. It was horrible. It was uncomfortable, physically; mentally. It’s embarrassing; it was demoralizing.”

She kept driving back and forth between Lancaster and Los Angeles, racking up hundreds of dollars in excess mileage fees. One evening, it all caught up with her.

“I was working that night, and I’d stopped to drop my daughter off at the babysitter. And the repo man was outside, and he repossessed the car,” she said.

Eventually she was able to buy another one.

Just after 2am on a recent morning, Renee emerged from her car in a parking lot about 3km from Los Angeles International Airport, eyes heavy with sleep.

“Most of these people here are fronting,” she said, meaning they were hiding the fact that they slept in their cars.

She looked out at the lot, which is reserved for Uber and Lyft drivers, who colloquially refer to the parking zone as “Jenny lot” or the “pig pen.”

Most of the about 100 parking spots were taken. A handful of drivers stood around smoking and chatting. The rest were in their cars, most with the driver’s seat fully reclined.

“There’s no business right now,” said Renee, who used to stay overnight in the parking lot all the time when she was homeless, but now only does so when she is too tired to drive back to her mother’s house in Lancaster. “If you have a place to go, why are you going to sleep here?”

“Now I know what people mean by two paychecks away from the street,” she said. “You’re like, I’m a whisper away from being [homeless]. So you drive, and drive, and drive.”

About 6m away, Gordon Swan stood alone outside his car, a black Pontiac Grand Prix. He recounted the winding series of events that has led to him living in the car that he has driven for Uber for seven years — a greedy property management company upping his rent; a falling-out with his sister; the creeping realization that he could not afford US$75 per night for a hotel.

A single dad with two kids in their early twenties — “They’re the best thing I’ve ever done,” he said — Swan is hoping to find work as an animator, and there is a large monitor built into the passenger side of his car.

For the moment, his whole life is in the car he drives for Uber.

“Remember [former US president Franklin] Roosevelt, he said: ‘You have nothing to fear, but fear itself’? I have a similar saying: ‘You have nothing to be embarrassed about, but embarrassment itself.’”

Living in his car is not ideal, Swan said, but he is doing his best to stay optimistic about his life as a homeless Uber driver.

He smiled uncomfortably.

“But it’s not like I would go around advertising it,” he added.

Additional reporting by Olivia Solon

Congratulations to China’s working class — they have officially entered the “Livestock Feed 2.0” era. While others are still researching how to achieve healthy and balanced diets, China has already evolved to the point where it does not matter whether you are actually eating food, as long as you can swallow it. There is no need for cooking, chewing or making decisions — just tear open a package, add some hot water and in a short three minutes you have something that can keep you alive for at least another six hours. This is not science fiction — it is reality.

A foreign colleague of mine asked me recently, “What is a safe distance from potential People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Rocket Force’s (PLARF) Taiwan targets?” This article will answer this question and help people living in Taiwan have a deeper understanding of the threat. Why is it important to understand PLA/PLARF targeting strategy? According to RAND analysis, the PLA’s “systems destruction warfare” focuses on crippling an adversary’s operational system by targeting its networks, especially leadership, command and control (C2) nodes, sensors, and information hubs. Admiral Samuel Paparo, commander of US Indo-Pacific Command, noted in his 15 May 2025 Sedona Forum keynote speech that, as

In a world increasingly defined by unpredictability, two actors stand out as islands of stability: Europe and Taiwan. One, a sprawling union of democracies, but under immense pressure, grappling with a geopolitical reality it was not originally designed for. The other, a vibrant, resilient democracy thriving as a technological global leader, but living under a growing existential threat. In response to rising uncertainties, they are both seeking resilience and learning to better position themselves. It is now time they recognize each other not just as partners of convenience, but as strategic and indispensable lifelines. The US, long seen as the anchor

Kinmen County’s political geography is provocative in and of itself. A pair of islets running up abreast the Chinese mainland, just 20 minutes by ferry from the Chinese city of Xiamen, Kinmen remains under the Taiwanese government’s control, after China’s failed invasion attempt in 1949. The provocative nature of Kinmen’s existence, along with the Matsu Islands off the coast of China’s Fuzhou City, has led to no shortage of outrageous takes and analyses in foreign media either fearmongering of a Chinese invasion or using these accidents of history to somehow understand Taiwan. Every few months a foreign reporter goes to