It was just after 3am when the ticker at the bottom of the BBC’s results program revealed that the vote count stood at exactly 50-50. When the final tally came in, the “Outs” had prevailed over the “Ins” by a nose in the Brexit vote, but it is that image of a dead heat that still burns at the back of my retina.

The outcome of the British referendum on remaining part of the EU was not the most significant moment of the British political year. For this country, it was the most significant moment of the century. With the subsequent election of US president-elect Donald Trump, the Brexit vote has also been invested with a prophetic quality.

The shock was amplified because barely any of the politicians on either side had seen it coming. Former UK Independence Party leader Nigel Farage, who led the “Out” campaign, had popped up earlier to concede defeat. British Secretary of State for Justice Michael Gove had decided that it was going to be such a tedious night that he took himself off to bed and an aide had to wake him to tell him that his side had prevailed.

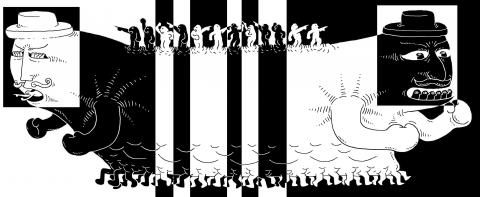

Illustration: Mountain People

Then-British prime minister David Cameron expected to be celebrating this Christmas in continued possession of the keys to No. 10 Downing Street. Then-British home secretary Theresa May heard about his resignation from the TV news.

If the outcome was stunning even to many who willed it, the details in the numbers were even more unsettling. They should trouble anyone, on either side of the argument, who cares about Britain. For they revealed a 50-50 nation.

In June, Britain made up its mind about Europe — and turned out to be in two of them. Britain was also making a choice about how it saw itself and its place in the world. However, there was no “we” about that either. On that deeper question, the people spoke with two voices. Britain was exposed as a country divided between the metropolitan and the provincial, the old and the young, the more affluent and those who have felt left behind, a Britain essentially comfortable with itself in the second decade of the 21st century and a Britain frustrated and discontented.

Six months on, that divide is as vivid as ever. There has been no catharsis, no healing. The losers remain sore, which is usual. Stranger is the behavior of the winners. If anything, some of them are even angrier with the world and swell in their paranoia that there is a conspiracy to steal the spoils of their victory.

The “Outers” press the argument that we must all bow before the demos and “respect the will of the British people.” To be fair, the “In” crowd would surely have said exactly the same had they prevailed. What was not resolved by the result, and continues to be a swirl of contention, is how you show “respect” to a referendum result that answered one big question, only to raise many more questions almost as large.

The conundrum is made all the more acute because the result was on such a knife-edge. If the government sought an outcome that aimed to represent the aggregate will of all those who voted, then it would try to negotiate a position that put Britain half in and half out of the EU. To respect the 52-48 margin by which “Leave” prevailed, it would aim to be just a little bit more out than in.

It is a stupendous, and underappreciated, irony that the task of extricating Britain from the EU without irretrievably damaging the economy and further shredding national cohesion has fallen on May.

Go back to the chronicles of the Tory civil wars in the years running up to the referendum. Read those horrible histories and you will struggle to find her name. In the ferocious battles that convulsed her party for decades, May was a non-combatant. She had been so mute on Europe that it was an unknown which way she would jump until shortly before the campaign started. This was true even among the small club of people with a genuine claim to call themselves a friend of May. They would express uncertainty about whether she was a closet “Leaver” or a reluctant “Remainer.”

Some believed that she would declare for “Out” because that would win credits within the Tory party and optimize her chances of getting to No. 10. As it turned out, she had an even smarter strategy, though it only looks like a cunning plan with the benefit of hindsight.

She took the “Remain” side, not least because she assumed that it would win. It was not a position that she held with any evident conviction. She surfaced only once during the campaign. Her speech in favor of continued membership was argued mainly on security grounds. It was regarded as so unhelpful for their cause by “Remainers” that people around Cameron wondered if she was working for the enemy. It certainly worked for her.

Cameron quit to spend more time with his grouse shoot. Kamikaze Gove made his suicidal dive onto the bridge of the “HMS Boris,” British Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs Boris Johnson. The invisible “Remainer” found herself in Downing Street. Even then, she was reluctant to embrace the task that time and chance had handed to her. As the full weight of the challenge began to descend on her shoulders, she tried to shrug off the burden. In her first speech from No. 10, she told the nation that she did not want her government to be defined by Brexit.

Her first half-year in office has been an education for the prime minister about the immensity of what faces her. What else have the past six months been about? Grammar schools? Oh, please. Brexit is the super-massive body dominating the political galaxy. Everything else is sucked into its irresistible gravitational field.

Sometimes it pulls her out of shape. The pressure to appease the hardline Brexiters bends a naturally cautious, pragmatic politician into something more demagogic and reckless. Her party conference speech, which alarmed moderate Tories, rattled business opinion and aggravated the EU leaders with whom she is going to negotiate, spoke as if the 48 percent did not exist. It is notable that her tone has since moderated.

More usually, she has erected walls of opacity around herself. The tautology of “Brexit means Brexit”; the cliche of “a red, white and blue Brexit.”

One explanation for her refusal to say what form of Brexit she will seek — this the explanation preferred by No. 10 — is that it would be foolish to expose her hand too early.

Another (this the explanation offered by many civil servants) is that her government is profoundly divided about what it hopes to achieve.

There is truth in both, but I add a third element of explanation. The prime minister understands that the negotiation will involve compromises and is not willing to face the furies that will unleash from hard “Brexiters” until it is strictly necessary. Because the “Brexiters” are the most noisy, it tends to get forgotten that May appointed a Cabinet with a “Remainer” majority. One reason she retrieved HMS Boris from the seabed and made him foreign secretary was that she had to have one prominent “Leaver” in a top job.

By far the largest Cabinet grouping is the “Pragmatics,” which includes both “Leavers” and “Remainers.” They know they have to deliver Brexit, but are rightly nervous about ending up with a disastrous version. To have a chance of success, there will need to be trade-offs. It will also need time.

British Permanent Representative to the EU Ivan Rogers has received a ritual roasting from the “Brextremist” press for warning that it could take up to 10 years to negotiate a new trading relationship. Rogers was being obedient to May’s injunction to officials that she does not want them to tell her what they think she wants to hear; she wants “the best possible advice.”

A decade sounds like a reasonable guess to me. To see why, join me on a short excursion to Greenland. The chilly island joined the EU as part of Denmark. Then, in the early 1980s, the Greenlanders decided they wanted out. That divorce took three years to negotiate and the main bone of contention was custody of fish.

If it took Greenland with a population of about 56,000 36 months to negotiate its divorce, a decade for Britain to reset its relationship with continental Europe sounds optimistic.

As the daunting scale of the task has sunk in at Whitehall, the concept of a “transitional” arrangement is gaining traction. There is growing talk about trying to broker bespoke deals on trade and immigration rules sector by sector, which would make complex negotiations even more intricate. A transitional arrangement is acquiring a nickname: “Smooth Brexit,” also known as “Smexit.” Or “Long Brexit” — “Lexit.” It is also attracting suspicion from the usual suspects that it is a “Remainer” scheme to defy the referendum result. Anything that falls short of the most “Brextremist” terms of withdrawal will be greeted with cries of betrayal of treachery from that quarter.

A long transition would leave Britain half in and half out of the EU. That would be devilishly difficult to negotiate, but it would not be inconsistent with the will of a people almost evenly divided by the referendum. A 50-50 deal is the sort of compromise that a pragmatic leader, who has always been essentially agnostic about Europe, would naturally be looking for. May probably intuits already that is where she will end up.

She just does not dare say so yet.

Congratulations to China’s working class — they have officially entered the “Livestock Feed 2.0” era. While others are still researching how to achieve healthy and balanced diets, China has already evolved to the point where it does not matter whether you are actually eating food, as long as you can swallow it. There is no need for cooking, chewing or making decisions — just tear open a package, add some hot water and in a short three minutes you have something that can keep you alive for at least another six hours. This is not science fiction — it is reality.

In a world increasingly defined by unpredictability, two actors stand out as islands of stability: Europe and Taiwan. One, a sprawling union of democracies, but under immense pressure, grappling with a geopolitical reality it was not originally designed for. The other, a vibrant, resilient democracy thriving as a technological global leader, but living under a growing existential threat. In response to rising uncertainties, they are both seeking resilience and learning to better position themselves. It is now time they recognize each other not just as partners of convenience, but as strategic and indispensable lifelines. The US, long seen as the anchor

Kinmen County’s political geography is provocative in and of itself. A pair of islets running up abreast the Chinese mainland, just 20 minutes by ferry from the Chinese city of Xiamen, Kinmen remains under the Taiwanese government’s control, after China’s failed invasion attempt in 1949. The provocative nature of Kinmen’s existence, along with the Matsu Islands off the coast of China’s Fuzhou City, has led to no shortage of outrageous takes and analyses in foreign media either fearmongering of a Chinese invasion or using these accidents of history to somehow understand Taiwan. Every few months a foreign reporter goes to

The war between Israel and Iran offers far-reaching strategic lessons, not only for the Middle East, but also for East Asia, particularly Taiwan. As tensions rise across both regions, the behavior of global powers, especially the US under the US President Donald Trump, signals how alliances, deterrence and rapid military mobilization could shape the outcomes of future conflicts. For Taiwan, facing increasing pressure and aggression from China, these lessons are both urgent and actionable. One of the most notable features of the Israel-Iran war was the prompt and decisive intervention of the US. Although the Trump administration is often portrayed as